Education

Remote teaching is hard. Will teachers get paid accordingly?

Unions want to make sure teachers’ extra time and effort isn’t forgotten.

After New York schools closed due to COVID-19 the United Federation of Teachers had just a week to negotiate fair working conditions for its members who would now be working from home. Anna Fedorova_it/Shutterstock

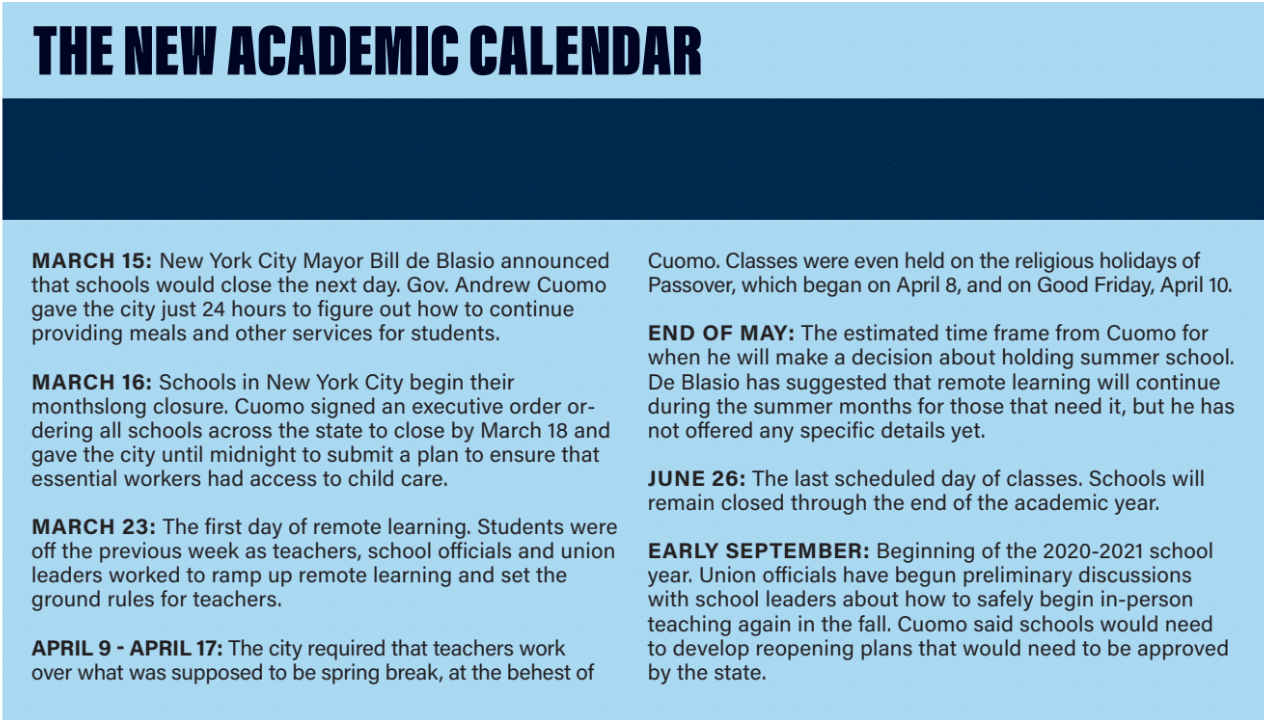

When the coronavirus pandemic forced Gov. Andrew Cuomo to close schools across the state in mid-March, teachers found themselves in a totally unprecedented situation. In just a matter of days, schooling needed to shift to an entirely remote model, upending the traditional school day and lesson plans. In both the switch to online learning and planning to reopen schools in the fall, unions have been at the forefront to ensure teachers don’t get mistreated while many of them are going far beyond traditional expectations.

Although a handful of counties and individual school districts had already announced closures before Cuomo signed an executive order on March 16 ordering all schools across the state to shut down by March 18, the switch to remote learning needed to happen swiftly. In New York City, the district had just one week to figure out what online learning would look like, both for students and for teachers.

This also meant that in just the course of a week, the United Federation of Teachers had to negotiate fair working conditions for its members who would now be working from home. Their contract, meticulously crafted, was designed for the traditional classroom. So the union and the district quickly came to agreements over best practices to ensure that demands on teachers and other staffers like guidance counselors were not unreasonable. “It’s been a challenge,” United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said. “There was no plan in place to do any of this. We don’t have anything in our contract that covers something like remote learning.”

