Fighting fair: De Blasio, Council pursue conflicting plans to distribute homeless shelters

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office

At the heart of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to curtail the homelessness crisis lies the belief that every New York City neighborhood should be doing its fair share by providing enough shelter space to take care of its own.

During a Feb. 28 speech sketching out in greater details how he plans to improve and restructure the homeless shelter system, de Blasio argued it was fair to place shelters in communities based on how many people are becoming homeless in that area.

But his use of the term “fair share” diverges from its longstanding reference to a formal process aimed at placing city services, amenities and facilities – trash pickup, parks, homeless shelters, jails – by evenly distributing them based more on geography and population size.

And de Blasio cannot expect to redefine the phrase “fair share” without a fight.

A day before de Blasio gave his address and released a formal policy plan, the New York City Council published a reportconcluding that the fair share framework developed in 1989 had grown irrelevant. Several mayoral administrations failed to publicly release required analyses showing whether specific planning decisions were deemed fair or not, and agencies faced no consequences for failing to comply with the framework.

In fact, some areas known to have a high per-person rate of residential beds – which includes those found in jails, nursing homes, foster care facilities, inpatient treatment programs and homeless shelters – have seen this concentration intensify since the fair share criteria was adopted, according to the Council report.

The day after de Blasio’s speech, city lawmakers introduced a legislative package aimed at strengthening the fair share framework.One measure would, in most cases, prevent the city from opening a facility – such as foster care centers, nursing homes, or jails – in the top 10 percent of community districts most saturated with them. The provision could prevent de Blasio from opening homeless shelters in neighborhoods with a disproportionately high share of the shelter population, but where poverty or gentrification are forcing large numbers of residents into the shelter system. It is unclear how many communities could fall into this category. Regardless, the proposal appears likely to pit the City Council against the mayor and homeless advocacy groups, who say the city should prioritize keeping families entering the shelter system close to their old homes, schools, job sites, churches and support systems.

During his speech, de Blasio said that by the end of 2023 he would move people out of 360 apartment and commercial hotel locations, which tend to be costly and in poor physical condition. At the same time, his plan calls for creating 90 new shelters during the next five years while expanding 30 existing ones over seven years. De Blasio said the city realistically can reduce the roughly 60,000 homeless shelter census by only 2,500 over the next five years, which could raise the vacancy rate in the shelter system to 3 percent. With the new space, administration officials said they would have the flexibility to place families closer to where they previously lived, with the ultimate goal of having each of the 59 community districts house all of those who lost homes within its boundaries.

“We know a lot of people are going to say, ‘Wait, we don’t want anything like that in our neighborhood,’” de Blasio said. “Well, guess what? Everyone needs to take on their fair share. … We can figure out what will make it succeed and what will make it not a negative for the community, but … sometimes, even a positive for the community, especially because people will know the folks inside those doors come from right around their own streets, their own neighborhood, their own block.”

Asked by City & State about the fair share bills after the mayor’s remarks, New York City Commissioner of Social Services Steven Banks said the administration would review the measures. He noted while speaking to reporters that City Hall did not need lawmakers’ consent to open or expand a shelter, but he said the Council has a responsibility to oversee the Department of Homeless Services and to approve funding for it in the budget.

