This story was developed in partnership with the New York City Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment.

As a breeding ground for artistic creation, New York City in the 20th century had few, if any, peers. What other city could claim New York’s endless diversity of ethnic and creative communities?

Music is part of the city’s mystique. The American songbook, to a large extent, was born in Tin Pan Alley. Jazz fueled the Harlem Renaissance before popular rock ’n’ roll rose out of the Brill Building. From doo-wop in Harlem to hip-hop in the Bronx, whether it's punk in the Bowery or folk revival in Greenwich Village, New York contributed its share – and then some – to the soundtrack of the 20th century.

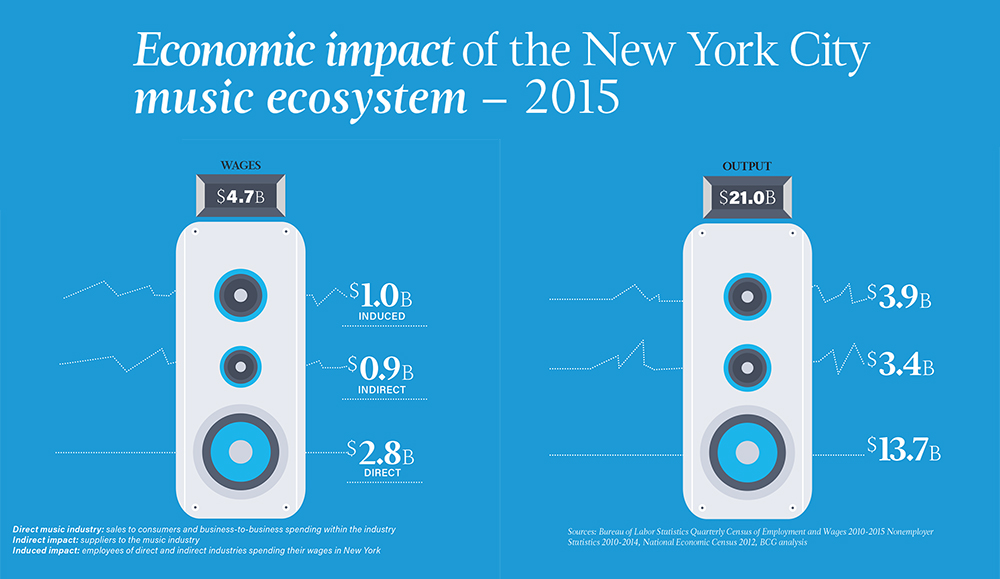

There is no way to measure music’s full value to the city, but a March study conducted by the Boston Consulting Group examined, among other things, the importance of music to the local economy. The report, which was commissioned by the New York City Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, concluded: “New York City is home to one of the world’s largest – if not the largest – and most influential music ecosystems, supporting nearly 60,000 jobs, accounting for roughly $5 billion in wages and generating a total economic output of $21 billion.”

That is not to say there are no weak points or warning signs. There are – which should come as no surprise to anyone who witnessed the transformation of the city over the past quarter century. New York City, in some ways, has become less hospitable to the sort of creators who made it a mecca for the arts. While chasing creative dreams has always required sacrifice, such as the deferral of creature comforts, there is a material difference between fruitful struggle and unrelenting hardship, between obstacles that challenge and those that overwhelm. At the turn of the century, a convergence of forces, each larger than any given industry, shook up the city’s music sector. The real estate market began to soar as digital technology upended 20th century modes of music production and distribution.

The advent of digital technology was a revolution in that it gave as well as took. Album sales plummeted; the global music industry contracted. There was, however, a flipside: new technologies leveled the playing field, empowered the artist and democratized the industry. Some bands found success utilizing less expensive, more accessible recording technologies while digital platforms, such as Bandcamp, allowed independent artists to launch careers without having to rely upon middlemen or corporate backing.

