After pouring more than a billion dollars into a series of piecemeal initiatives that failed to stem the tide of homelessness, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio made a major policy pivot. With a record 62,435 people living in city shelters as of February, the mayor announced his administration would open 90 new homeless shelters, expand 30 existing shelters and phase out the use of 360 hotels and privately-owned cluster apartment sites that house homeless families.

But when it comes to solving the puzzle of homelessness in New York City, the more things change, the more they appear to stay the same.

The contours of de Blasio’s plan is strikingly similar to the shelter siting plan that former Mayor Ed Koch started in the mid-to-late 1980s, and that his successor David Dinkins tried but failed to execute – an effort to reshape the footprint of the shelter system by building 20 to 30 new facilities and phasing out welfare hotels. The current initiative is on a much larger scale, and is ambitious enough to reset the city’s entire approach to housing the homeless and to homeless prevention. The current administration will also try to thread a tricky needle by keeping homeless people in the communities where they lived before entering the shelter system while also distributing shelters proportionally across the city – perhaps the most striking departure from the Dinkins and Koch plans.

RELATED: Landlords exploit loophole to raise rents despite freeze

At the center of the debate, once again, is Steven Banks. As the social services commissioner, Banks is tasked with carrying out the city’s new policy. Previously one of the city’s foremost homeless advocates, he has seen every administration since Koch’s fail to get a solid handle on the city’s homeless problem.

As the homeless population mushroomed under Koch, Banks became a vocal critic of the administration’s slapdash creation of the city’s shelter system – a response to the landmark 1981 Callahan v. Carey consent decree that initially enshrined the right to shelter. The court case forced the city to scramble to find shelter sites, such as city- and state-owned armories and buildings – often with little or no community notice – and worry about implementation later.

Koch launched his landmark affordable housing program in 1986, resulting in significant reductions in New York City’s homeless population and creating 15,000 housing units for homeless people. But Banks continued to rail against the administration for cramming homeless individuals in barracks-style shelters or welfare hotels with substandard living conditions.

David Dinkins’ election in 1989 gave advocates like Banks hope that a new mayor would provide a fresh perspective to the homelessness conundrum – fairly similar to when de Blasio succeeded Michael Bloomberg.

As a mayoral candidate, Dinkins slammed the Koch administration’s handling of the homelessness boom, rejecting Koch’s plan to build new shelters in favor of rehabilitating vacant apartments for homeless families – seemingly a direct response to Banks’ continuous push for permanent housing solutions.

“We thought the crisis was terrible at 20,000 people. What’s an acceptable size for the shelter system today?” – Nancy Wackstein, former director of the Mayor’s Office on Homelessness

But within months of taking office, Dinkins was forced to confront a homelessness crisis that had grown unwieldy. In the summer of 1990, a deluge of families entered the system, attributed to the city’s policy under the Callahan ruling of giving homeless people in welfare hotels priority for new apartments. By September 1991, the city was providing shelter for an average of 23,000 homeless people every night, leading Dinkins to tap Andrew Cuomo, a wunderkind nonprofit affordable housing developer, to head a commission tasked with developing broad solutions to solving homelessness.

But toward the end of 1992, the crisis was so bad that hundreds of homeless families were sleeping in overcrowded city intake offices waiting for shelter, leading a state Supreme Court judge to hold four city officials in contempt of court. Meanwhile, Banks was in the midst of his own legal battle against the Dinkins administration – the McCain v. Koch case – on behalf of families for whom the city had provided insufficient shelter. The case would, in many ways, shape Banks’ guiding philosophy as one of the chief architects of de Blasio’s homelessness policy. While cross-examining Jeffrey Carples, chief of staff to Cesar Perales, Dinkins’ deputy mayor for health and human services, Banks asked what it would take for New York City to comply with the city’s right to shelter mandate.

“[Carples] said, ‘A combination of prevention services, decent shelter and permanent housing,’” Banks recalled in a recent interview. “I asked him to explain his answer, and he said, ‘Well you need enough resources to prevent people coming into the system wherever possible, you need to have shelter that’s decent, and you need to have enough permanent housing so that there’s a flow in and out of the system.’

“Over the sweep of almost 40 years that I’ve been representing homeless people, first as a Legal Aid (Society) lawyer and now as commissioner of social services, the (shelter) system was built up in a very haphazard way,” Banks continued. “And unlike what Jeff Carples said so many years ago, the provision of ‘high-quality’ shelter didn’t have a guiding principle. That guiding principle now is community.”

