Campaigns & Elections

How practical socialism helped India Walton win

Hard work and an emphasis on local issues means Buffalo could have its first female mayor.

India Walton Nate Peraccini

An upset victory by socialist India Walton over four-term Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown in the Democratic primary this week follows a familiar tale. An overly confident local power broker dismisses a lefty challenger as an amateur and takes reelection for granted. The underdog mobilizes local activists and captures the imagination of the rising political left. Brown, like others before him, tried to make up for lost time in the home stretch of the race, but Walton, a registered nurse and community activist, ended up 7 points ahead on election night. This story of incumbent arrogance, however, only explains so much about why she will become the first big-city socialist mayor in America in decades. “People are just ready for a change,” Walton said in an interview. “We have a message that resonates in a city like Buffalo, a blue-collar working-class city, (where) people are looking for a working-class hero, and that’s what I bring to the table.”

Walton does not run from the socialist label, but she does not lead with it either. Her campaign website does not even use the word to describe her policies, but it does have a lot of details about potential police reforms, stormwater management – and jobs. Buffalo will likely have its first female mayor because she worked hard, attracted support from established groups like the Working Families Party that had previously backed Brown, and focused on local issues rather than ideology. That is a significant difference between her and democratic socialists like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of the Bronx and Queens, who put that ideology front and center in building her political brand.

Buffalo was once a model for racial integration in the country, but those days are long gone. Its industrial base has eroded and while the local economy is recovering from the pandemic, unemployment remains a significant problem. This is especially the case in long-struggling places like the East Side, a predominantly Black neighborhood where residents have not shared in the wealth generated by rising rents and the big-ticket public investments in the private sector that Brown had touted alongside political allies, according to Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University at Buffalo. “It wasn’t a mixed pattern of development … and it was a development that gave the market full rein to run,” he said in an interview. “(The election) was a rejection of the neoliberal city that Byron Brown sought to build.” A spokesperson for Brown did not respond to a request for comment.