“Look, under the emergency orders … they can force us to work, but they can’t force us to work for free.” – United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew

The biggest change came in the form of an expedited grievance process, condensing what could normally take months into only about a week. Given the unusual circumstances educators found themselves in, coming to a faster resolution on issues that may arise with a new system of teaching took precedent. Mulgrew said that about 50 complaints have been filed under the new system, many simply the result of minor miscommunications and otherwise working out kinks in a system that required a quick learning curve. At the beginning, for example, some people were attempting to recreate a traditional school day, even though it was clear such a method would never work. “It’s been about a balance of trying to make sure that we won’t allow anyone to be taken advantage of,” Mulgrew said. “But also at the same time, understanding that this is uncharted territory, and teachers will always go above and beyond.”

The same conversations were happening across the state, according to New York State United Teachers President Andrew Pallotta. Although the specifics of what students and teachers needed to ensure continued education during the pandemic varied slightly by region, districts and local union chapters quickly stepped up to figure it out. “What I got from our local presidents from around the state was that there was a lot of cooperation,” Pallotta said. “And just like in any negotiation, there’s a give and a take, and what makes sense.” He gave as a somewhat extreme example that just because teachers were working from home, it would be unacceptable for districts to schedule remote meetings late at night.

The issue also arose of teachers working at times they were not meant to without extra compensation. Perhaps the most controversial example was that school districts, including New York City, mandated that teachers work through spring break as well as on two religious holidays, on the word of the governor. Mulgrew said he and his members understood working on the five days after Easter given the circumstances, but took issue with being forced to work on the first full day of Passover and Good Friday, both major religious observances. Mulgrew said his union negotiated a package that prevented anyone who took off those days from being penalized, but still plans to get full compensation for the seven additional work days that teachers were supposed to have off. “Look, under the emergency orders … they can force us to work, but they can’t force us to work for free,” Mulgrew said.

Similar issues may arise over the summer if school districts decide to continue with classes. Although Cuomo has ordered schools to remain closed for the rest of the school year, the structure of summer school remains something that still needs to be worked out. Cuomo said decisions about that will come at the end of May.

In Buffalo, for example, some districts are considering enhanced summer school programs. “I would think it would be wrong to mandate that teachers have to teach summer school because some of them have other jobs that they have to do,” Buffalo Teachers Federation President Phil Rumore told Spectrum News. He added that he expected plenty of teachers would volunteer nonetheless, but the situation would likely necessitate a compensation package for teachers. Pallotta said he supports voluntary summer school programming with local control over what that may look like, including the potential for limited in-person learning.

With cash-strapped districts facing massive state and local cuts to funding, it’s unclear where the extra pay might come from. Already, many districts are warning of staff cuts if they lose funding, which Cuomo has said is possible absent additional federal aid. Pallotta said that his union will be involved in any potential cuts to ensure they don’t come in places that directly impact the day-to-day teaching of children. But he said schools have long been underfunded, which is why the union had been calling for a new tax on millionaires and billionaires before the coronavirus crisis. He said that the union will continue to advocate for that tax now to avoid cuts, even though the governor has resisted calls for new revenue sources. “We will fight these (layoffs) tooth and nail because you can’t move this state forward if you’re going to eliminate educators,” Pallotta said.

In addition to new state taxes, Pallotta said New York State United Teachers is also putting pressure on federal leaders to get additional funding in an upcoming aid package. He said he and other union leaders have been “working closely” with both U.S. Sens. Charles Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand.

The next big step will come when schools are scheduled to reopen in the fall. Cuomo has ordered schools and districts to begin formulating plans for reopening. Mulgrew said that in New York City, negotiations between the union and school leaders are still very preliminary. He has been vocal about schools ensuring the safety of both teachers and students, including implementing adequate social distancing in classrooms and adding robust COVID-19 testing infrastructure at schools. “If people make decisions based on politics versus safety – which I don’t believe we’re going to have – then we’re going to fight them,” Mulgrew said. “Straight up, it’s just going to be a fight.”

NEXT STORY: NY’s efforts to find COVID-19 treatments