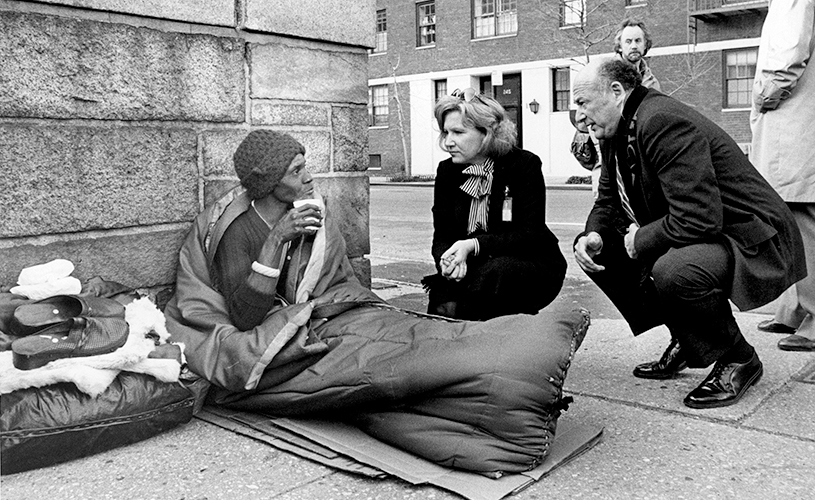

New York City Mayor Ed Koch and Jane Putnam of the Homeless Emergency Liaison Project talk to Bernice Martin on a street corner on March 23, 1983. (William E. Sauro/The New York Times/Redux)

If this tale of the Dinkins administration’s struggle managing the homelessness problem sounds familiar, it’s largely because de Blasio and Banks are still fighting similar battles – cleaning up the messes left behind by previous administrations while attempting to steer the city on a course to reduce the homeless population. Banks believes that the administration’s new policy sets the city on a course to correct Koch’s initial mistakes in setting up the shelter system – namely, not establishing a paradigm for what constitutes a quality shelter.

RELATED: Has the East New York rezoning worked?

“When I was a Legal Aid scholar back in 1981, my first clients that I represented were people who had become homeless in Staten Island and placed in the Bronx or homeless in the Bronx and placed in Staten Island,” Banks said. “And there was no guiding principle as the shelter system developed to address that problem. We’re all people that live with anchors in our lives – schools, employment, health care, houses of worship, family – and if we want to effectively give people a helping hand to get back on their feet and return to the community, either through permanent housing or reuniting with family or friends, then we have to have a guiding principle.”

The scaling back of goals in combating homelessness is a marked shift in approach for an administration that frequently sets lofty policy goals. Even de Blasio, prone to hyperbole and occasionally unrealistic ambition, was notably circumspect in evaluating his administration’s handling of the homeless problem and its modest goal to reduce the number of people living in the city’s shelter system. The city is aiming to reduce that population by 2,500 people over five years – a mere 4 percent reduction.

When de Blasio rolled out his new plan in February, he said, “Is it everything we want it to be? No. It’s the honest goal. This is what we can tell the people of New York City can be done and can be sustained.”

Much in the same way that Dinkins was a champion of homeless rights as Manhattan borough president and criticized the Koch administration’s policies, de Blasio was a fervent critic of Bloomberg’s approach to homelessness, first as a city councilman and chairman of the New York City Council’s General Welfare Committee, and later as public advocate. He notably took Bloomberg to task for his vow in 2004 to cut the city’s homeless population – at the time, roughly 38,000 – by two-thirds over five years, arguing that the mayor had failed to even acknowledge falling well short of that goal.

And while Dinkins had to deal with the shelter system mess that Koch created, with thousands of homeless families crammed in barracks-style shelters and ramshackle welfare hotels, de Blasio inherited a homeless population that had exploded under Bloomberg – 53,615 people at the time of his January 2014 inauguration. In hindsight, Bloomberg’s promise to reduce the number of homeless people living in the city was, at best, misguided, but also a victim of an unforeseen financial crisis that led the state to cut key funding for Advantage – the city’s signature rental subsidy housing program for homeless families – and subsequently forced the city to end the program entirely.