“I worked at labels all through the ’90s, and for so many bands it was like six weeks and out,” recalled Ken Weinstein, a co-founder of the PR firm Big Hassle Media. “You work hard, you produce this record, you put it out and if it doesn't get traction in six weeks – with radio, press or whatever – the label is on to the next thing. Now a band can take matters into their own hands, and label be damned.”

The band Waxahatchee performs at Glasslands in Brooklyn in 2013. (Dylan Johnson)

A CHANGING LANDSCAPE

Due to the growth in digital streaming, global music revenues have recently ticked up, but even chart-topping albums don’t sell like they used to, and recording music is no longer a viable source of income for the majority of artists.

“The price of downloads is a fraction of what they’re actually worth, and there are so many ways to get content for free,” said Tino Gagliardi, president of Local 802 American Federation of Musicians. “Copyright protections are not adequate for today’s digital world or practice. Everyone walks around with a cellphone in their pocket that can stream music, but copyright law was written before YouTube and other digital platforms. The fact of the matter is that access is great, and musicians want more people to hear their music. Technology has helped facilitate that, but more access must also align with fair access to content.”

Median wages for New York musicians may be around $30,000 a year, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data. The wage floor, however, is considerably lower. Making a living as a musician requires more versatility and flexibility than in past eras, such as the ability to perform at theaters, bars or venues for several different employers in a given week or be able to work on a jingle, album or film score.

Even popular artists will release music for free and focus more on apparel and merchandise sales, as well as other media ventures. “The music is just an advertisement for yourself. You need to develop your brand and your image as much as your craft,” said Alex Damashek, the executive director of Move Forward Music, a marketing and event production company. “That’s what you’re going to sell – a lifestyle.”

When album sales began to drop in the late-1990s, bands had to compensate for the lost income by spending more time on tour.

Popgun Presents was born a decade later in the New York University dorms, at a time when more live music was being performed than ever before. Promoters were utilizing new social media tools to reach more consumers who, through digital platforms, were being exposed to a wider variety of music than ever before. A couple subway stops from the university, Brooklyn’s indie scene was popping. That’s where Jake Rosenthal and Rami Haykal, Popgun’s founders, made their move.

For a while, the duo bounced between venues before eventually settling in Glasslands Gallery, which had been primarily a visual art space. By 2011, Glasslands was offering nine shows a week at the Williamsburg venue. Popgun booked artists like Wiz Khalifa and Lana del Rey before they became famous. Rosenthal and Haykal eventually bought and renovated the venue, but in 2014 they were forced to close down.

“It became impossible to coexist with neighbors over there,” said Dhruv Chopra, a childhood friend of Rosenthal’s who eventually joined the team. “Williamsburg’s story had played out.”

RELATED: 25 Brooklyn influencers you need to know

By 2014, the music scene had slid from Williamsburg over to Bushwick, just as it had migrated across the river from downtown Manhattan a few years before. Music scenes have a way of becoming victims of their own success. It’s a familiar story: artists in search of creative space and affordable living gravitate to a previously under-the-radar neighborhood. Bars and venues follow. Before long, young professionals – and commercial establishments catering to their budgets – move in. The process is by no means unique to New York, but in New York the cycle can be hyperaccelerated. In the end, the same market forces that displace working-class families force artists out as well.

Since the turn of the century, many iconic music clubs, such as CBGB – which helped launch the careers of artists like Blondie and the Ramones – have closed. In a 2015 report, the Center for an Urban Future identified 24 music venues (including seven in Williamsburg) that had shut down over the previous four years. These closures often result from some combination of rising real estate prices, zoning pressures, increasing operating costs, noise complaints and licensing problems.

One Williamsburg venue, Galapagos Art Space, announced in 2014 that it would leave New York City after nearly 20 years. A message on its website explained that the city had “become too expensive to continue incubating young artists.”

“If the core competitiveness of the Big Apple is culture, but actually being an artist in New York City costs you a full-time career in another industry, then the best and brightest – the ones our meritocracy would obviously miss the most – won’t allow their work to suffer just to be among our tall buildings,” the message read.

