Eric Adams

Eric Adams’ visibility may not mean greater transparency

New York City government has in fact gone backward in several areas, including with law enforcement.

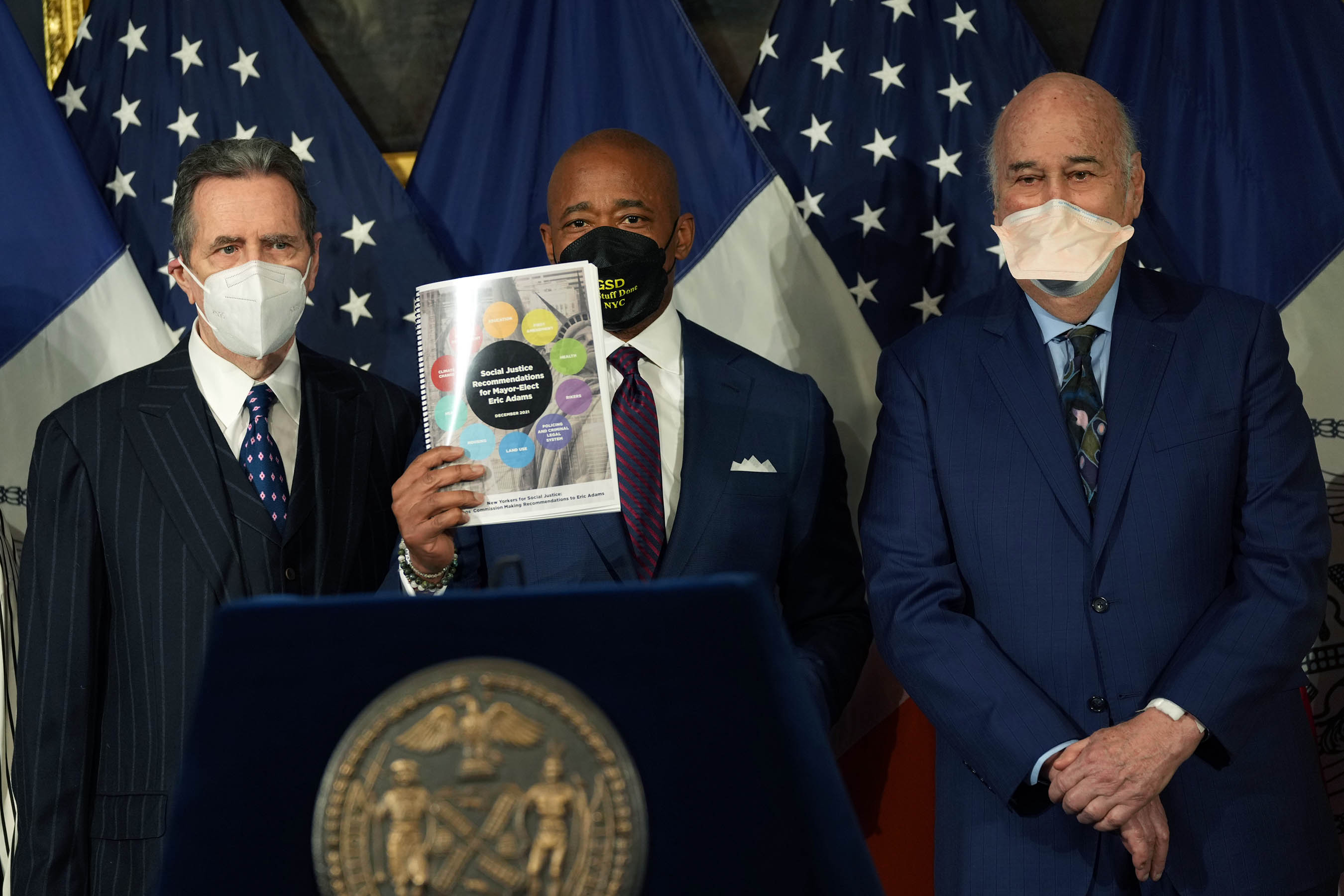

New York City Mayor Eric Adams maintains a busy schedule, but much remains unknown about where he goes and who he meets. Benny Polatseck/Mayoral Photography Office

In February 2022, shortly before New York City Mayor Eric Adams signed an executive order designed to promote transparency at city agencies, one of the people who wrote the first draft received an edit.

Civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, a longtime friend of Adams, led a commission to help the new mayor integrate social justice policies into his agenda. As part of their work, they drafted what would become Executive Order 6. The first version stated that each city agency shall have an “affirmative obligation” to regularly provide information about their work and policies, without the public having to seek that information through Freedom of Information Law requests. The draft also required agency heads to appoint a manager to carry out that work, and review other practices related to freedoms of speech and protest.

