New York State

The other reason the Dems don’t control New York

Rich Schaffer has made Suffolk County politics in his image, but at what cost?

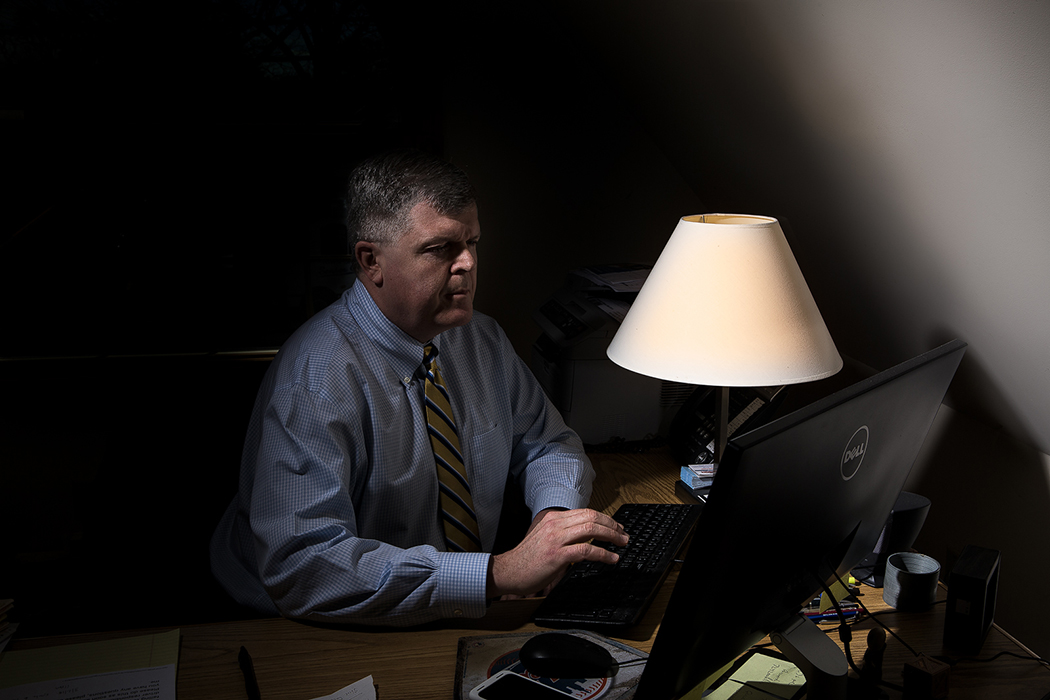

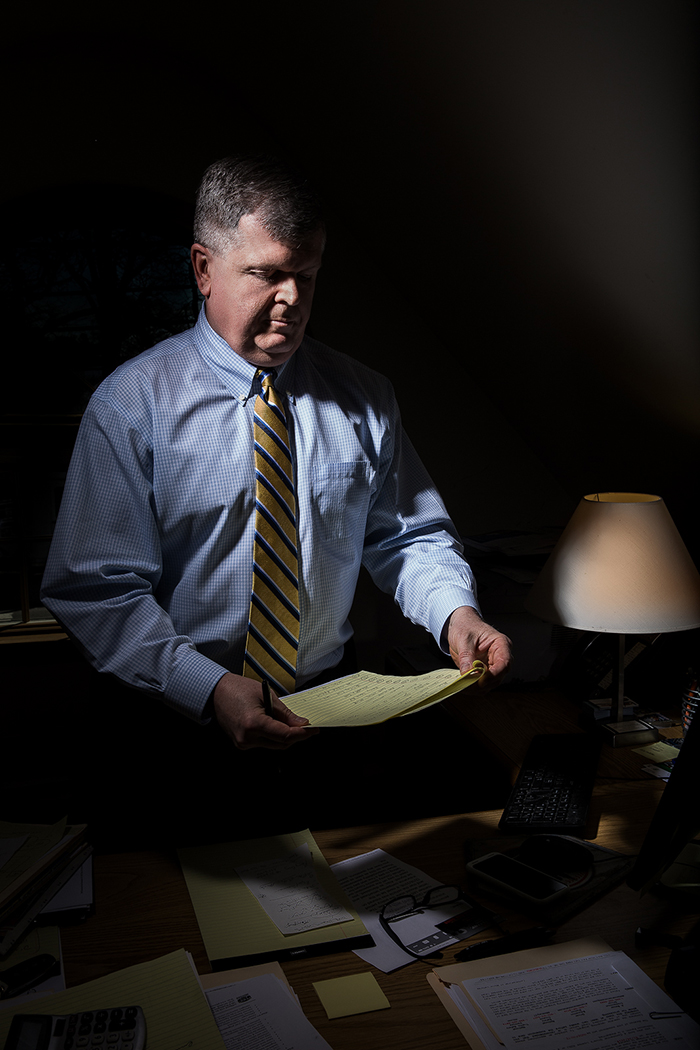

Suffolk County Democratic Committee Chairman and Babylon Supervisor Rich Schaffer. Emily Assiran

For years, Democrats have been on the verge of seizing the state Senate. Sometimes, they’ve been stymied by the Independent Democratic Conference and its power-sharing arrangement with Republicans. Other times, they’ve been blocked by state Sen. Simcha Felder, a Brooklyn Democrat who caucuses with the GOP. Gerrymandered districts have also played a role, including the creation of a 63rd state Senate seat tailor-made for a Republican in the last round of redistricting.

But there’s another culprit that few people consider when pointing fingers over failed attempts to take the Senate – Rich Schaffer, the Suffolk County Democratic Committee chairman and Babylon supervisor.

Critics whisper that Schaffer has allowed Republicans to maintain control of winnable Suffolk County state Senate seats by propping up patsy Democratic candidates to run while negotiating backroom deals across all levels of state and county government.

On Schaffer’s watch, Republican state senators have thrived, most notably state Sen. Phil Boyle and his predecessor, the late state Sen. Owen Johnson. In 2014 and 2016, Boyle faced a Schaffer-endorsed Suffolk County Board of Elections staffer who didn’t raise a cent, and this year Schaffer is backing an unknown political rookie to take on Boyle.

Schaffer has had a startling indifference or even outright opposition toward Democratic candidates, including some who lost, like Boyle’s 2012 rival Ricardo Montano, and some who won, like state Sen. John Brooks and Assemblywoman Christine Pellegrino. He has gained a reputation for negotiating cross-endorsement deals with third parties that ideologically conflict with Democrats, such as the Conservative Party. As if his questionable political deals weren’t enough, he also is cozy with controversial figures like former Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota, who was indicted by federal prosecutors late last year.

