Politics

If Not Common Core, Then What?

Lorri Gumanow was furious. Her 13-year-old son, who had always thrived in the classroom, was suddenly struggling. Like thousands of public school students across New York, he had recently failed a new, more rigorous mathematics test tied to the state’s revamped education standards. Gumanow’s son, who began to have meltdowns over his homework on a regular basis, had even threatened to kill himself, she said.

At a packed Manhattan auditorium this past December, Gumanow joined hundreds of other parents and teachers gathered to express their anger and frustration over the state’s Common Core education standards, which they blamed for the widespread decline in test scores. The flawed rollout, they said, had left teachers, parents and students woefully unprepared. As state Education Commissioner John King sat stoically on stage, Gumanow said that the only response from school officials was to tell students they needed to try harder.

“Unfortunately, when you throw some kids into the deep end of the pool, with a brick tied to their ankle— label the brick whatever difference you prefer—it is foolish to believe they are all going to be able to come back up for air. A lot of them are going down!” said Gumanow, a former special education teacher. “I am tired of the jargon and the rhetoric. You are willing to write my son off as collateral damage.”

Parents who, like Gumanow, have voiced confusion about the Common Core standards and uncertainty as to what the criteria mean for their children, are not alone in their criticism. School districts have said they were not provided enough guidance to properly comply with the new standards, and educators, many of whom object to the new teacher evaluations tied to Common Core-aligned testing, have said they felt unprepared. Politicians have been quick to pounce, with state senators and members of the Assembly sponsoring bills requiring a moratorium or even a full repeal.

Even Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Merryl Tisch, the chancellor of the state Board of Regents, both strong proponents of Common Core, have acknowledged problems with the way it was implemented. During his budget address this year, Cuomo said that there has been “too much uncertainty, confusion and anxiety.” Tisch told City & State that the rollout was “uneven” and that the Board of Regents should have done a better job engaging with parents.

By early July, Westchester County Executive Rob Astorino, the Republican gubernatorial nominee, had seized on the controversy. At a press conference announcing a new “Stop Common Core” ballot line, he assailed the standards as a “disaster” and promised to repeal them if elected. The standards, he said later, are “dumbing down students.”

Yet as the attacks and criticism have reached a fever pitch over the past year, one part of the equation always seems to be missing: What would replace Common Core if opponents actually succeeded in getting rid of the controversial plan?

The evolution of education policy, in New York and nationwide, has been building up to this boiling point for over a decade.

When the U.S. Congress reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 2001, more commonly known as No Child Left Behind, it required states for the first time to set a learning standard that specified what students in grades 3–8 and high school should know. It also mandated the use of standardized testing to measure student proficiency in those grades, though each state was free to set its own minimum standards.

In 2008 New York began to re-examine its own standards, and created a work group to develop new ones. While that process was under way, the federal government gave states the option of adopting a new set of standards known as Common Core, which was developed by the Republican-led National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, along with other education groups and teacher work groups. These standards built on No Child Left Behind, while also aiming to set a higher bar and create a single national standard.

Then, in 2009, President Barack Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which included $4.35 billion for his federal Race to the Top initiative. If states agreed to certain education policy requirements such as implementing higher standards intended to make students more college- and career-ready and instituting annual professional performance reviews for teachers and principals, they could receive a share of the money.

A year later, in 2010, New York adopted Common Core. According to the state Department of Education, New York has spent $413.5 million in Race to the Top funding and has $283.1 million remaining. Implementation began in the 2011–12 school year. By spring parents and teachers were already raising concerns about the rushed implementation, among other objections.

The first round of Common Corealigned tests was taken in the spring of 2013. When the results were released last August, the uproar reached its peak. Across the board there had been a sharp drop in scores—a drop that was anticipated by the state Department of Education, but jarring to parents and students. Only 31 percent of students in grades 3–8 passed the new exams in both reading and math, compared with 55 percent in reading and 65 percent in math the previous year on the old tests.

This year, after Cuomo called for “corrective action,” lawmakers approved legislation that delays the use of students’ performance on Common Core tests as a criterion for grade placement and as a factor in teacher evaluations for teachers rated “ineffective” or “developing.” Students will still take the tests, but the scores will not affect grade placement or whether a student graduates until 2022. Teachers received a two-year postponement before their students’ performance on the test counts toward their own evaluations.

Although he has been critical of its implementation, Cuomo has been a staunch advocate of the Common Core standards and also integral to bringing millions of dollars in Race to the Top funding to New York. It appears highly unlikely that Cuomo would allow the standards to be scrapped, and the possibility of the state Legislature passing a repeal is equally doubtful.

