New York State

Assembly Member Anna Kelles talks about how the cryptomining moratorium victory came together

Late pressure from small-business groups and the bill’s narrow scope led to it getting signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul.

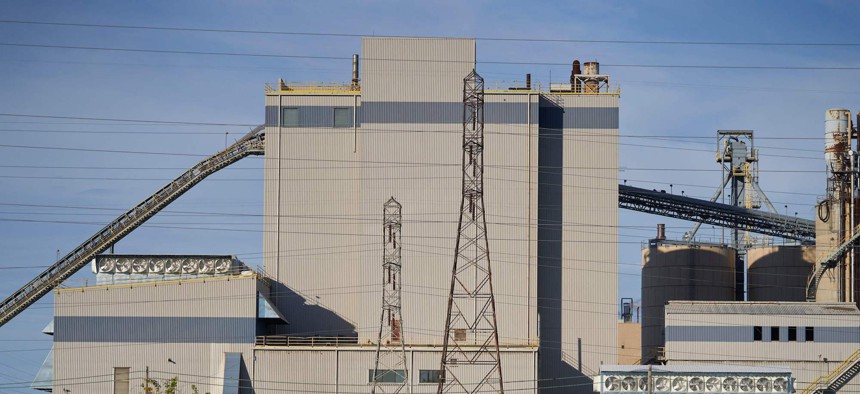

Blockfusion’s cryptomining facility in Niagara Falls was issued a cease-and-desist letter by the city in October due to local permitting issues. Geoff Robins/AFP via Getty Images

Last week, New York became the first state to implement a moratorium on a particular kind of energy-intensive cryptocurrency mining at fossil fuel plants – a technique involving thousands of computers racing to unlock new digital currencies like Bitcoin.

It was a landmark victory for environmentalists and other activists who supported the moratorium. But Assembly Member Anna Kelles, a sponsor of the bill and one of its most vocal proponents, was still insistent that this milestone legislation was actually quite narrow in scope. “This bill, all it does is put a two-year pause on the purchasing of power plants that are fossil fuel-based for the purposes of corporate cryptocurrency mining,” Kelles told City & State on Tuesday. The bill specifically targeted proof-of-work mining, which companies have deployed at old factories and power plants across the state. It also required the Department of Environmental Conservation to conduct an environmental review of proof-of-work mining.

Gov. Kathy Hochul signed the bill a week ago without any amendments – an outcome that was far from guaranteed given her relative silence on the issue since the legislation passed in June, and the consistent advocacy on the part of the cryptocurrency industry to veto the bill. Earlier this year, New York City Mayor Eric Adams had also said he would ask her to veto it.

A week after the moratorium won Hochul’s final approval, City & State caught up with Kelles to discuss how that victory happened and what comes next. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This bill was finally signed last week, but it seemed like the governor was keeping her cards pretty close to the vest about which way she would go. At what point did you know that she was leaning toward signing it?

I couldn’t imagine her ever not signing it because the bill was so pragmatic. It was very focused. It was narrow. It created a pathway to both protect our environment and protect our environmental laws, while simultaneously creating a mechanism to not completely prevent the maturing of the industry and interaction with the industry. In my interactions with (Hochul), I knew at least her executive staff and she respected and understood that (the bill) was well thought through and that it was nuanced. What she said up until the couple days before she actually signed was, “I am looking at it very carefully.” So I knew that the attention that was being given to that bill very closely coincided with how adamant the environmental community and small-business community was publicly about her signing that bill. That was a very strong influence. So to answer your question, probably a couple of days before she signed it, it started becoming clearer because of the questions that they were asking.

What do you mean by the questions they were asking?

You know, who exactly is this going to impact? What are the comprehensive environmental groups that support it? Really asking for that documentation of where the support is, who the advocates were, so that they could get a solid picture of the landscape of where the support was for the bill.

And this was the governor’s office asking these questions?

Yeah. The reason that they wanted to understand it, and I appreciate it, is because there had been a huge outcry from the small-business community over the last couple of months. The comprehensive outreach from the small-business community, I think, in the last six months, was a new push. There had been a lot of small businesses that started to really formally coalesce over the last six months once the bill passed the Senate and the Assembly. And I think that they took that seriously. Because the argument from the industry was that this was bad for business. But if the governor was hearing from a lot of small businesses that they supported this piece of legislation because they were experiencing negative impacts of the large-scale corporate cryptocurrency mining, then it really creates a counternarrative to what the industry was saying. And I appreciated that they were taking that very seriously.