But Siegel said shortly before the Feb. 7, 2022, signing, he received the message that City Hall wanted to remove all references to New York’s Freedom of Information Law, including the “affirmative obligation” to provide information “without the public having to initiate FOIL requests.”

The final version that Adams signed required agencies to regularly review policies and practices related to sharing information and other First Amendment rights, and to alter those if they could be improved upon but only “if feasible” – language that Siegel worried would become a loophole that the city could “drive a truck through.”

Siegel said he and the commission wrestled with the changes, but they ultimately accepted them because they saw the order as an historic commitment. “To some extent, they watered it down. But we accepted it, and agreed,” Siegel said of the changes. “And then we had the press conference. He signed it. And we left euphoric,” he added with a dry laugh, “thinking we accomplished some major thing.”

Two years later, Siegel is not sure whether or how the order is being implemented. When City & State asked two dozen city agencies what they’ve done and who is in charge of carrying out Executive Order 6, all but the Department for the Aging either didn’t respond or referred the questions to the mayor’s office.

City Hall press secretary Liz Garcia pointed to examples of public information programs and press availability at seven city agencies – a sampling of how the city has become more transparent. Among other actions, she cited the Department of Buildings publishing new data maps and records, and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development revamping a portal where New Yorkers can learn about violations and lawsuits associated with their residential buildings.

“For two years, the Adams administration has made government more accessible and more effective for New Yorkers,” Garcia said in an emailed statement.

But when asked specifically about the executive order, the mayor’s office declined to provide clear information about how the order is being carried out at city agencies or by whom, or comment on the findings of any reviews agencies have done regarding First Amendment-related practices and policies.

The opacity of the city’s communications about an executive order designed to promote transparency is representative of the way Adams’ promises about government openness and accountability – and similar promises made by mayors before him – have fallen short. Before taking office, Adams told reporters, “I think the press is going to be very proud of the level of transparency I’m going to show.”

Adams is a highly visible mayor, but his overtures about a commitment to transparency have been contrasted with actions that limit access to information available under the previous administration. Those include moves like encrypting NYPD radios and trying to limit a watchdog’s access to video inside city jails that Siegel called “antithetical” to Executive Order 6. These actions over the past two years – several of them concentrated in law enforcement agencies – have left some observers worried about a longer-term chipping away at transparency.

Walls up

Information about the operations of law enforcement agencies is routinely held by the city with clenched fists, and that’s nothing new in the Adams administration. But a series of actions by his administration has continued that tradition, and in several instances blunted tools and discontinued practices that previously allowed the public, press and watchdogs to access information about the NYPD and the Department of Correction.

Police radio channels have been accessible to the public for nearly a century, allowing the press to cover breaking news. But at the end of this year, the NYPD is scheduled to complete a transition to a new system that will encrypt radio communications – a move Adams and the department have said was taken to preempt bad actors, but press, advocates and some lawmakers have decried as a blow to transparency.

The press corps’ physical access to NYPD officials has also changed. At the end of last year, the city moved beat reporters from an office inside 1 Police Plaza in lower Manhattan to a trailer outside police headquarters. Reporters must now agree to be escorted when going through most parts of the building. Described by the administration as a move to increase transparency and allow more outlets to cover the department, the action took reporters by surprise. New York Press Club President Debra Toppeta called it “antithetical to the First Amendment rights of journalists in New York City and everywhere.”

As Rikers Island has continued to prove a dangerous environment for detainees and correction officers, the city has taken steps that limit the flow of information to the press and oversight authorities. Just weeks after witnessing the deadliest year on Rikers Island in years – 19 people in city custody died in 2022 – the oversight board monitoring city jails announced that the Department of Correction had revoked its ability to independently and remotely access video footage from inside jails. It was only after the Board of Correction sued that full access to that footage was restored last fall. The department maintained that they were still able to facilitate any requests for video from the board. But the move cut off the independent access to video that board members said had been a crucial oversight tool for months. “Based on our video access, we know that the department’s internal record keeping is not a reliable source of information,” Board of Correction Member Robert L. Cohen told City & State in an emailed statement recently. “New York City’s jails prefer to work in the darkness. Video access shines a protective light on these violent institutions.”