Of course, shifting political winds could change the current landscape, with or without a new governor. The next round of Common Core scores are expected to be released this month. Several education experts said that if there is no sign of improvement, the calls to get rid of the standards would only get louder.

In early July, Rob Astorino, flanked by a few parents holding anti–Common Core and pro- Astorino signs in the pressroom of the Legislative Office Building in Albany, unveiled his “Stop Common Core” ballot line. After making a relatively brief announcement, Astorino spent about 20 minutes deflecting questions about the specific details of his education agenda. Instead he repeatedly insisted that he has the support of parents and teachers from around the state and that he was leading a “grassroots” movement.

“Obviously Cuomo’s Common Core has been a disaster. The rollout and implementation speak for themselves on how bad it’s been,” Astorino said. “But even once the implementation is rolled out some years in the future, we’re still left with Common Core, which I oppose, and it’s something we should get out of, and I will get out of when I become governor next year.”

All three Republican candidates running for statewide office, including Astorino, nominee for attorney general John Cahill and nominee for state comptroller Bob Antonacci have joined the “Stop Common Core” ballot line initiative. Cahill originally said he supported Common Core, but switched his position when the line was launched. At least one state Senate candidate, Sue Serino, has also signed on.

Assemblyman Ed Ra, a member of the Republican minority, co-sponsored a bill during the past legislative session that would fully repeal Common Core. He also introduced a bill that would put the standards on hold while the state convened an independent blueribbon commission of educators to examine them.

“I would prefer either of [the bills were passed] if we could get them passed,” said Ra, who admits that there is little chance either will. “I support both bills, but the idea of my bill was we’d basically put the brakes on what we’re doing and basically put together a panel of educators to study, to come together and look at the standards and decide: ‘Are these the standards we should move forward with, [or] should we move forward with another set of standards?’ ”

If the moratorium were successful, Ra said that local school boards and superintendents could reform their existing curricula, move forward with Common Core or revert to the previous standards.

Republican State Sen. Greg Ball, who declined to run for re-election this cycle, has introduced legislation to repeal Common Core in the other house of the Legislature, where, unlike Ra, he is in the majority conference. Ball’s bill is only about 140 words long and would require the state to immediately discontinue implementation of the Common Core standards and opt out of federal Race to the Top funding. It does not specify what steps the state should take afterward.

The push by politicians to repeal and replace the standards is one potential resolution to the controversy over Common Core, but it also raises a number of questions. No politician has yet introduced a comprehensive plan that addresses all the ramifications of repealing Common Core. Instead they have focused on getting the word out that Common Core is bad for America.

“The requirement of the Common Core that Astorino and others say they’re going to repeal is a multiheaded beast, and they’re going to have to cut off all the heads,” said David Bloomfield, a professor of Educational Leadership, Law and Policy at the CUNY Grad Center and Brooklyn College. “They would have to renegotiate the No Child Left Behind waiver, they would have to change the testing contracts and they would have to change the teacher evaluation system—and that becomes a very tall order. And at some level it’s actually not necessary. But at some level people would begin to question, as they already are, ‘Well, what are you going to replace it with?’ ”

New York State United Teachers President Karen Magee said her union supports the Common Core standards, though it has been critical of their implementation and the teacher evaluations that were introduced in concert with them. A former teacher, Magee said there has always been a clearly articulated state syllabus that guided local school districts in developing their own curricula.

“If they were to repeal the entire Common Core, they would have to develop some kind of common thread, at least throughout the state,” Magee said. “There has to be something, because in the absence of any structure you have complete chaos.”

Moreover, despite the claim made by many Common Core opponents that the state is forcing curricula on districts and teachers, Chancellor Tisch said that local school boards do in fact retain control.

“It is one thing to set standards; it’s another to impose how districts do their instruction and choose their curriculum,” Tisch said. “I think once you set a standard—how teachers do that, how superintendents choose curriculum along with teachers and principals—that is totally locally determined, and I will fight for the right of every school district to make those decisions. But we would be doing a disservice to our students, a real disservice, not to have benchmarks of performance of what kids need to measure at what grades, in order to provide a road map.”

That distinction between standards and curriculum, which is often muddled in public debate, is also at the root of the controversy, experts say. Is Common Core all about testing? Curriculum? Standards? All of the above?

In an interview with City & State, Astorino insisted that the standards and curriculum have basically become the same thing, since “the curriculum is designed to meet the standards of the test.” While there is a clear link between standards and curriculum, however, experts say conflating the two can be misleading.

“[Standards are] a framework around which you build a curriculum,” said John Ewing, the president of Math for America, a private nonprofit organization with a mission to improve math education in secondary public schools. “It’s the curriculum that’s rigorous, it’s not the standards that are rigorous, and it’s sort of a misunderstanding about what standards are all about. So it always makes me nervous when I hear people talk about some set of standards, or ‘Our standards before were much better before than this new set of standards.’ ”

A number of experts also said that Common Core has become a scapegoat for a variety of problems and issues within the education system that may only be loosely tied to the new standards.