“He is the biggest obstacle to a Democratic state Senate on Long Island, and Long Island is the most important part of flipping the Senate,” Bill Lipton, New York state director of the Working Families Party, said about Schaffer.

Schaffer is the Democratic leader in a county that is almost unique in its tradition of split-ticket voting, navigating its more conservative culture alongside a rising wave of progressive activism and shifting demographics. But his transactional brand of politics and dealmaking has angered residents who believe that he has not only presided over a culture of corruption in county politics, but allowed it to flourish for his own benefit.

“I love the politics. I like the government, but I love the politics,” Schaffer told me in an interview. “Everything is politics.”

Schaffer strikes up conversations in the deli every morning between the cashier’s counter and the fridges containing soft drinks. He greets every person who enters by name, a one-man welcoming committee.

“People pull me aside about a constituent thing going on in their neighborhood, or tell me their political views on things,” Schaffer said about the regulars who visit the deli. “It’s a good little gathering spot.”

Most days, Schaffer meets with two young men he is mentoring, Steven and Nick Dellavecchia. Schaffer has known the Dellavecchia brothers since they were kids, as their father has been picking up and dry cleaning Schaffer’s shirts since 1988. Steven, who is 24, is recovering from drug and alcohol abuse. Schaffer talks about him in an avuncular way, proudly noting that he was an honor student before he began using drugs in 11th grade. Steven and Nick both have jobs with the town of Babylon.

In interviews with more than a dozen of Schaffer’s friends and colleagues as well as current and former county officials, a portrait emerged of a politician who thrives on retail politics, and on using his personal relationships to maintain the Democratic majority in the County Legislature.

But some argue – including many who refused to talk to me on the record out of fear of political reprisal – that he is more concerned with maintaining his own power as the kingmaker who decides who will win and lose at every level of county government.

“I love the politics. I like the government, but I love the politics.”