Last spring, the Department of Correction failed to notify the press of the deaths of two people in city custody, saying that doing so was not required and was merely a practice of the prior administration. “The commissioner wants to respect those who have transitioned while also continuing to be as transparent as possible,” department spokesperson Frank Dwyer said at the time. The department only provided a workaround when pressed on why they weren’t automatically notifying the press of deaths in custody, telling reporters who inquired that they could still be notified, but they had to opt in to those notifications. Asked recently, a City Hall spokesperson said that that policy has ended under Commissioner Lynelle Maginley-Liddie, who took over for former Commissioner Louis Molina late last year, and that the department now sends out press releases about deaths in custody to its media list.

Since Adams is a former cop, some haven’t found the concentration of transparency rollbacks in the realm of law enforcement very surprising. “As someone who wants to be a friend and portrays themselves to be a friend of law enforcement, he’s going to be sensitive to anyone looking over his shoulder, to anyone trying to gain more access to information that would disrupt his sort of narrative and what he believes are the ways in which these agencies should carry out their roles,” said Basil Smikle, former executive director of the state Democratic Party and adviser to then-Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s campaign. But as Adams has revived a controversial policing unit, Smikle said that a brighter light needs to be shone on the department. “How do you bring these things back and then run a police department and be less transparent, not more transparent?”

Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said her organization has had to sue the NYPD under Adams multiple times for the release of detailed data about traffic stops, despite a 2021 law requiring those disclosures. “The contempt for things he claimed were his values back in the day is evident in far too many of the policies and practices of Eric Adams as mayor,” Lieberman said.

“The most visible mayor”

To the extent that transparency is about literally seeing a person, the Adams administration has given itself top marks. “Mayor Adams may be the most visible mayor New York City has ever had – and any reporter wondering what the mayor is up to can attend one of our many public events and ask,” Deputy Mayor for Communications Fabien Levy told Politico New York in December. (Levy did not respond to requests for an interview for this story.)

Proof of Adams’ visibility is in his public schedules, which record his town halls across the five boroughs and his several dozen appearances at flag raising ceremonies honoring diverse communities.

But transparency of the city’s executive and its agencies is not just about where the mayor shows up. “He views transparency as his presence, which then creates a problem because anything else is not transparent, anything else does not matter,” said Democratic consultant Hank Sheinkopf, another former Bloomberg adviser.

Adams’ daily public schedules often reveal an unflagging criss-crossing of the city. But there’s still a good deal unknown about how, and with whom, the mayor spends his time.

Early in 2022, the Adams administration ended an informal – and inconsistent – practice under the de Blasio administration of voluntarily disclosing meetings between lobbyists and top City Hall officials, including the mayor.

Freedom of Information Law requests over the past two years have turned up more detailed daily calendar entries for the mayor compared to what he sends in daily emailed schedules, including more disclosures of internal administration meetings and calls with business leaders. But even those more detailed calendars provide an incomplete picture by often not noting other attendees. Also left out of Adams’ calendars are details about his prolific late-night outings to favorite haunts like Zero Bond and Osteria La Baia.

While de Blasio’s calendars often only made note of a “call” or “meeting,” providing little other detail about what was being discussed, they did provide a fuller picture of whom the former mayor was meeting.

On guard

The most powerful office in New York City invites a much higher level of press scrutiny than that of Brooklyn borough president or state senator, or even a police captain fighting for reform in the department. “You’d have to pull him away from the press conference, as he interacted with the press,” Siegel recalled of press conferences he attended with Adams when he served in those other roles. “He loved it.”

Even some critics agreed that Adams does well in his effort to increase engagement with smaller community and ethnic media outlets across the city. City Hall spokesperson Liz Garcia cited that work when asked about how the administration has improved transparency, saying they’ve been committed to “ensuring that community and ethnic media outlets have a seat at the table.” The Department of Transportation commissioner, for example, has held weekly one-on-one interviews with community and ethnic media outlets.

The move of police reporters to a trailer outside police headquarters was done to make more room for community and ethnic media outlets, Adams has said. He has also said his office would analyze whether outlets in City Hall’s press room need to give up some of their chairs to make room for community and ethnic media outlets.

Ben Max, the former executive editor of Gotham Gazette, and now the executive editor at The Center for New York City Law at New York Law School, said that while he’s seen some “significant steps backward” in transparency since de Blasio, he also gives the mayor credit. “He’s got some issues around sort of press access and control that cut against some of the ways that he’s more accessible, but he really does do a lot of media,” Max said.

But, Adams’ relationship with the press has grown more guarded. City Hall has attempted to limit when reporters can ask questions of the mayor that are deemed “off-topic.”

In place of more open press conferences, reporters are instructed to ask “off-topic” questions of the mayor and other top administration officials at a weekly hourlong press conference at City Hall. Levy has described those weekly briefings as something that will “break down silos and deliver vital information to New Yorkers in a clear, reliable and accessible way.” But the administration has never addressed why those briefings must come at the expense of opportunities to ask “off-topic” questions.