Lana Ajemian, the president of the New York State PTA, said that growing concerns about standardized testing have been unfairly linked to Common Core. “We believe many parents have a hard time separating those issues from the intent of the Common Core, which is basically to raise standards and ensure our kids are college- and career-ready,” she said.

Another widespread misunderstanding may stem from a key distinction between the Common Core standards and No Child Left Behind. No Child Left Behind tracked high school graduation rates but not what students had learned when they graduated, said David Albert, director of communications and research from the New York State School Boards Association. Common Core focuses on what students should know in each grade.

“What they do is they basically say, ‘These are the kinds of things students at each grade level should know in various subject matters.’ Now, that does not tell the instructor or the teacher how he or she has to go about teaching that particular standard,” Albert said. “A curriculum is a specific set of materials or subject matter that a teacher would use in order to instruct students in a particular topic. It’s really up to the individual teacher to determine how he or she wants to instruct students to meet the standards. So it’s kind of like setting a goal and saying, ‘Okay, we don’t care how you meet this goal—just meet it.’ And how you meet it is the curriculum.”

Another question that has been largely ignored by foes of Common Core is what would happen to the flow of federal education dollars to New York if the program were scrapped.

In 2010 states were given the option of applying for a waiver that enables them to have greater latitude in deviating from No Child Left Behind requirements as long as they adopt standards that adequately prepare students for college or the workforce. Though most states went with Common Core, one state—Virginia— elected to go for standards approved by postsecondary institutions.

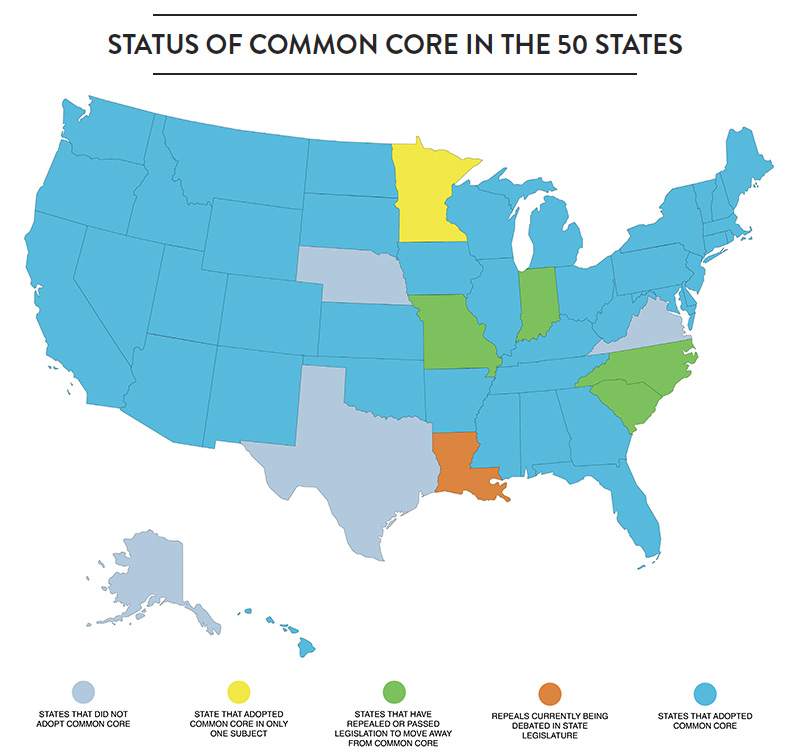

Since March at least six states have opted out of Common Core, or tweaked the standards, and Louisiana and Wisconsin are debating moving away from Common Core in their state legislatures.

Earlier this year Indiana became the first state to repeal Common Core, and the U.S. Department of Education sent state officials a letter reminding them they had to submit an amended No Child Left Behind waiver within 60 days or risk losing federal funding. The state approved a new set of standards by the deadline, although critics say it differs little from Common Core.

In April Washington became the first state to have its No Child Left Behind waiver revoked by the federal government, largely because Washington did not require state test scores to be integrated into teacher evaluations. When a state has its waiver revoked, districts lose control of millions in federal money, because schools have to begin setting aside money for federal remedies for low-performing schools, such as tutoring and school choice.

Other states, including Missouri, North Carolina and South Carolina, recently passed legislation to move away from Common Core. None of those three states explicitly prohibit its use, and each will continue to use the standards through at least the 2014–15 school year while they develop new standards.