Galapagos is opening a new venue in Detroit.

New York City’s music clubs have played a central role in launching artistic careers as well as new styles of music, whether it was Studio 54, Max’s Kansas City or the Blue Note Jazz Club. Newly minted Nobel laureate Bob Dylan became famous performing in cafes like The Gaslight Cafe.

“You’ve got a city that can sustain a nearly limitless number of accomplished, acclaimed, famous artists, but we’re losing the ability to continue to generate new talent from the root.” – Eli Dvorkin, managing editor of Center for an Urban Future

When Jim Katocin, City & State’s vice president of advertising, worked as a bartender and doorman at The Bitter End in the late 1980s, Bleecker and MacDougal streets formed a buzzing corridor of music. “There were a lot of different bands playing at The Bitter End – literally, four or five a night, all styles of music,” he said. “And those blocks were crowded with venues. Now I think there are only one or two music clubs left on Bleecker.”

Tending bar and working the door, Katocin recalled having conversations with record label people who were always on the lookout for talent. “It was smart on their part because they knew I was there all the time,” Katocin said. “I believe I may have helped a few bands get noticed.”

Though the disappearance of beloved venues affects all music fans, closures hit artists particularly hard. Fewer venues means fewer opportunities to hone and showcase their skills, not to mention earn a few extra dollars.

“I take a lot of pride working with artists when they’re new, putting on the right show for them in New York,” Damashek said.

The spate of closures, however, has limited his options.

“There needs to be those small venues for these kids to go in and fail and try new things,” he said.

The problem is not only the slew of music clubs closing down. It’s that replacing them has become harder and harder. Many of the venues now shuttering date back to the 1970s and ’80s, a more freewheeling era when rules were lax and cheap space abundant, when it was possible to throw a loft party without worrying about the cost, the cops or permits.

“All you needed was a will, a community and a way,” Chopra said.

In contrast, opening a venue today requires investors, architects, designers, engineers – an almost insurmountable barrier if you are only interested in the creative side. “You have to bring in someone with financial acumen,” said Chopra, who studied economics at Yale University.

With Williamsburg in its taillights, Popgun is in the final stages of opening a new venue in Bushwick.

“I think some things are legitimately difficult and some things are unnecessarily difficult,” Chopra said. “Some of it is good and some of it leaves us very exposed.”

Emblematic of the maddeningly complex and, at times, logic-defying bureaucratic terrain entrepreneurs must navigate is the infamous cabaret license that clubs must apply for in order to have dancing on the premise. Entrepreneurs claim that the Prohibition-era law is arbitrarily or selectively enforced – and nearly impossible to obtain. Critics are quick to point out that one of the principal motives behind its promulgation was cracking down on interracial coupling in Harlem’s jazz clubs.

“It became a tool authorities could use to muscle, contain and harass,” said John Gennari, a cultural historian at the University of Vermont.

As property values in a neighborhood go up, so do the noise complaints. Communities turn against nightlife and obtaining liquor and cabaret licenses becomes harder for venues. It has become such an issue in New York that some in the business now believe the creation of music friendly zones may be the only way to sustain a vibrant scene.

“I would like to see part of Bushwick designated a music zone, so it’s a protected thing,” Damashek said.

BIG AND SMALL

When he came onto the music scene, Ric Leichtung was just another amped-up 18-year-old looking for any venue that would let him put on a show. None would. He wound up writing for Pitchfork’s experimental music blog and, when that gig ended, started his own blog and magazine: AdHoc. To raise funds for the publication, Leichtung started organizing music shows at a do it yourself spot: 285 Kent. The venue took off, as did the real estate market, shortly thereafter.

Leichtung later got a day job booking shows at Webster Hall, which he left around the time that AEG Presents, in partnership with the owners of the Barclays Center, bought the venue, which had been family run for 27 years. Opportunities are sparse, according to Leichtung, for an independent promoter to work with established venues, most of which are now controlled by a small number of companies. Since it takes a couple million dollars, along with years of bureaucratic finagling, to open a completely aboveboard venue, Leichtung said people have no choice but to do things in a “quasi-legal fashion.”