“I think a certain amount of Machiavellianism is necessary here in getting these shelters sited.” – Thomas Main, professor at Baruch College’s School of Public Affairs

But similar to the early years of Dinkins’ mayoralty – in which the city was slow to develop a comprehensive plan to combat homelessness – de Blasio moved lethargically in confronting the crisis. His deputy mayor for health and human services, Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, resigned less than two years into the job and later criticized de Blasio for not having a long-term solution. Dinkins also lost a top deputy early on when Nancy Wackstein, the director of the Mayor’s Office on Homelessness, resigned in 1991.

“We were under similar pressure (as the de Blasio administration), and we did a pretty good job of getting out of the hotels for families, opened up more NYCHA units for families, but then (the homeless population) began to creep up again,” Wackstein recalled in a recent interview. “Homelessness is a symptom of poverty. I understand that you don’t want to be in hotels and cluster sites; I think that’s right. But I don’t think even if you got 90 shelters, you’re gonna get the (homeless) number down. We thought the crisis was terrible at 20,000 people. What’s an acceptable size for the shelter system today?”

Banks, however, noted that the complexity and scope of the current homelessness crisis is far greater than anything Dinkins and Koch faced. For one thing, the face of homelessness has changed. In the ’80s and early ’90s, single adults populated many of the beds of the city’s shelter system. Currently, 70 percent of the city’s shelter system is made up of families, while 34 percent of families in the shelter system with children are headed by an adult in the workforce – a reflection of the city’s increasingly unaffordable housing stock and a local economy with a yawning equality gap. In another departure from the Dinkins and Koch era, the city has largely turned over the shelter system to nonprofit providers who, homeless advocates agree, generally do a much better job of upkeep and management.

Banks also points out that, under Koch and Dinkins, the city largely ignored homeless prevention services – an area where the de Blasio administration has increased funding by 25 percent. Previous administrations would also routinely close shelters with poor conditions without an adequate alternative in place, a policy that the de Blasio administration changed by requiring replacement capacity for any cluster site or hotel that’s closed.

Of course, that’s where the 90 new shelters come in. Perhaps the most foreboding aspect to the de Blasio administration’s new approach remains community opposition to homeless shelters – very similar to the dreaded NIMBYism that torpedoed the Koch/Dinkins plan to build 20 to 30 new shelters across the city. Before the city announced its latest policy shift, the administration had already run into a massive public outcry over plans for a new shelter site that would house about 250 homeless people in Maspeth, Queens. The string of protests culminated in an astonishing display in front of Banks’ Brooklyn home, where hundreds of protesters chanted, “Banks has gotta go!” and he was forced to call the police.

RELATED: Answering East New York's affordable housing prayers

Even in the wake of that unseemly episode and a steady pattern over the past 30 years of community resistance to shelters, Banks remains undaunted. He remembers his days as an advocate, when previous administrations opened shelters on an emergency basis in the middle of the night with no community notice. Under de Blasio, the city still will not be asking for permission from neighborhoods to host shelters, but those communities will receive 30 days’ notice and can submit public comments during that period.

“De Blasio and Dinkins made a big point of being community-based, while Koch, Giuliani and Bloomberg never sold themselves as pro-community, so nobody expected to be consulted by them,” said Thomas Main, a professor at Baruch College’s School of Public Affairs and an expert on social welfare policy. “I think a certain amount of Machiavellianism is necessary here in getting these shelters sited. The big danger is de Blasio will run into the same problems Dinkins did.”

So far, the advance notice has done little to placate communities targeted for new shelters. A men’s shelter slated to open in Crown Heights was met with a lawsuit against the city, and a Brooklyn judge recently blocked its opening to allow time for a possible compromise. If the shelter were allowed to proceed, it would be the second to open in Crown Heights, with a third set to open soon. The cluster of shelters in a single Brooklyn community begs the question of how the city will satisfy the “fair siting” aspect of its plan. Banks believes that as long as the city holds up its end of the bargain in keeping these facilities secure and seamlessly integrating them into the fabric of community, they can overcome NIMBYism. In keeping with the commitment to high-quality shelters, Banks cited a desire for new shelters to provide enough programming during the day to keep homeless men and women off the street.

“We were able to communicate to the community about things we were proposing to do that we thought would address long-standing problems there: Community outreach workers to address concerns around the shelter, enhanced NYPD presence in the area around the shelter, and, more importantly, enhanced programming within the shelter,” Banks said. “Recreational programs, counseling programs, employment-related programs that we think will help address the needs.”