Oklahoma also repealed Common Core this spring and reverted to its previous state standards, but the state has twice delayed approving an official transition plan. Astorino has suggested taking a similar course of action and at the same time salvaging New York’s so-called “lost standards,” which were in the works but abandoned in favor of Common Core.

Walter Sullivan, an associate professor of Educational Leadership at the College of New Rochelle who spearheaded the “lost standards,” estimated that finishing the work would take about one year per subject. Sullivan said that creating comprehensive standards would take time to “do it right.”

Tisch argued that any further delay would be counterproductive, pointing to national and international test scores that show the United States lagging behind other countries. “Simply to stand still while the rest of the world is moving forward, to me, is just a ludicrous argument,” she said. “And if Rob Astorino is saying that he is against Common Core, then I would suggest very strongly to him that he absolutely understand what is going on with NAEP [National Assessment of Educational Progress] scores, with PISA [Program for International Student Assessment] scores, and then come back and tell me that we shouldn’t be raising standards.”

Even though many experts agree that sticking with Common Core is the best course of action, most of them point out that the standards themselves are not without their weaknesses.

One of the most pressing concerns is how special needs students and English Language learner students are handling the new standards. Another concern is that some of the standards in the lower grades may be too sophisticated—for teachers as well as students. Elementary school teachers, as generalists who have to teach multiple subjects, may not have all the skills needed to teach everything the new standards demand. Some also worry that the standards will not be flexible enough to address such concerns.

“There hasn’t been a lot of work with that, so elementary school teachers will struggle for a little while trying to make this work. Not all of them—some of them will be great— but many of them will have to struggle for a while,” Ewing said. “As they rolled out the standards, they probably should have worked harder at dealing with that problem.”

Another criticism is that teachers are forced to pace their lessons according to the standards rather than to the point of mastery.

But NYS PTA President Ajemian said the idea of Common Core is to move away from just regurgitating facts toward understanding how to use those facts.

“Our kids are going to be competing in a very different world, and facts will be very accessible, because there’s so much between the Internet and everything else,” Ajemian said. “How to be creative and innovative and how to apply those facts is going to be very important to how successful they can be competing in a global workplace. They’re not just competing with their neighbor next door.”

So where does this leave the future of the Common Core standards in New York?

CUNY’s David Bloomfield called the Common Core adjustments made during this past legislative session “important and surprising victories,” given the strong support for Common Core by the governor and the state Department of Education.

“It’s kind of an interesting political waiting game going on,” Bloomfield said. “There’s still going to be testing, but they delayed the consequences. [Cuomo and the state Department of Education] think the opposition will either die down or simply be distracted over the next two years so they can kind of roll it out again without anybody paying attention, without the current outcry that we have now. The opposition is hoping that Tisch and [the Board of Education] will move on.”

Ajemian said that the public debate in New York has subsided in recent months, although it could flare up again soon.

“Actually, it’s pretty quiet [in New York] right now,” Ajemian said about public calls for a repeal. “We’re anticipating as the scores are released—well, we’re not sure what to anticipate—but we imagine we will be hearing more once the scores are released.”

Given Cuomo’s commitment to Common Core, a lot also depends on the elections coming up this fall. Astorino is trailing badly in the polls and in fundraising, and political observers question whether his new Stop Common Core line will be of much help.

“A lot of legislators are up for election; the governor is up for election,” Ra said. “It’s going to be an issue in the governor’s election, it’s going to be an issue in the state Legislature elections, it’s going to be an issue in every congressional election … it’s going to be an issue all over the country. Really, it’s hard to say [what will happen], not knowing who those players are going to be from the get-go.”

One common theme among education officials and experts has been dismay at how the debate over Common Core has been used for political ends. Regardless of whether the standards are repealed, politicians will continue to hijack controversial education issues to score political points, they lament.

“I think, quite honestly, the merger of rollouts of the standards while simultaneously trying to develop an evaluation system in the state, that caused a lot of unrest,” Tisch said. “Now, if you would like to say that perhaps the implementation was uneven—I will take that criticism. If you want to say we didn’t engage with parents along the way, I would say ‘absolutely.’ But it simply never dawned on me that when we spoke about raising standards and making standards more compatible with what students would need in the 21st century that it would become a political quagmire.”

The political and legal complexities surrounding Common Core are not lost on Astorino, who has since walked back his absolute opposition to the standards.

When pressed, Astorino conceded that he would be open to tinkering with them instead of ditching them altogether, given the drawbacks of starting the process all over again.

“It is certainly being considered,” he said. “You know, if the foundation is broken, do you just continue to build, or do you rebuild the foundation so it’s steady? So I think everything has to be on the table for this.”

NEXT STORY: Urgent Care: $8 Billion Medicaid Waiver Driving Reinvention Of Brooklyn's Hospitals