Suffolk County, which comprises the eastern half of Long Island, has a population of 1.5 million, making it larger than 11 states. In 2008 and 2012, the county voted for Barack Obama. In 2016, it backed Donald Trump by a nearly 10-point margin. In Congress, Suffolk County is represented by Republican Reps. Lee Zeldin and Pete King and Democratic Rep. Thomas Suozzi.

The county’s state Senate delegation is largely Republican, headed by Majority Leader John Flanagan. In the 1st and 2nd state Senate districts, Republicans have a voter enrollment advantage over Democrats. However, in the 3rd and 4th districts, registered Democrats outnumber Republicans, providing Democrats with a possible path to victory. Republican state Sen. Tom Croci, in the 3rd District, recently announced his upcoming retirement, leaving a critical seat open. The portions of the 5th and 8th districts that are in Suffolk County have more Democrats than Republicans. But Republicans have held all or most these state Senate seats for years.

Schaffer readily admits that a Democratic-controlled state Senate is not his top priority. In 2009, when Democrats took the state Senate, they passed a payroll tax for downstate counties to help fund the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Schaffer said he had urged a new Democratic state senator in Suffolk County, Brian Foley, not to vote for the legislation, which was deeply unpopular in his district.

In 2010, GOP candidates on Long Island campaigned heavily against the MTA payroll tax, and Republicans reclaimed the state Senate majority. Foley, who voted for the tax, was defeated by Zeldin, who went on to unseat Democratic Rep. Tim Bishop in 2014.

More stinging to Schaffer, however, was how the tax affected the County Legislature. Brian Beedenbender, a Democratic county legislator, lost his seat to a Republican in 2009 after the local GOP campaigned heavily against the MTA tax.

“Until they can prove to us that they’re going to give the suburbs just as equal billing as the city, I’m not going to get out of my way to help,” he said about the state Senate Democrats.

Yet Schaffer’s lack of cooperation with Democrats in the Senate predates the MTA tax, most notably his decadeslong unwillingness to run a significant challenger against Johnson.

In the late 1990s, when Schaffer was supervisor of Babylon for the first time, the town was on the verge of bankruptcy. Schaffer asked Johnson, a West Babylon native, to support a bill allowing the town to borrow funds to close the deficit and continue its operations. Johnson sponsored the bill over the opposition of local Republicans and the state Senate GOP leader. Afterward, the two collaborated on mutual political priorities in Suffolk County, and Schaffer only put up token Democrats to challenge him.

Schaffer told me that near the end of Johnson’s life, a Newsday reporter asked him when his deal with Johnson would end. “I said, two ways: One, when he says it’s over, or when the good Lord takes either me or him from this earth,” he recalled.

His deal with Johnson seems to have extended to his successor, Boyle. In 2012, Montano challenged Johnson. Schaffer offered no support to Montano out of his loyalty to the ailing Republican, who dropped out of the race after Montano filed enough nominating petitions. Montano was defeated by Boyle, who garnered 53 percent of the vote.

Steve Levy, who served as Suffolk County executive from 2003 until 2011, said the Montano race demonstrated Schaffer’s willingness to take out political enemies. “When somebody burned him – like Rick Montano, who was a county legislator – he did everything he could to take him out, and he did,” Levy said. “But he knew beforehand that he would be able to.”

Boyle’s Democratic opponent in 2014 and 2016, John Alberts, provided little competition and raised and spent no money in the 2016 campaign. Boyle defeated him comfortably both times, with more than 60 percent of the vote. This year, Schaffer endorsed Bailey Spahn, a 20-year-old Hofstra University student. Schaffer told me in February that he didn’t think the Democratic Party had much of a chance of taking Boyle’s seat. “I know Boyle well. He does his homework. You’d need to spend over $1 million to defeat Phil Boyle,” he said.

A recent Daily News article suggested that Gov. Andrew Cuomo was reaching out to Democratic state Senate candidates on Long Island because Schaffer could be collaborating with Senate Republicans.

Democrats do control nearly every lever of local politics, Schaffer’s allies are quick to point out. Suffolk County has a Democratic county executive, sheriff, district attorney and legislature.

But critics wonder why a Democratic chairman would choose between prioritizing local or state races.

“Why is it an either-or?” Lipton asked. “In the age of Trump, is he just focused on the County Legislature?”

Schaffer’s intensity, and his reputation for targeting enemies, may have been earned in part because politics is his all-consuming passion. He admits with a laugh that he has “no life.” He is unmarried and spends most of his time tackling town or county issues.