“Venues that are legal have a lot of investment and money tied into them, which means they are essentially art institutions that are not in a position to prioritize the art that is happening, and the music that is happening,” Leichtung said. “They are forced to prioritize financial gain, and I think on the whole a lot of the most interesting, engaging and forward-thinking things are not the things that pay the bills, ultimately.”

Leichtung, who recently organized a pop-up performance in a Tribeca boxing ring, believes that legal venues can no longer nurture the kind of culture and artists that will keep New York a “relevant” city. “We don’t do (DIY) because we like it; we do it because we have to. Nobody wants to get tickets or unexpectedly go to jail for a night,” he said.

With growth in the live music sector, and the myriad barriers to entry, large companies have expanded their market share in recent years.

“Live Nation is the largest live entertainment company in the world,” said Jason Stone, a vice president at the company, which has been rapidly growing in the New York market. “We are very diverse and have a variety of experts on staff that deal in the municipal sectors as well as in the private business sectors and can navigate their way effectively through any type of licensing and zoning restrictions.”

And while large companies undoubtedly bring legitimacy to the sector, their critics question the amount of attention they pay to small venues and the nurturing of new artists – a concern that Stone dismissed as baseless.

“We nurture at the smaller level of emerging artists on a regular basis with 300 events at the Gramercy Theatre, with another maybe 250 events at Irving Plaza. These are buildings in the New York marketplace that are 500, 600, 700 seats – up to 1100 seats – so these are places that we are always nurturing up-and-coming artists.”

In addition, Stone said, emerging artists open for the top talent in Live Nation’s larger concert facilities and comprise a large portion of the acts at music festivals run by the company.

“We are very involved in emerging talent and building artists from the first step all the way up to stadiums,” he said.

With the big players in the market, live music is booming. According to BCG, New York is the global leader with upward of five million tickets sold to marquee events every year. That is 30 percent more than the next highest city, London. “In New York City it is essentially standard operating procedure for major shows to sell out in minutes,” the report stated. “This high demand for live performances suggests that the concert and festival market has not hit its saturation point.” BCG also reported that between $400 million and $500 million in tourism spending can be attributed to music-related events, and that the music festival sector also has potential for additional growth.

Aided by the proliferation of social media, music festivals around the country have exploded in popularity in recent years. Since it was founded in 2011, the Governors Ball Music Festival, an event held annually on Randall’s Island with four stages and many different music genres, has made an effort to showcase the visual art, music and food of the city as well as local communities.

“From the very start of our business, we wanted to have as much New York City flavor as possible,” said Tom Russell, a partner at Founders Entertainment, the company that launched the festival. “That includes on our staff. That includes in our programming, the musicians that we book, the artists that are doing murals on site, the food vendors that are selling food. We want it to scream New York City in every way possible.”

Acts you see busking in the Union Square subway station may later turn up on the grounds of a local music festival. “You’ll see pop-up performances around site from dance troupes that are based in Queens or the Bronx,” Russell said. “You’ll see mariachi groups (from Washington Square Park) surprising people as they’re waiting for a band.”

According to an economic impact analysis of the Governors Ball Music Festival commissioned by Founders, each event generates $50 million in economic impact. And while the festival may only come once a year, it provides local artists and eateries with opportunities to grow their fan base and customer base.

“Venues that are legal have a lot of investment and money tied into them, which means they are not in a position to prioritize the music that is happening. They are forced to prioritize financial gain.” – Ric Leichtung, events director, AdHoc Presents

“It’s truly amazing how many local New York City folks come to all three days of our event and spend money and learn about local food vendors, and learn about local artists, and then go to those restaurants throughout the year and seek out those artists throughout the year,” Russell said.

While the economic and cultural benefits of a vibrant live music scene are clear, for some people the overarching question still remains: Is it possible for the ecosystem as a whole to flourish in the long term if the grass-roots artist community, which accounts for a fifth of its total jobs, flounders?