Still, skeptics say that if de Blasio and Banks were truly committed to fair siting, the city’s affluent communities should also have some stake in reducing the homeless population. Others point out the inextricable link between the city’s lack of affordable housing and the boom in homelessness, and the startling absence of addressing homelessness within de Blasio’s plan to build 200,000 units of affordable housing over 10 years.

“If you’re going to build shelters in the neighborhoods from which homeless people come, what about Park Slope or the Upper West Side? If we are really one city, this may perpetuate the ‘Tale of Two Cities.’” – Nancy Wackstein, former director of the Mayor’s Office on Homelessness

“I understand the notion of community ties and children being closer to their schools, but if you’re going to build shelters in the neighborhoods from which homeless people come, what about Park Slope or the Upper West Side?” Wackstein said, suggesting that the city’s affluent neighborhoods bear some of the shelter siting burden. “If we are really one city, this may perpetuate the ‘Tale of Two Cities.’ Neighborhoods all over the city need to help solve this problem; it shouldn’t just be Brownsville and East New York and Mott Haven. The data has not changed over the years, in terms of where homeless families come from.”

There is also a sense that the city is fighting the homeless crisis with one hand tied behind its back, as it pertains to lobbying the state for assistance. Under every previous administration dating back to Dinkins, the city could count on the renewal of the NY/NY agreement, which provides a steady stream of state funding to create supportive housing for the homeless that provide on-site mental health and job training services. Yet de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo have been unable to come to an agreement on renewing the program. Instead, the de Blasio administration has committed to building 15,000 supportive housing units over the next 15 years on its own – about half the amount advocates say are needed. Meanwhile, in the recently finalized state budget, Cuomo and the state Legislature agreed to release $2.5 billion in funds that will help fund 6,000 units of supportive housing units throughout the state. It’s unclear how many of those units will be built in New York City.

“I was surprised when de Blasio put out his plan that it didn’t mention NY/NY,” said Norman Steisel, first deputy mayor in the Dinkins administration who helped negotiate the original NY/NY agreement between Dinkins and Cuomo’s father, former Gov. Mario Cuomo. “I couldn’t believe that.”

Banks countered that the absence of a NY/NY agreement would not hamper the city’s efforts, and that the city had to move swiftly in order to start construction on the new supportive housing units.

“We can’t wait. We’re going to announce our 15,000 units, and in fact, we have our first 550 units opening this year and then we’re on a trajectory to keep opening units as we proceed over the course of the plan.”

Left: New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and Human Resources Administration Coordinator Steven Banks participate in homeless outreach in February, 2016. (Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photograpghy Office) Right: Residents of Maspeth, Queens stand outside Steven Bank's Brooklyn home in October to protest a proposed homeless shelter in their neighborhood. (Sarina Trangle)

It’s easy to look at where other city administrations failed to contain homelessness and conclude that a similar fate awaits de Blasio and Banks. Koch and Dinkins’ best laid plans were hampered by a crippled economy and community backlash. Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani brought a paternalistic, “get tough” philosophy, including work requirements for shelter stays, that failed to appreciably bring the homeless population down. Bloomberg was deluded by unsustainable goals and another brutal recession.

And with de Blasio announcing his homeless policy pivot in the months leading up to his re-election campaign – while also setting his sights on growing the city’s economy, keeping crime low and achieving his affordable housing goals – it’s clear the onus will fall on Banks to make sure the groundwork is laid for a possible second term to set the city on the right track. While social welfare experts like Thomas Main assert that “nobody on the planet knows homeless policy like Steve Banks,” the former advocate now has to deal with a potential political cost to his boss and his own sterling reputation.

“There are costs that have to be weighed in light of all the priorities in terms of what a mayor needs to tackle,” Steisel said. “In some ways advocates like Banks are all the same; political cost is rarely an issue to them. He was strong in what he did (on homelessness), taking us to court on several occasions. But despite this history and his attitude and philosophy, he’s also got to deal with this very complicated balancing act, because now he’s the guy in charge.”

Still, even in the face of a seemingly unsolvable crisis, Banks is unflinching in his determination to learn from his experience as an advocate, including applying some of the lessons he learned from grilling former Dinkins administration officials during heated litigation.

“In the major areas that Jeff Carples talked about – prevention, decent shelter and permanent housing – the lessons of those periods are reflected in a very different approach,” Banks said. “All of the things I thought were important, I’m now getting an opportunity under a mayor who actually believes in these things, to implement the very programs that I brought lawsuits to try to require the government to put in place.”