“I’ve dealt with quite a large number of chairs, and you’re not going to find another chair that’s more talented politically than Rich Schaffer in New York state,” said Jay Jacobs, the Nassau County Democratic Committee chairman and former state party leader from 2009 to 2012.

Or as Long Island Association President and CEO Kevin Law, who has been a friend of Schaffer’s since the two worked for former Assemblyman Patrick Halpin in the 1980s, put it: “He lives, eats and breathes politics and government.”

One of Schaffer’s first campaign experiences was in 1974. His friend Jeff’s older brother, Tom Downey, was running for Congress. “The only way we would get to play on the trampoline or go on the tree fort was we had to go with Mr. Downey, Tom and Jeff’s father, load up in the little light blue Volkswagen station wagon and he would take us and just have us deliver flyers up and down streets,” said Schaffer, who was paid in pizza.

Politics provided an escape from his difficult family life. His father left the family when Schaffer was 10, leaving four children with an alcoholic mother who later killed someone in a drunk driving accident. “I was kind of in charge at 10, 11, 12,” Schaffer said. “I grew up pretty quick.”

Schaffer met his mentor, Halpin, and went on to become a county legislator and eventually an assemblyman. They stayed in touch while Schaffer was in college at the University at Albany.

Halpin thinks that Schaffer learned his lesson about the importance of local politics the hard way. He became president of the university’s student body and spearheaded a drive to register student voters. In Halpin’s telling, the students used their political activism to target the Albany Democratic machine, which was one of the strongest in the state.

“Rich starts rallying against the Albany machine on television and in the newspaper, and the next thing you know, the Albany Democrats through their elected officials in the state Legislature – in the Assembly and the Senate – cut the funding for projects at SUNY Albany,” Halpin said, clearly relishing the chance to tell a story he enjoys.

Schaffer called Halpin, who was in the Assembly at the time, to ask him to tell the then-mayor of Albany, Thomas Whalen, that Schaffer had learned his lesson. Halpin told Whalen that Schaffer was a good Democrat who would be graduating at the end of the year, and that he hoped the mayor would continue to support the university.

“The mayor listens politely. And he said, ‘Well, we’re going to let young Richard stew for awhile. But tell him to behave himself,’” Halpin recalled. “So that was Rich learning his lesson about power politics in New York state.”

After he graduated, Schaffer worked in Halpin’s Assembly office and attended Brooklyn Law School at night.

In 1987, Schaffer was elected to the County Legislature, and Halpin was elected county executive. In 1992, Schaffer was elected for the first time to be supervisor in Babylon, presiding over the town board, and became the Suffolk County Democratic Committee chairman in 2000. He was succeeded as supervisor by a protégé, Democrat Steven Bellone, in 2002, then was elected back to the post in 2012. Bellone is now the Suffolk County executive.

I mentioned to Halpin that the man who once fought the Albany Democratic machine is now considered by many to represent the Suffolk Democratic machine.

“Yeah, isn’t that interesting?” Halpin agreed, chuckling. “That’s interesting.”

“I’m going to do everything I have to to get the Democrats elected, and if that means working with a particular party in a particular race, I’m going to do that.”

In 2016, Schaffer declined to endorse John Brooks, the Democrat who was challenging Republican state Sen. Michael Venditto. Schaffer called Venditto “a good Republican” before the election, according to the Daily News. Brooks narrowly defeated Venditto, whose father, then-Oyster Bay Supervisor John Venditto, had been indicted on corruption charges. This year, Schaffer said he is supporting Brooks for re-election.

Schaffer has made a habit of offering half-hearted support to other Democratic state Senate candidates. “You would think a county leader of a particular body would be supportive of all the candidates of that party. He doesn’t work that way,” said a source with knowledge of the situation between Brooks and Schaffer, who requested anonymity to speak candidly.

Several sources said Schaffer had also given insufficient support in 2016 to Jim Gaughran, who ran against Republican state Sen. Carl Marcellino and lost by just over 1,500 votes. Schaffer denied this, noting that he donated $1,000 and loaned $10,000 to Gaughran’s 2016 campaign. Gaughran, who is running against Marcellino again and has been endorsed by the WFP, confirmed that he had Schaffer’s support.