“New York City is becoming so expensive that artists and musicians find it hard to establish careers here, clubs struggle to survive, rehearsal space is scarce and expensive, and the audiences that support both cannot afford to live in the city,” said Richard James Burgess, CEO of the American Association of Independent Music, an organization representing independent record labels. “None of this adds up to optimistic projections for a vibrant New York music scene the like of which spawned hip-hop, disco, the folk revival, doo-wop, bebop, and the many other forms of music that might not exist if it were not for New York’s innate support of new forms of artistic culture.”

For Eli Dvorkin, the managing editor of the Center for an Urban Future, the big question is whether New York will continue to produce the Madison Square Garden headliners of tomorrow, or whether it will just serve as a home for rock stars?

“The risk that we’re running is that New York becomes too top heavy,” Dvorkin said. “You’ve got a city that can sustain a nearly limitless number, it seems, of accomplished, acclaimed, famous artists, but we’re losing the ability to continue to generate new talent from the root. A tree with incredibly heavy branches up top and a weak infrastructure at the roots is eventually going to topple.”

Since 2000, rents have tripled in neighborhoods with the highest concentration of artists, according to Dvorkin, and New York is running the risk of losing grass-roots music communities to cities with substantially lower costs of living. “The music scene in Nashville has quadrupled; in Portland it’s tripled,” he said. “So even as we continue to grow a little bit in New York, there are other cities that are vastly more affordable and doing a pretty good job of saying to artists and musicians: ‘Why struggle so hard in New York? Come here, we have resources for you. You can afford to be artists here.’”

Dvorkin believes the city should create more permanent affordable spaces for artists to serve as cultural anchors in neighborhoods and allow arts production to happen without the attendant five- or 10-year cycles of rent increases and displacement.

The artist community itself, of course, is an anchor for the rest of the music ecosystem, including publishers, record labels, recording studios, digital service providers and music schools. And music is one of many creative sectors that has made New York City a magnet for top talent as well as tourist dollars.

“As much as banking is important to the city, think of what actually draws you to the city,” said Daniel Glass, the president of Glassnote Records. “Music. Broadway shows. Art. Museums. Liberation. You don’t come because Citibank is here. You come because you want to see fashion, art, ‘Hamilton’!”

Just as proximity to its music sector lures companies from other industries to New York, music companies likewise benefit from their proximity to other hubs, such as advertising, media and finance.

Marcie Allen started MAC Presents, a sponsorship and partnership agency, in her Nashville dining room. In order to take her business to the next level, however, she had to get closer to the brands and their Madison Avenue agencies. “I’m located in the Flatiron (District) and just within a 10-block radius you’ve got everything from Samsung’s new headquarters to Live Nation’s headquarters to Google to Spotify to Sony Music to Anheuser-Busch,” she said.

For Nicole Stillings, aka DJ Rosé, playing music started out as a hobby, a way she managed stress from her marketing job managing digital campaigns for corporate clients. After a while, she realized it was her true calling. Stillings quit her job and started spinning at nightclubs around the city. She worked late hours and the money wasn’t great. What’s more, the clubs that contracted her were facing the same cost pressures as live music venues – providing their bottle service clientele with a steady stream of Top 40 hits, not the ideal creative outlet. She eventually pivoted back to the corporate world, taking on several brands as clients, including Samsung, W Hotels & Resorts and Saks Fifth Avenue. While Stillings will still spin a set or create a playlist for a big event, she has a grander vision for her work, ultimately, as more of a musical director.

“I am trying to teach my partners that they need a one-stop shop to handle all of their music needs, Stillings said. “Brands and companies are starting to understand how much music is a very large part of marketing,” she said.

Stillings wants to help brands “take back control of their message through music,” which she sees as a relatively inexpensive way to cut through advertising noise that bombards consumers. “Music is an emotional connection with your customer and the brand is really doing itself a disservice by not purveying their marketing message through music,” she said.

