Education

Specialized high schools and race

Will New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to eliminate the entrance exam make education more fair for minorities?

Mayor Bill de Blasio announces his plan to revise the admissions process for New York City's specialized high schools. Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office

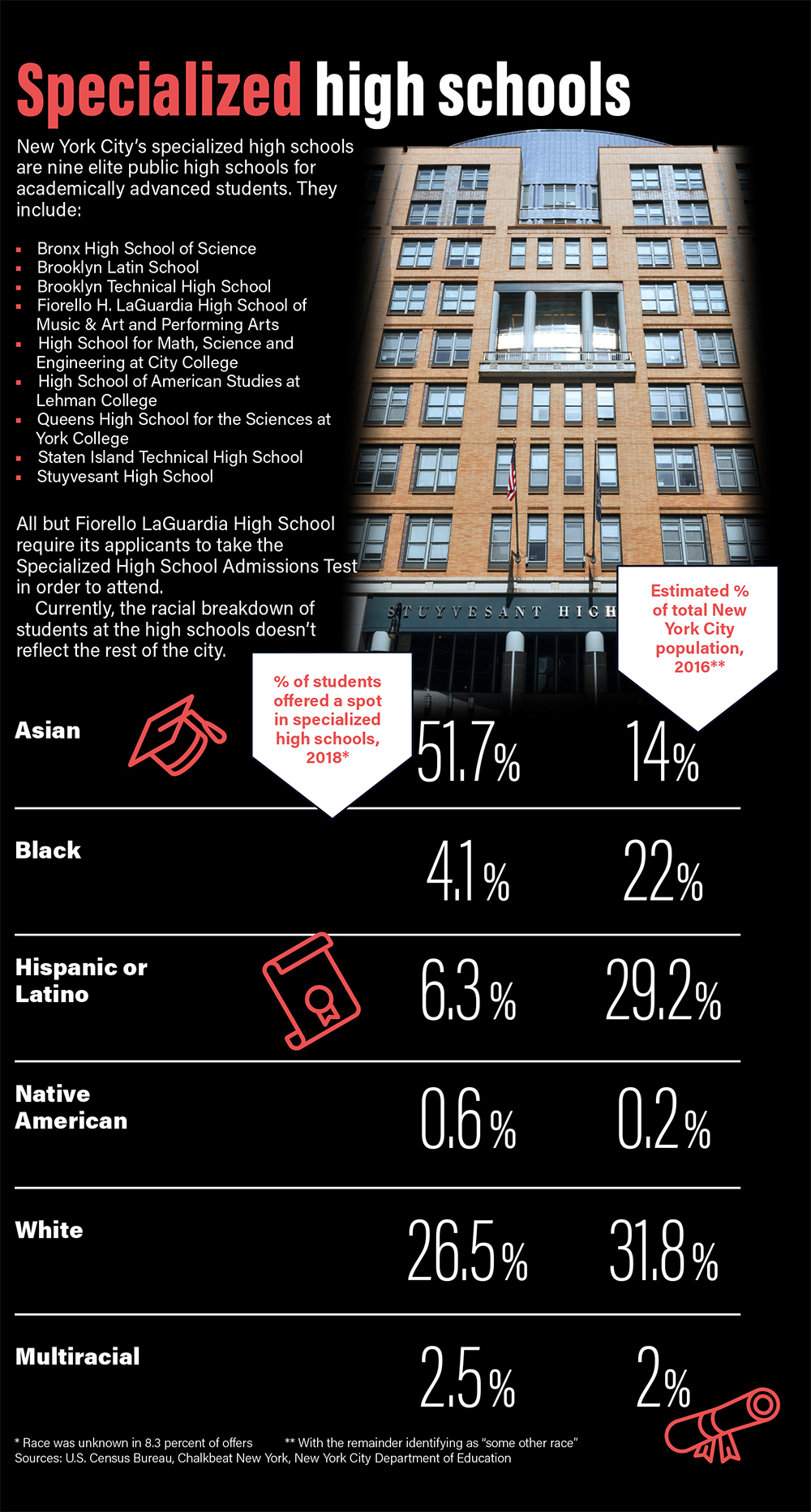

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio made waves in June when he called on state lawmakers to eliminate the city’s Specialized High School Admissions Test, or SHSAT, in order to increase diversity in those top schools. The proposal prompted immediate backlash from alumni, who defended the test, and from Asian-American groups, who called the proposal discriminatory against them.

The debate has been raging ever since – and it can’t be resolved until next year.