Schaffer also did not support Pellegrino, who won a special election last year for a vacant Assembly seat in a solidly Republican district. The Republican candidate, Tom Gargiulo, was the vice chairman of the Babylon Conservative Party. Schaffer was negotiating behind the scenes to install Gargiulo as tax receiver in Babylon, according to State of Politics, but the position was already filled. Gargiulo then ran for Assembly, claiming to have Schaffer’s support. Meanwhile, Schaffer was reportedly trying to get the Conservative Party to cross-endorse Democratic Suffolk County District Attorney candidate Timothy Sini.

Schaffer and Jacobs, the Nassau County Democratic chairman, had officially chosen another Democrat, Ben Lavender, for the Assembly seat, but Pellegrino was fired up to run. Since Schaffer was unwilling to offer her support, the WFP and New York State United Teachers decided to endorse her, Lipton said. After Jacobs and Bellone got behind Pellegrino, Schaffer put her on the Democratic line. Pellegrino won a surprising 58 percent of the vote.

Schaffer said he was unable to participate in the race because he was a witness in an investigation by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. involving NYSUT’s unsuccessful attempt to earmark $100,000 for a state Senate candidate in 2014.

But Schaffer did not appear to help to Pellegrino last year even after Vance closed his inquiry.

Jacobs said that the Nassau County Democratic Party was able to offer more support to her candidacy because Nassau is more left-leaning. “I was in an entirely different place, and I have a lot more latitude to make the moves that I might prefer to make,” Jacobs said.

When reached for comment, Pellegrino said that her relationship with Schaffer has been positive since her election. “Rich Schaffer and I are working together on a number of initiatives to get new people involved with the Democratic Party in Suffolk County,” Pellegrino said. “He is 100 percent supportive of my re-election campaign.”

The Pellegrino race also highlighted a simmering tension between Schaffer and Bellone, who supported Pellegrino long before Schaffer did. This feud also played out during last year’s county district attorney race, when Sini was considered the candidate favored by Bellone. John Jay LaValle, the Suffolk County Republican Committee chairman, told Newsday at the time that Schaffer thought Sini was “Bellone’s guy.”

“But there was no realistic chance to stop Sini, so he capitulated,” LaValle told Newsday after the Democratic Party endorsed Sini last June. LaValle did not return requests for comment for this story.

Schaffer said he met with Sini in August 2016 and told him that he would support him, but he needed to work behind the scenes first to obtain cross-endorsements from minor parties first.

Even if Schaffer was covertly supportive of Sini throughout his candidacy, the perception was that he was ignoring yet another progressive, WFP-endorsed candidate. Lawrence Levy, executive dean of the National Center for Suburban Studies at Hofstra University, defended Schaffer, saying that he could “hardly fault a political professional” for not actively campaigning for Brooks and Pellegrino, who were seeking solid Republican seats. However, he said that Schaffer could be more open to backing upstart challengers.

“If Schaffer continues to miss potential upset candidates, eventually he will pay a price politically,” Levy said, “because folks will begin to question his judgment, and, as some are doing now, his motives.”

“I guess I’m a homebody.”

In 2006, Cuomo was seeking the Democratic nomination for state attorney general. He reached out to Law, now the Long Island Association president and CEO, who recalled telling the candidate to attend a fundraising dinner held by Schaffer. Schaffer had attended the University at Albany with Cuomo’s sister, Madeline, and volunteered on Mario Cuomo’s 1982 gubernatorial campaign. The younger Cuomo was unable to attend the dinner, but the elder Cuomo made an appearance. At the dinner, Schaffer committed to supporting Andrew Cuomo for attorney general.

“All the folks running for AG were trying to get Richie’s endorsement,” Law said. “That helped propel Andrew to win the AG’s race.”

Once Schaffer made his endorsement, Law said, other county chairs followed suit. Schaffer later became the first county leader to endorse Cuomo for governor in 2010.

Schaffer’s power as a kingmaker, however, can also get him into political trouble. He is famous for making cross-endorsements, negotiating with leaders of other parties, notably the Conservative Party, to get candidates on multiple lines.

“When his line represents approximately 15 percent of the vote and neither major party gets you over 50, the Conservative Party becomes critical. It’s just a matter of numbers,” Schaffer told Newsday in 2016 about former Conservative Party leader Ed Walsh, who was later convicted on federal corruption charges.