Frank Sinatra signs his induction papers in 1943. (Fred Palumbo/Public Domain)

THE LEFT COAST LURE

The pop music world began shifting to Los Angeles after World War II. As the home of the radio broadcast industry, New York City had been the epicenter of the jazz and popular music world, but when TV started replacing the radio in the American living room, some of the industry's brightest stars, like Frank Sinatra, decamped for the West Coast to pursue crossover careers in Hollywood. Jazz musicians soon realized they could make a better living playing pop or rock, working in film and television.

“What made it synergistic in the case of LA is that the studios took music really seriously and commissioned original music for television series and films and TV shows had live bands,” Gennari said.

New York City came to be known more for its avant-garde scene. Jazz, for instance, moved down to the Greenwich Village from Midtown and became more associated with literature and the visual arts. Other musical genres that emerged, such as punk, were connected to the alternative art scene. “This is very important to history of the music, but it’s not where the money is,” Gennari said.

Until recently, however, the pop music world kept a foot on each coast, and New York City would still produce its share of commercial hits. “Historically, it’s been cyclical,” explained Jeffrey Rabhan, chairman of the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. “New York would be big for 10 years, then LA would be big for 10 years … now artists looking to make records in a studio only have one choice, and that’s to make them in LA.”

It was New York’s skyrocketing real estate market that drove producers to LA, with its relative abundance of land and space. A multiroom facility in California could be had without breaking the bank. “When the producers moved, the artists moved; and when the artists moved, the writers moved and the managers moved,” Rabhan said. “Many of the labels are still headquartered here. They consider New York home. But producers and artists – those numbers have diminished significantly in the last decade.”

According to Ann Mincieli, the owner of Jungle City Studios, the migration to California has “been a growing problem for years, but it’s hit an all-time low and people aren’t coming back anymore. The (production) budgets aren’t as big as they used to be. Not every artist can go back and forth.”

“Think of what actually draws you to the city. You don’t come because Citibank is here. You come because you want to see fashion, art, ‘Hamilton’!” – Daniel Glass, president of Glassnote Records

New York Is Music, a coalition of more than 200 organizations, analyzed data from recording sessions of top-selling albums between 1999 and 2014 and concluded that New York’s share of those projects had declined nearly 50 percent.

In order to stabilize its production infrastructure and reverse the exodus, many in the local industry are now urging New York to follow other states – including California, Georgia, Louisiana, Tennessee and Texas – and offer tax incentives.

Last year, a bill that would have authorized up to $25 million in tax credits for the music industry passed the Assembly and state Senate with broad bipartisan support. The legislation would have created a baseline 25 percent credit on qualified expenditures, with upstate counties eligible for an additional 10 percent, on production-related expenditures such as the salaries of session musicians, as well as programmers, engineers and technicians and studio rental fees.

“This (tax credit) attracts technical-side people who have a really unique set of skills that cross into the digital realm,” said William Harvey, co-founder of New York Is Music. They're not one-dimensional. They're the kind of workers that every city on the planet is trying to attract.”

Gov. Andrew Cuomo wound up vetoing the bill last year and the tax credit did not make it into this year’s budget either.

“Some tax credits don’t see a return on their investment, but the creative arts industry is not like all the others,” said Assemblyman Joseph Lentol, one of the bill’s co-sponsors. “The state has seen a return on the film tax credit and they will surely see a return on the music and video game production tax credit.”

When the city’s production community was larger, it was not uncommon for record labels to redirect artists to New York City, even those based on the West Coast.

Gregg Wattenberg, a songwriter and producer, said, “Record companies just want to send artists to wherever they will get the most songs – and the best songs. So if there are a 100 songwriters in LA, and only 20 in New York, and you have a month to get your songs together, you are going to put them in the city that has the most songwriters.”

But once a critical mass of creative talent begins to flow from one hub for another, it can set off a chain reaction. Young songwriters, after all, need to be in the room with artists – and vice versa. And LA, many fear, is becoming increasingly the default destination for newcomers looking to get ahead in the industry.