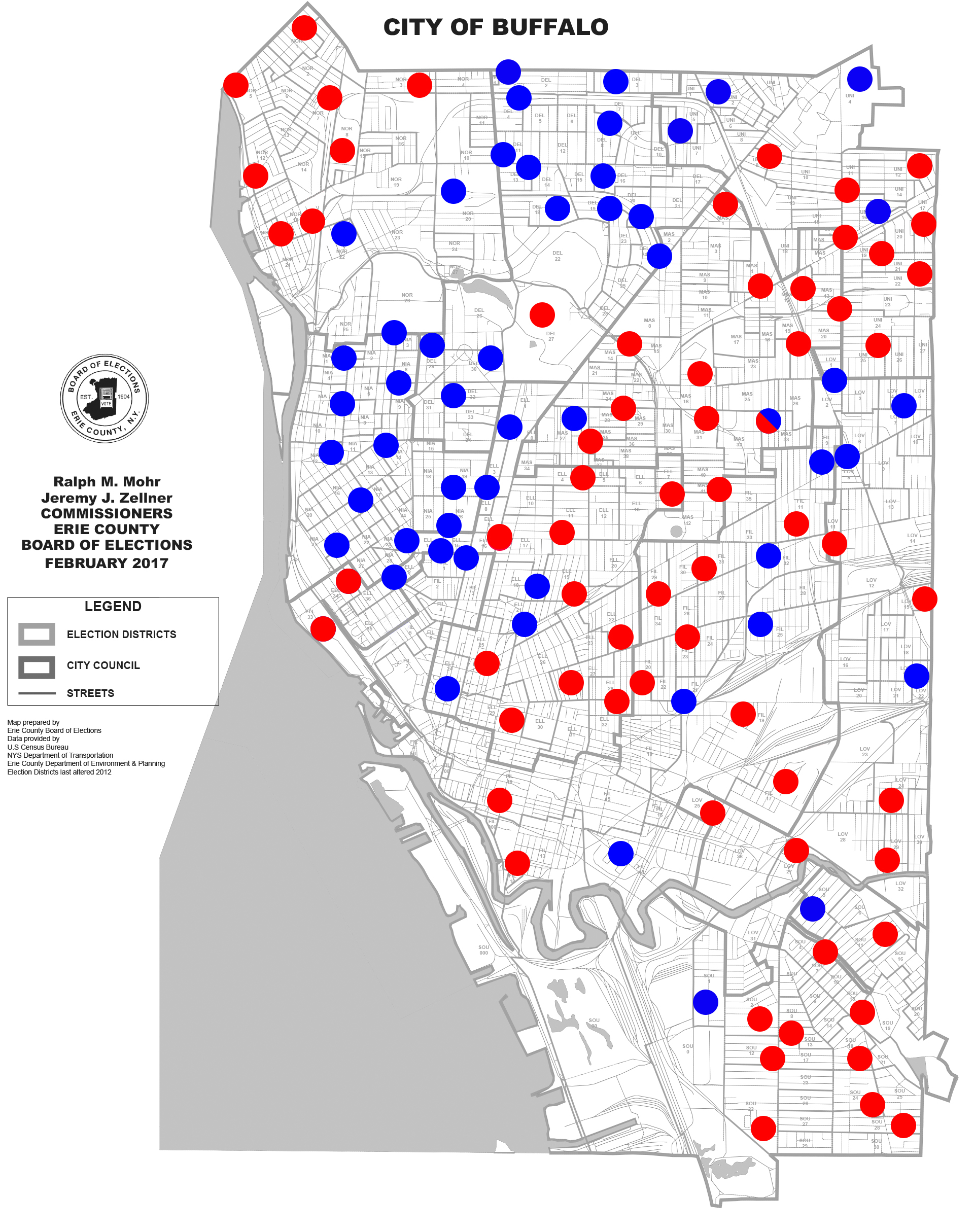

Socialist candidates of color have pulled off more than a few upsets in recent years, but there have been questions about how much they appeal to relatively wealthy, highly educated white lefties (white voters make up nearly half of Buffalo’s population) compared to the Black voters (who make up 36.5% of the city’s population) who disproportionately suffer from economic and racial inequality. “I don’t think we saw it play out that way at all,” said Clarence Lott, a former Brown supporter, longtime grassroots organizer and leader of the local community group East Side Political Network. A map of the Election Day results and early voting (absentee ballots have yet to be counted but have little chance of switching the primary outcome) showed that Brown – who like Walton, is Black – won a majority of the precincts in the East Side while also doing well in white areas like South Buffalo. Walton, however, did well enough in those areas to win an outright majority of all voters. She did especially well in racially mixed areas along the waterfront.

She credits the Working Families Party with providing the political know-how and resources to mobilize voters in an election where about 20% of voters turned out this year, which is well in line with past mayoral elections. “Everything from planning our media strategy and attracting national media, to our fundraising campaign, to our field game – you name it – the Working Families Party was very involved and super helpful to every single part of this campaign,” Walton said in an interview. “We could not have done it without them.” Another key source of support came from the union representing Buffalo’s teachers. Its thousands of members alone might have put Walton over the top in a race where she was ahead by less than 2,000 votes on Election Day. Like the WFP, they too used to support Brown, but this time around used their institutional influence to help a political outsider.

Her victory means less talk about Tesla as a savior for the downtrodden and more consideration for ideas backed by Walton like public banks and giving minority- and women-owned businesses more help getting government contracts. She is also vowing to end the school speed camera program that Brown defended as promoting public safety. It generated animosity in communities of color, according to Lott. “It was a money grab,” he said of the speed camera program. Brown had won previous reelections by comfortable margins, but he likely lost voters because of his response to Black Lives Matter protests last year when he defended the police department despite controversial incidents like two officers violently shoving an older man to the ground. “He didn’t read his base accurately at all,” Lott said. “He really didn’t.” Compare that to how Walton’s pragmatic socialism plays out on public safety. “Defunding police is not a thing,” she told The Buffalo News editorial board earlier this month. “It’s not an effective way to communicate with people.” She has talked about independent oversight of the police department and not having officers respond to people suffering mental health episodes.

Brown is reportedly considering a write-in candidacy for the November general election, but Erie County Democratic Chair Jeremy Zellner has already said the party is backing Walton this fall. Other political leaders are also getting behind her after not endorsing in the primary. “I’m eager to have a partner that will be responsive,” said Assembly Member Jonathan Rivera, who represents part of the city. “It’s not rocket science. The personal touch and (her) consistency of message was just going to win.”

Republicans meanwhile did not nominate anyone for mayor despite recent precedence for Republicans unexpectedly winning races in Democratic strongholds. Instead, Buffalonians are likely to get their first socialist mayor. “This is why you put up token opposition,” said Jacob Neiheisel, associate professor of political science at the University at Buffalo. “It’s because stuff like this happens.” Former GOP gubernatorial candidate Carl Paladino, who has said he is “not a racist” despite a history of controversial remarks, is reportedly considering a long shot write-in candidacy, though Neiheisel added the odds are firmly against any Republican prevailing in an overwhelmingly Democratic city.

With Walton winning the Democratic primary, the big question is what she might do with her future power to overcome resistance from influential local political interests. The city’s police union is already promising to fight her agenda. Real estate interests are waiting to see how threatening she will be to their bottom line. Wealthy donors – including Merryl Tisch, the wife of Loews Corp. President and CEO James Tisch – had donated thousands of dollars to Brown in recent weeks. They can now spend money on other causes, which may or may not include funneling money to thwart Walton’s political agenda. While Walton has seemingly made the politically impossible happen, she is not aiming to surprise anyone once in office. After running for mayor in plain sight, others may have to catch up to the pace of change she wants to bring to Buffalo. “Not everything is going to happen the way we want, when we want, but I’m not going to mislead people,” she said. “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

NEXT STORY: Races to watch for potential come-from-behind victories