Walsh’s attorney, William Wexler, works in the same law office that Schaffer now uses to conduct his political business. Schaffer denies that he has any interaction with the office’s business. Wexler is also a part-time assistant attorney for Babylon and counsel to the town’s Industrial Development Agency. Wexler’s wife has donated extensively to both the Babylon and the Suffolk County Democratic committees.

Many in Suffolk County tout Schaffer’s role in getting Errol Toulon Jr., the first African-American nonjudicial countywide elected official, elected sheriff. But rumors circulated last summer that Schaffer was supporting Boyle for Suffolk County sheriff, even though the state senator had the Republican nomination. In June 2017, the Conservative Party, which had often cross-endorsed Democratic candidates, backed Boyle, a Republican, for sheriff, and Sini, a Democrat, for district attorney. Schaffer then said that he was open to putting Boyle on the Democratic line, angering LaValle, who had recently blocked the county Republican Party from accepting Democratic cross-endorsements in nonjudicial races.

LaValle extracted a written affidavit from Boyle at the Suffolk County Republican convention promising not to run on the Democratic line. LaValle swore he would tear up the nomination of any candidate who refused the pledge. Boyle signed it, and became the Republican nominee.

However, this did not end speculation that Boyle would secure the Democratic line. A petition obtained by City & State from the town of Riverhead Democrats showed Boyle appearing alongside Democratic candidates for district attorney and judge. Schaffer denied having circulated the petition. “We knew nothing about it,” he said.

Shortly before the primary, the Daily News reported that if Boyle won, Schaffer had agreed to let Republican Suffolk County Legislator Tom Cilmi fill the open state Senate seat, and Republican Islip Councilwoman Trish Bergin Weichbrodt would take Cilmi’s place in the County Legislature.

Cilmi told me that he had conversations with people in the state Senate and local Republicans about seeking the Republican nomination should Boyle become sheriff, but said that he had not spoken with Schaffer about running for the seat, or about who would be his successor. “If there was a grand plan, it’s beyond me,” Cilmi said.

Schaffer, who had already proposed prospective Democratic candidates in Newsday, denied any such deal, telling the Daily News that “it would probably be a good ‘Twilight Zone’ episode.”

Boyle lost the primary to challenger Larry Zacarese in a stunning upset. The following day, Boyle said that the pledge he signed to the Republican Party was not binding, as he was no longer the nominee. Asked if Boyle could run on the Democratic line, Schaffer told Newsday, “I never foreclose any possibility.”

Months later, Schaffer denied reports he was considering giving Boyle the Democratic line after the primary. “That was never true, nor was it ever discussed between me and Phil,” he told me.

But another source recalled talking about the sheriff’s race with Schaffer and that he expressed confidence that it was “all Boyle’s.” “When Boyle lost, he hadn't expected that,” the source said, expressing surprise that Schaffer had seemed to support Boyle. “Was Phil Boyle the best candidate on the Democratic side? I don’t think so!”

On Sept. 18, a few days after the primary, Schaffer said Toulon, a member of the Suffolk County Water Authority board, would be the Democratic nominee. Toulon replaced the existing Democratic nominee, Stuart Besen, who was nominated for a judgeship instead. Toulon later secured the Conservative and Independence Party lines, and narrowly won the general election.

This kind of wheeling and dealing hasn’t escaped scrutiny. In a May 2017 editorial before the county sheriff’s race heated up, Newsday complained that third parties “often back major-party candidates in return for help in races for judgeships, county legislature and town councils. When they’re not trading their ballot lines, the deal is to nominate a faux candidate who will not campaign and is sure to lose. Meanwhile, the snookered voter thinks there was a real choice.”

Schaffer said criticism from Newsday’s editorial board is hypocritical. “Conservatives would cross-endorse Republican candidates; it wasn’t corrupt then. But then when all of a sudden I’m able to secure the Conservative line for the DA and the sheriff this past cycle, all of sudden it’s corrupt,” he said. However, this overlooks the fact that Republicans and Conservatives are often in ideological alignment, whereas Democrats and Conservatives are not.

“I’m going to do everything I have to to get the Democrats elected, and if that means working with a particular party in a particular race, like the Conservative Party, or the Independence Party or the Working Families Party, I’m going to do that,” Schaffer said.

Two weeks before Trump was inaugurated, Suffolk County resident Liuba Grechen Shirley formed a Facebook group called “New York’s 2nd District Democrats,” which now has more than 2,500 members and sponsors local progressive activist campaigns.