In order to eliminate the test, de Blasio would need legislative approval in Albany, and he worked with Assemblyman Charles Barron to introduce a bill. Although versions of the bill had been introduced in previous sessions, this is the first time it would scrap the test altogether. In previous years, legislative proposals would have added more criteria to be considered for admission to those schools, in addition to the test. Those bills never made it out of the education committees in the state Senate and Assembly, thanks in part to the very same groups protesting the current proposal.

This year’s bill did manage to make it out of the Assembly Education Committee, although Speaker Carl Heastie said in early June that it would not be taken up by the full chamber until 2019, allowing time to study the proposal and get input from “all of the stakeholders.”

Barron said the support to make changes to the specialized high school admission process has been growing, including from alumni, which allowed his legislation to go further than it ever has this year, even with more radical proposed changes.

“That is just a racist notion that because of the school not being a top performing school, that the individual students in those schools cannot be top performing students.” – Assemblyman Charles Barron

In place of the test, the top 7 percent of students at every middle school in the city would be admitted to the eight elite city high schools. This excludes Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, which accepts students based on auditions. This way, all schools become so-called “feeder schools,” rather than the majority of students coming from a small percentage of middle schools. “I think this is the right way to go,” Barron said. “It’s equal access. No one has an advantage.”

According to New York City Department of Education spokesman Will Mantell, the citywide average GPA of students in the top 7 percent of their classes is 94 out of 100, the same average GPA of students offered a spot at the elite high schools. Additionally, he said their state test scores are comparable, an average of 3.9 out of 4.5 for the top 7 percent versus 4.1 for those admitted to the specialized high schools.

Proponents of keeping the test have said it is the most objective way to measure performance and including other criteria could weaken the schools.

“That is just a racist notion that because of the school not being a top performing school as some of the other schools, that the individual students in those schools cannot be top performing students,” Barron said.

However, Assemblyman Ron Kim, one of only two Asian-American members of the Assembly and one of the dissenting votes in the Education Committee vote, said de Blasio’s announcement was made far too abruptly and failed to incorporate input from the Asian-American community in a plan the mayor claims will increase diversity. Currently, Asian-American students make up about 62 percent of the elite schools, even though they make up just 16 percent of the city’s public school population.

“I think racially balancing a few schools doesn’t translate to racial equality,” Kim said. “When you really want to fight for racial equality in the public schools, you try to expand the pie for all minorities and don’t just pit one group against another in hopes to get some headlines in the paper.”

Kim said he supports finding ways to improve the testing and ensuring that admitted students measure up to the best standards, but that was not what de Blasio had in mind.

“This had nothing to do with improving the test. This was about race and racial integration and about racial equality,” Kim said. “You can’t have it both. … Those are two entirely different paradigms of conversation.”

“When you really want to fight for racial equality in the public schools, you try to expand the pie for all minorities and don’t just pit one group against another.” – Assemblyman Ron Kim

The other part of the mayor’s plan to diversify the elite high schools has stirred up far less controversy and does not require state approval. De Blasio plans to expand the Discovery program, which offers seats to underprivileged students who just missed the cutoff score on the admission test, provided they take a three-week course. Currently, about 5 percent of seats are filled this way. The expansion would increase the number to 20 percent by 2020.

De Blasio’s plan is not the only proposal aimed at expanding opportunity. Another bill has been sitting in the state Legislature for years to create a pre-SHSAT exam, much like a pre-SAT, to help prepare students for the test. More recently, state Sen. Tony Avella, a supporter of the SHSAT, introduced legislation in July to expand gifted and talented programs from elementary schools into middle schools in each school district. His logic is that by adding resources in middle schools, more students would have the tools to pass the test.

“First of all, I know students who come from a gifted and talented school called Philippa Schuyler. Many of them are brilliant students who didn’t pass the test, even though they had a gifted and talented school in itself,” Barron said. “Tony Avella isn’t coming up with anything new. Those things already exist. And even if you expanded on them, the results will be the same.”

However, there is some evidence to support Avella’s approach. According to a report in The Atlantic, the percentage of black and Latino students at specialized high schools was much higher when honors programs were more commonplace across the city. The city largely eliminated these so-called tracking programs in the 1990s, and the number of black and Latino kids at the schools dramatically fell.

Taking the place of intraschool tracking, which puts high-achieving students on a more academically challenging path within the school, are competitively screened schools. Tracking still occurs, only it happens between schools. So high-achieving students gravitate to a small number of schools, increasing segregation as local schools fail to attract talent and resources. There is some debate whether gifted and talented programs are part of the problem – since a single test also determines whether a student qualifies – or the solution to the city’s school segregation problem, and whether or not they are fair.

“I don’t believe in this specialized, elitist strata in the first place. I’m trying to make the best of a bad situation,” Barron said. “I think all students are special, all schools should be special.”

NEXT STORY: Simcha Felder’s outsized impact on education