Like mayors before him, Adams believes that he is unfairly scrutinized by the press. As the second Black mayor in the city’s history, Adams has said he’s been misrepresented by newsrooms that lack racial diversity. That criticism can be a valid one, said Christina Greer, a political science professor at Fordham University and a host of the podcast “FAQ NYC.” But it shouldn’t be used as evasion, she said. “You can’t hide behind a valid critique and call people young and inexperienced when you just don’t want to answer the question.”

Picking up the baton

Bill de Blasio tried to control questions from reporters too, and often took on a prickly demeanor with the media.

Bloomberg secretly jetted off to Bermuda on weekends, and may as well have etched “none of your business” in skywriting on his way out. “Withholding information while preaching transparency is a Bloomberg trademark,” journalist Harry Siegel wrote in 2011.

Rudy Giuliani ran a “closed government,” according to advocates. His administration was accused in more than two dozen lawsuits of blocking access to public records, NBC News reported in 2007.

“This particular administration seems to not lean into transparency,” Greer said of Adams. “But I don’t think it’s something new or spectacular that we’ve never seen before.”

Sheinkopf observed that Adams’ approach with the press shared characteristics with multiple mayors, including Ed Koch and Bill de Blasio. “He’s more like Koch in a public way. He’s much more effervescent and more talkative,” he said. “And (with) de Blasio – the attempt to shut down any inquiry into his government whatsoever. What Adams is doing is saying, ‘I’m not shutting you out, I’m telling you what’s going on. And you’re going to have to accept what I say whether you like it or not.’”

Not unlike de Blasio at the beginning of his first term, scrutiny from law enforcement has cast a shadow over Adams and those in his orbit lately. An ongoing federal investigation into Adams’ 2021 campaign is looking into whether his campaign conspired with members of the Turkish government to accept illegal donations. Adams has not been publicly accused of wrongdoing, but his electronic devices were seized in the probe. Other ethical issues have floated around those in Adams’ orbit since the beginning of his term – from the appointment of former NYPD chief Phil Banks, named as an unindicted co-conspirator in a corruption investigation, to the actual indictment of ex-Department of Buildings Commissioner Eric Ulrich and the straw donor scheme organized by former NYPD Inspector Dwayne Montgomery.

“These efforts to tighten control of information are done out of this real focus on sort of public relations and political standing and image, but actually go against what even Adams himself has acknowledged is the best and right way to do things,” Max said.

Chipping away

There’s always reason to doubt a political candidate who makes bold promises about leading a more transparent administration.

“Maybe campaign No. 1 that I covered many years ago, I’d believe them,” one former reporter said. “But no. The minute they get into office they feel, to a certain extent, under siege.”

Others maintain some optimism about becoming more transparent. New laws requiring the disclosure of information, when enforced, can do that. And new administrations have the potential to start from scratch, or even build on existing good practices. “After this administration, you would hope that the next administration would not want to keep some of those kinds of rules,” said Democratic consultant Lupe Todd-Medina. “One can only hope.”

But some observers expressed concerns that actions Adams has taken will contribute to a gradual chipping away at transparency and accountability that the next administration won’t necessarily be motivated to correct. “If we are starting to see more and more negative interactions between police and community, I think the next administration will be confronted with a lot of pressure to rollback these anti-transparency or anti-accountability measures,” Smikle said. “But if that doesn’t happen, I think it’ll largely go unnoticed by most voters.”

“I think it does have a cumulative effect,” Greer said. “Each administration sort of limits their relationship with the press a little bit more, and sort of says, ‘You all are out to get me,’ and it’s a witch hunt conversation. De Blasio loved that conversation. ‘It’s a witch hunt.’” And it’s not limited to City Hall. “(Andrew) Cuomo is the same way. Donald Trump is the same way,” she added, joking that something must be in the water in Queens.

Norman Siegel, for his part, is optimistic about even this administration becoming more transparent. “You’re talking to Mr. Pollyanna here,” Siegel said, noting that relentless optimism is the only option in his line of work.

In 2022, Siegel said he would sue if he found that the requirements of Executive Order 6 weren’t being fulfilled. Today, he’s not sure whether they are. “If it’s not being done, then I’ve got to figure out what I can do, either privately or publicly, to make it be implemented,” he said. “Because I don’t want it just to be a bunch of words on a piece of paper.”

NEXT STORY: NYC Department of Education backs changes to state law to allow fully-remote meetings