The Babylon resident then began circulating petitions to get the 1,250 signatures needed to run for Babylon Town Council after Schaffer failed to put up any Democratic candidates.

Schaffer said he first met with Shirley when she told him she wanted to run for town board, and she seemed more interested in national politics.

“I said, ‘Do you have issues that you want,’ and she didn’t really get into any issues,” he said. “Because remember, all we’re going to be doing at town board are parade permits, road contracts, someone redeveloping a piece of property. If that’s your forte, then let’s talk, but to me, what you’re talking about are all federal issues.”

A source familiar with both Shirley and Schaffer said that the two actually met for the first time after Shirley organized a protest outside of Rep. Pete King’s office in February. Shirley met with Schaffer again, the source said, when she realized he was not running a Democratic candidate for a seat on the Babylon Town Council, and told him that she would be happy to run. The only candidate, Anthony Manetta, was running on the Independence, Conservative and Republican lines.

In response, Schaffer told Shirley he made a deal with Manetta four months ago. Shirley asked if she could get collect petitions and get the WFP endorsement, according to this source, and Schaffer warned that she would fail. Shirley launched a bid anyway, and began receiving calls from influential county figures urging her to reconsider.

“It was trying to prove a point that the Democratic Party should be running Democrats,” the source said about Shirley’s bid for the town board. Once Claire McKeon, who oversees the town’s youth bureau, entered the Democratic primary, Shirley dropped out. However, McKeon failed to collect enough petitions, blaming a late start and unavailable party workers. Screenshots obtained by City & State from a progressive Long Island Facebook group show that members had offered to help McKeon with her campaign and collect signatures.

Schaffer then named McKeon to run against Suffolk County Legislator Kevin McCaffrey, after a Democrat dropped out of that race. McKeon did not win that race. Manetta was ultimately elected to the Babylon town board.

“Claire was just a placeholder to make sure Rich kept his deal with the Independence, Republican and Conservative parties to keep Anthony as the person who was running without any challenger to make sure that he won,” the source said.

Shirley later decided to take on King this fall. Schaffer said that he told her the only person he would support in the congressional race was DuWayne Gregory, the presiding officer of the County Legislature who challenged King in 2016 and lost with 38 percent of the vote and was mulling whether to try again. Gregory did decide to run again, and Schaffer threw his support behind him but calls it a personal and not a party endorsement.

“He does what’s best for keeping himself in power and making deals that use party patronage that make sure certain seats are held by certain people, and he takes away the power from the voters,” the same source said.

Shirley also tussled with Schaffer over his January decision to hire Lindsay Henry, a former Babylon town councilman and an Independence Party member, as a part-time assistant town attorney. Henry had been charged with assault in September for allegedly beating his girlfriend, following a domestic assault arrest that was dismissed. Schaffer assured me that he had vetted Henry, and that he would fire him if the charges were true.

Shirley delivered a letter protesting Henry’s hiring. Schaffer told Newsday that Shirley’s actions were “politically motivated.” Schaffer then wrote a letter to Newsday, saying, “I cannot support the conviction of someone in the court of public opinion, with congressional candidate Liuba Grechen Shirley acting as judge and jury.”

The case was dismissed on March 15 after the woman did not appear in court for the third time. The special prosecutor in the case said Henry “retains his presumption of innocence.” Henry’s attorney was William Wexler.

Schaffer is also in the midst of a civil war with Bellone, the only other Democrat in the county with the political clout to rival his own.

“The biggest problem for Democrats in Suffolk is the continuing dispute between Schaffer and Bellone,” said Levy, of Hofstra University.

The once close relationship may have soured even before Bellone took office as county executive. A source familiar with Bellone’s transition at the end of 2011 said Schaffer played a key role in the process, wanting to be involved with who should be hired.

The transition team began hearing rumors about alleged misconduct by James Burke, who was being considered for Suffolk County police chief. Then-District Attorney Spota had a close relationship with Burke, and wrote a letter vouching for him.

The source said that letter was sent to Schaffer for him to distribute to the transition team. Schaffer forwarded the letter to members of the Bellone transition, including Bellone. However, when Newsday reported on the letter in 2016, Schaffer told the paper that he did not recall ever receiving it.