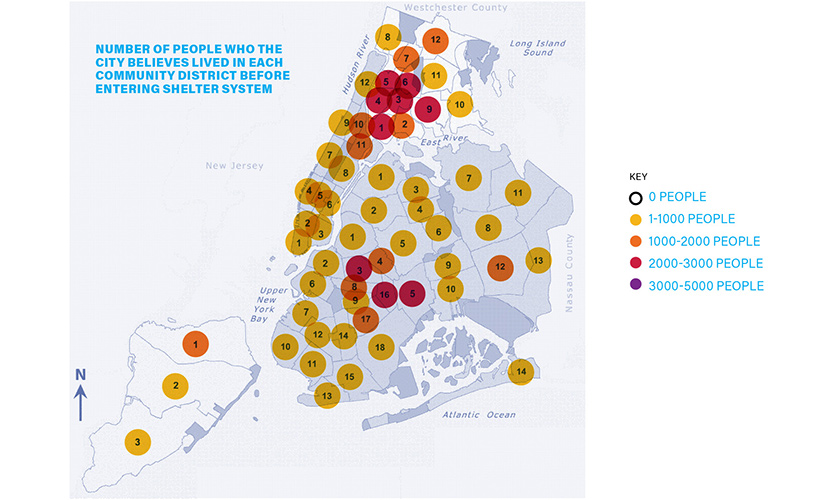

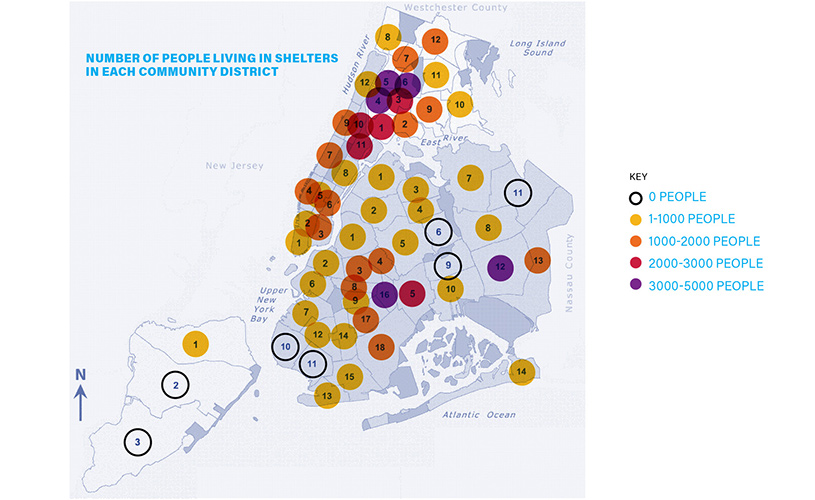

Mayor Bill de Blasio wants to eventually distribute homeless shelters so each community district has the space to provide shelter for all of its inhabitants who lose their homes. The first map breaks down the citywide homeless shelter population to show roughly how many people are believed to have last lived in each community district before becoming homeless; this provides a rough sketch of the shelter system de Blasio envisions. The second map depicts the current distribution of the shelter system, showing how many people are now living in shelters in each community district.

NOTE: The information comes from the city Department of Homeless Services’ Oct. 12, 2016 census. When trying to gauge where people entering the shelter system previously lived, the city attempts to find their last known address by looking at temporary housing applications or recent addresses associated with cash assistance, Medicaid and food stamp receipts. The data does not include people for whom the city was not able to identify a last known address.

City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito said lawmakers had questions they needed answered before they could vote for a budget that would once again increase spending on services for the homeless. Describing reform of the fair share paradigm as a priority, Mark-Viverito said she wanted to know more about areas where the administration believes it may open some of the 90 new shelters and how these sites were identified before assessing whether the administration’s strategy seems fair.

City Councilman Brad Lander argued that the fair share criteria has been virtually meaningless when it comes to homeless shelters. He told City & State this was due to the city opening almost all new shelters under emergency contracts, which do not require the city to conduct the fair share analyses. As part of the City Council’s eight-bill legislative package, Lander is sponsoring a measure that would limit this loophole by prohibiting the government from placing any facility, including those authorized by an emergency contract, in the 10 percent of community districts where such establishments are most concentrated. The city could override this provision if it proved the area truly needed a proposed facility. Lander said he did see a conflict in the effort to curb the concentration of homeless shelters in low-income communities of color and the mayor’s goal of uprooting homeless New Yorkers as little as possible.

“It is very clear to me that we can actually do better at both of them: that there is room to make sure that a family that wants to stay close to where they are … can do so, while also achieving fairer sitings,” Lander said, pointing to the example of a shelter run by the nonprofit CAMBA in his district that does not house many people previously from Park Slope. “It’s near transit, it’s near Prospect Park, it’s kind of reasonably close to jobs, it’s near CAMBA’s other services. It’s a good location, and we should look for more locations like that.”

It is difficult to assess how the mayor’s moves would alter the distribution of homeless shelters, given that its effects will likely differ from one community to another. For example, Brooklyn Community District 5 in East New York has 2,184 people in its shelters, while the area had a greater number – 2,846 – of people in the citywide shelter system whose last known addresses were in the community district. Adding more shelter space in East New York could help keep people in their own community, but it would also further concentrate homeless people in a community district that already has the ninth largest shelter population.

On the other hand, Bronx Community District 4, spanning Highbridge, Mount Eden and Concourse Village, has the largest shelter population – 4,833 individuals – but only about 2,690 people in shelters citywide last resided in the area. Under de Blasio’s plan, Bronx Community District 4’s shelter capacity could even be reduced somewhat and still have enough space to house its own residents.

In Queens Community District 12, which includes several southeast Queens communities near John F. Kennedy Airport where the city has rented hotel rooms for homeless people, the area’s City Council members seemed to disagree on whether the mayor’s vision would compete with the aims of the Council’s proposed fair share reforms. Councilman I. Daneek Miller said he believed the administration and Council could move toward their goals together. “If this (the mayor’s vision) is a fair way to deliver services in an equitable way … then (the legislation) will have no problem being passed and coming into law,” Miller said.

City Councilman Ruben Wills, who also represents the district, questioned de Blasio’s approach. He saidthose in shelters are overwhelmingly poor and people of color, and that the strategy de Blasio laid out would continue to saddle already struggling communities with additional shelters and obstacles to accessing successful schools and other city services. “This is a civil rights issue,” he said, noting that beyond referring to shelters’ location, fair share means communities should receive benefits for taking on the responsibility of hosting a shelter. Therefore, he said the city should offer more pre-K or after-school slots when they open shelters and give local nonprofits, restaurants, laundromats and other organizations priority when signing contracts related to the shelter. “If you want to actually go into this dysfunctional marriage that you’ve forced on our folks for so many years, then the community should benefit in some type of way. And we haven’t.”

But curbing the city’s ability to open shelters where many already exist could cut into the government’s ability to aid the homeless, according to Giselle Routhier, policy director at the Coalition for the Homeless. Indeed, she said Lander’s legislation may prevent the city from meeting its legal mandate to house all who need shelter and may run afoul of federal antidiscrimination law by fencing off facilities for the disabled in certain areas. Lander said he was “highly confident” the legislation would withstand legal challenges.

“They define concentration as in relation to the population, not in relation to the need of homeless people,” Routhier said. “We think it’s, on its face, problematic for the needs of families, but also potentially illegal.”

NEXT STORY: Bochinche & Buzz: Barron vs. Bill?