This law won’t stop existing proof-of-work mining operations, but it will pause new or renewed licenses for fossil fuel-burning plants using power being produced on site for proof-of-work mining. Do you have a sense of how much of a difference this is going to make in terms of environmental effects? How many new mining operations might have set up shop in New York over the next two years if not for this law?

If you look at the trend, just in the last couple of years, of purchasing power plants across the country – Greenidge Generation was the first, but it really took off from that point – it shows that it was a model that really drew businesses. And if you understand cryptocurrency mining – consolidated cryptocurrency mining, meaning corporate cryptocurrency mining – the single greatest expense is the electricity cost. So it makes total sense that some of the cheapest energy that they could get is the energy they could make themselves, because they don’t have to purchase it from the grid. That was why it took off once the model was established. And we have 40 retired power plants in New York state. Once Greenidge took off, the North Tonawanda facility was already pursuing this certificate from the Public Service Commission to put a cryptocurrency mining operation (there). So the risk was too high. Because once the operations are established in these facilities, they are instantly adding millions of tons, collectively, of greenhouse gas emissions to our portfolio of how much greenhouse gases are being emitted by New York state, which is already very high. If you look at our Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, it’s not just an aspirational goal, it is established into law that by 2050, we will have net-zero emissions. And the question is, if we had let this take over like wildfire across all of our power plants that are currently sitting mothballed, would we be able to reach our climate goals? And my concern is that we would not.

The law also requires a generic environmental impact statement review of proof-of-work mining. What do you hope to come out of the study or learn from it?

The question is, what are the environmental impacts of proof-of-work-based cryptocurrency mining (and) its impact on air quality, water quality and greenhouse gas emissions? And what is its impact on our ability to reach our CLCPA goals? That is what we’re looking for. So that could look like many things. An evaluation of the industry, not only of its current state, but the increase over time. If there were no regulation, how much increase would we continue to see? And what is the concurrent amount of increase in energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions that we can expect to see with the current trend of an increase in cryptocurrency mining in the state? And there’s a couple things that we would need to understand. Is it going to increase the taxing of our current electric grid? Will we have to significantly increase how much renewable energy infrastructure we will have to build in order to meet our CLCPA goals with the increase in baseload demand specifically associated with cryptocurrency mining?

Some in the crypto and tech industries have made the argument that this moratorium will send an unfriendly message about New York’s openness to these emerging industries. What’s your response to that?

I think that’s ridiculous. Anytime that there is any kind of law that might demand information or data or facts on the impact of an industry or even regulate industry, the knee-jerk, baseline, instantaneous rhetoric that we hear from industry is, “You can’t do this because this will negatively impact innovation and business.” This bill, all it does is put a two-year pause on the purchasing of power plants that are fossil fuel-based for the purposes of corporate cryptocurrency mining. That is exclusively all it does. It does not put a pause on cryptocurrency mining that uses renewable energy infrastructure. So you could say that, in fact, this bill could inspire innovation. Because what it says is, we will not put a pause on you if you figure out a way to be exclusively on renewable energy infrastructure. And even more importantly, if you are on renewable energy infrastructure that is on-site, meaning where the cryptocurrency mining is happening, then you won’t even impact the grid, and therefore you may not have any impact on our future ability to reach our climate goals. So I think that the truth is that this bill will actually spur innovation. If people want to continue to do cryptocurrency mining, then they have to innovate.

What do you foresee happening after two years, when this moratorium expires? Will you look at extending it further or look at an outright ban on new permits for this particular method of mining?

My hope is in two years we will have the (general environmental impact statement) that will give us the data so that any decisions we make moving forward will be data driven, not rhetoric. And I trust our Department of Environmental Conservation because not only are they experts, not only have they proven themselves to be able to do this – they’ve done very thorough processes in the past – the process itself is transparent. It requires that they submit a draft GEIS to the public, that there is a public comment review period, and that they then review all of that public comment and they incorporate it into their final draft. It is comprehensive, it is transparent and it is done by our state experts. And once we have that data, we can have a conversation moving forward that is data driven to ensure that we are able to reach our CLCPA goals, which again I will reiterate, is law, it’s not aspirational. That is our duty as a state.