Burke resigned as police chief in 2015, and was arrested on federal charges of attempting to cover up his assault of a handcuffed suspect. He pleaded guilty in 2016 and was sentenced to 46 months in prison. Spota was indicted in late 2017 for allegedly covering up Burke’s crime, but Schaffer never renounced his support of the district attorney.

The friendship between Schaffer and Spota had been forged in another Suffolk power struggle. In 1997, then-District Attorney James Catterson indicted five Schaffer aides in Babylon on charges of filing false documents to hide a budget deficit. Four of the aides were cleared in 1998. In 2001, Schaffer, as the new county Democratic chairman, spearheaded the effort to take down Catterson. Spota challenged Catterson and won.

Despite rumors, Schaffer denied that he had any influence over Spota. He said one of the new district attorney’s first decisions was keeping Christopher McPartland, who had worked on the Babylon case, in the district attorney’s office. McPartland became the chief of Spota’s public corruption unit, and was later indicted as well.

In 2016, The New York Times reported that the federal investigation into Burke’s activity had widened to include Spota’s office. Bellone called on Spota to resign in 2016. But Schaffer said that he did not believe Spota should step down. Even after Spota was charged, Schaffer did not join the drumbeat of resignation calls. Spota eventually stepped down on Nov. 10, but Schaffer maintained his support. “I love him, and I always will,” Schaffer told Newsday.

When Schaffer first explained his relationship with Spota to me, he used the Catterson case as a frame of reference. “Everyone told me, ‘You should fire them, get rid of them.’ And I said, ‘No, because they’ve told me they’ve not done anything wrong,’” Schaffer said of his indicted aides.

Loyalty, it seems, is the one thing more important than winning to Schaffer. Spota, Schaffer said, was “ill-served by people on his staff.” Schaffer later told me that he was talking to Spota “all the time now,” although as a friend, not a lawyer.

Rich Schaffer is charming and doesn’t seem to take himself too seriously, often dropping in a self-deprecating aside. Like many native Long Islanders, he talks with his hands and will take the most meandering route possible to get to his point when telling a story.

When Schaffer was orchestrating his endorsement of Cuomo for attorney general, everyone believed that the man likely to be elected governor, Eliot Spitzer, would choose Schaffer as state Democratic Party chairman.

“Richie is very much a Suffolk County guy. He doesn’t even like driving into Nassau County if he can help it,” Law said. Schaffer told me that Spitzer, former Gov. David Paterson and Cuomo had each asked him to lead the state Democratic Party, and he had turned them down.

“I guess I’m a homebody,” Schaffer said. It was one of the phrases he used repeatedly to describe himself, including “kumbaya kind of guy” and “therapist-in-chief.”

While referring to his political outlook as “kumbaya” raises eyebrows, “homebody” is not up for debate. Schaffer dedicates his life to his town and county. Babylon and Suffolk are focal points of critical local, state and federal elections – and of corruption cases involving public officials. At the center of it all is Schaffer, choosing candidates, and forging and breaking alliances.

The boy who traded political work for pizza has made a life and a career of it, and created a fiefdom from the large town and state-sized county he oversees.

Yet his approach could backfire. Besides Croci, four more Republican state senators are opting not to run for re-election. Cuomo brokered a truce this spring in which the IDC disbanded and ended its power-sharing agreement with the GOP. Felder is under pressure to rejoin the fold as well or face a robust primary challenge, and the governor is rumored to be seeking strong Democratic candidates to take out Boyle and pick up Croci’s seat as well. In the end, the party could finally win the state Senate, with or without Schaffer.

The second time I interviewed Schaffer, we met in his political office – his former law office. Schaffer is aware of what people say and believe about him. While standing for a photo shoot, he joked that people would be drawing devil’s horns on his head. But he also takes pride in serving his community, where he is beloved by many. Back at the North Babylon Delicatessen, Schaffer told me that he walks a fine line as a Democrat in Suffolk County.

“As Democrats, that’s the wire we walk, with trying to push our candidates locally, while at the same time not fall into the trap of getting ourselves labeled city Democrats or Washington Democrats. We have to stay true to what we’ve done here,” he said. “It makes it that much harder than doing it anywhere else.”

Correction: An earlier version of this post gave the incorrect age for Steven Dellavecchia. He is 24, not 26.

NEXT STORY: Being Mexican in NYC with Carlos Menchaca