“I’m in a business that’s an odds game and I have to play as many chips on the table as possible,” explained Wattenberg, who has produced and co-written No. 1 hits for artists such as Phillip Phillips and Train. “I’ve got to write as many songs, in as many rooms, with as many artists over the course of five years to increase my chances of becoming successful.”

New York's Madison Square Garden, where The Grammys will be returning for the first time in nearly 15 years. (EQRoy/Shutterstock)

THE GRAMMYS

When she joined the New York City Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment last year, Commissioner Julie Menin took on an expanded portfolio – one that included, for the first time, the city’s music industry. In one of her first big moves at the agency, Menin negotiated to bring the Grammys back to New York City after a 15-year hiatus. The awards show is expected to bring $200 million in economic benefits to the city. More important, for some, is the signal it sends about New York’s ambitions as a music capital.

“The 60th anniversary (of the Grammys) in New York would be major,” Mincieli said. “It would be the start of trying to turn the tide.”

According to the BCG report, awards shows “bring together key players in the music business, offering a chance to showcase investment opportunities within the five boroughs and to give a firsthand look at all New York City has to offer.”

Craig Kallman, the chairman and CEO of Atlantic Records, welcomed the attention that the city is now paying to music, given the industry’s well-documented struggles of late. Citing the city’s success in boosting local film and television production, Kallman said, “The momentum that the city has in its focus on the arts and all these critical areas, I think they all absolutely feed off each other, so it's really exciting.”

That New York City emerged from the past two decades as the nation’s largest music cluster is a testament to the overarching strength of its economy. While digital technology wiped out many production jobs, New York City managed to offset some those losses with offshoots of old industries, including distribution jobs added by companies like Spotify and Amazon Music. YouTube, Soundcloud, Sirius Satellite Radio, Pandora and Vevo are among the other 70-odd companies in digital music services that now have major operational hubs in New York.

“The 60th anniversary of the Grammys in New York would be major. It would be the start of trying to turn the tide.” – Ann Mincieli, owner of Jungle City Studios

But why New York – as opposed to Silicon Valley or LA?

Apart from geographic advantages like the time zone and proximity to Washington, D.C., the city can offer a strong talent pool that combines creative and engineering skills. “Many engineers who want to work in the music space are also in bands or want to see music,” said Joe Conyers III, the general manager of Songtrust. “LA’s tech community is also still quite behind San Francisco and New York, especially in terms of ad tech.”

It helps that major tech companies like Google and Facebook have opened up hubs in the city. But New York’s competitive advantage continues to be its status as the country’s largest creative hub, in addition to the opportunities arising out of location-based synergies with other industries.

While Boston may excel in one industry like biotech, “New York is at the intersection of all these other industries,” Dvorkin said. “So where music meets tech, that’s where New York is going to have a competitive advantage. Where finance meets tech, same thing – or fashion, or new media like podcasting.”

In the new digital world, artists are increasingly branding themselves through partnerships with streaming companies, resulting in LA-based artists spending more time in New York. That has resulted, in turn, in more foot traffic directed to local studios.

“We do shoots all the time for YouTube and Pandora and Spotify and Apple,” Mincieli said. “We do some of the shows right from our studio. It’s revenue streams that we might not have had years ago.”

Mincieli admitted, however, that the studios still “need to sort some of this stuff out.”

“It’s the wild, Wild West,” she said. “All new rules are being written.”

Studios, it turns out, are not the only ones still grappling with how to position themselves relative to the companies that have turned their world upside down.

“iHeartRadio, Clear Channel – terrestrial radio’s big players are about to go bankrupt,” said Dennis Lord, an executive vice president at SESAC Holdings, a music rights organization. “The (digital service providers) – Spotify, Amazon, Pandora – that’s the key to our growth.”

“We are relying for growth on the people who brought us down in the first place,” he added.

Correction: Nicole Stillings' name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.

NEXT STORY: Publisher's Section