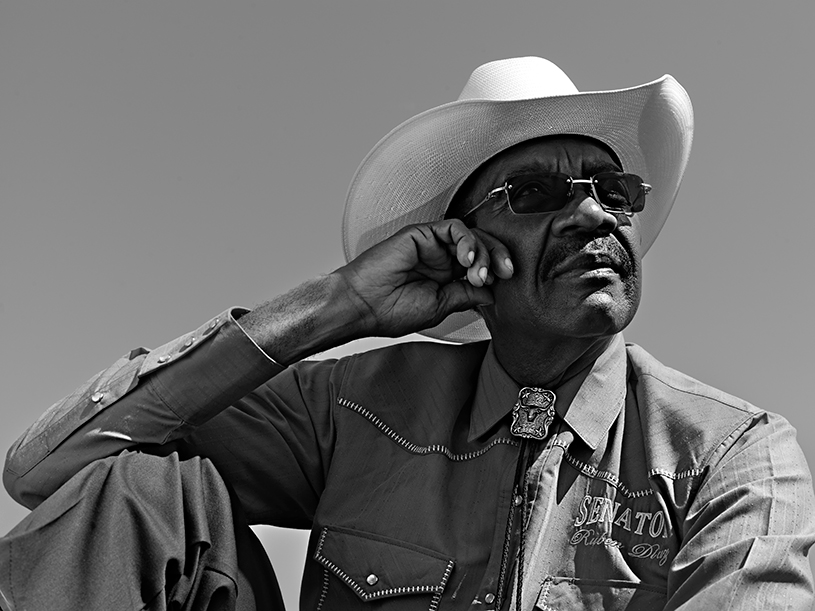

One of the first things I notice when walking through state Sen. Rubén Díaz Sr.’s South Bronx district headquarters is a wooden sign adorning the entrance of his office with the word “COWBOY” in big, bold letters. It’s a fitting introduction to a man who likens himself to a political gunslinger in New York City and state politics. And based on his sartorial choices at least, Díaz fits the bill.

Sitting behind his desk, Díaz wears a checked grey suit with a black cowboy hat resting on top of his thinning hair, a black shirt and a silver bolo tie around his neck, with gold-rimmed glasses framing his face. If you didn’t know any better, you might think this titan of Bronx politics was auditioning for a role in “True Grit.”

Yet Díaz’s fashion sense is only one small piece of what makes him such a complicated and enigmatic figure in New York government. Since bursting on the political scene in the 1980s and attempting to break down the door of the Bronx County Democratic machine, Díaz has made a habit of bucking conventional wisdom and political tact. His more than two decades in government has had its fair share of peaks – including 18 bills that have made it to the governor’s desk over the course of his 13 years in the state Legislature, 16 of which were signed into law – but has also been punctuated by Díaz’s opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion rights, social views that cut sharply against the grain of New York City’s progressive reputation.

Depending on whom you speak to, Díaz is an unrepentant homophobe, a benevolent man of God who lives by a strict dogmatic code, a narcissistic headache for the New York Democratic establishment or a deeply popular local politician who delivers some of the best constituent services in the borough. Or, perhaps, all of the above.

RELATED: Ranking all of the New York City Council members

So why, after nearly 15 years of stirring the pot in Albany, is the 74-year-old preparing for what, in all likelihood, would be the final chapter of his political career – a return to the New York City Council, where he first entered political office in 2001? Already, members of the overwhelmingly liberal legislative body have signaled their resistance to Díaz’s brand of social conservatism.

Jimmy Van Bramer, one of several openly gay City Council members who would serve alongside Díaz if he’s successful in the September Democratic primary, said, “We are, as a council, extremely pro-LGBT. We are very pro-choice, vehemently defending a woman’s right to choose. I don’t want to see the council as a body become much more conservative. I don’t want to see it become populated with many more folks who are anti-choice or anti-equality.” New York City Public Advocate Letitia James, who often presides over council meetings, told the Gay City News that Díaz “has no place in the New York City Council or any other elected office.”

For Díaz, these statements are emblematic of the battles he is increasingly trying to shy away from. Those close to Díaz like to say he lives by the moral code, “hate the sin, love the sinner,” an ironic credo given that Díaz’s past offensive statements on reproductive or LGBT rights have overshadowed his legislative accomplishments.

“It’s not who you are, it’s what you do,” Díaz tells me at one point during an hourslong conversation one summer afternoon. “It’s not about what you believe or what’s your agenda. It’s who you are, and I think that I’ve proven that to the community. Political pressure doesn’t affect me, and I do what I want to do. I create jobs and housing in the best district in the Bronx. I think I can do even better in City Hall.”

Díaz opens our conversation with an anecdote about an event from his youth that drastically hardened his worldview. He was born and raised in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, the second-largest city on the island, where blacks like Díaz are a minority. While ethnic tensions between white and black Puerto Ricans have become more acute in recent years, Díaz was blissfully unaware of such strife until he joined the U.S. Army in 1960 at 18 years old and shipped off to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for basic training.

The first time he was allowed a weekend pass to leave the base, which sits on the outskirts of Columbia, Díaz and several Army friends, all Puerto Rican, went out to a bar in the city. As Díaz describes it, his friends were light-skinned and could pass for white. A waiter approached their table, took his friends’ drink orders and promptly turned his back on Díaz.

“So I called, ‘Hey waiter, I want a beer too,’” Díaz recalled. “I’ll never forget his voice, he said, ‘Whatever you’re looking for, we haven’t got it.’ My English wasn’t good so I asked my friend, ‘What did he say?’ He said, ‘You have to go because he wouldn’t serve you.’ So they stood there, all my Puerto Rican friends stood there, and they asked me to leave and I had to leave the bar.”

“Political pressure doesn’t affect me, and I do what I want to do. I create jobs and housing in the best district in the Bronx. I think I can do even better in City Hall.”

The incident led to a downward spiral. After being honorably discharged from the Army, he settled in Brooklyn, where drug addiction took hold. Díaz is evasive on this chapter of his biography, unwilling to give many details about his “problems,” but news reports indicate that he pleaded guilty to charges of heroin and marijuana possession in 1965 and was put on probation.

Then, Díaz found salvation in the church. His path to piety began with what he describes as an instance of divine intervention. A close friend overdosed, lost consciousness and was presumed to be dead. Rather than go to a hospital, Díaz and others brought his body to a Pentecostal church in Brooklyn. “The church prayed for him, and he came back to life,” Díaz said. “So since that time, I've been serving the Lord. I don't smoke, I don't drink, I don't dance. Since the beginning of 1966, I have been a new person.”

In 1977, Díaz opened his first senior center, Christian Community in Action. Relying on an influx of city funding in subsequent years from Mayor Ed Koch – who, Bronx insiders say, was looking for an alternative social services conduit other than Ramon Velez, the borough’s famed “poverty pimp” – Díaz opened several other senior centers across the Bronx in the 1980s.

He also became an ordained minister and opened his own Pentecostal church, Christian Community Neighborhood Church with a modest congregation of 60 to 70 people.

Most pentecostals adhere to the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, not quite the biblical literalism espoused by Christian fundamentalists, but the belief that the Bible is without fault and should be followed as a way of life. In that context, while many of the sins listed in the Bible make little to no practical sense in modern-day society, homosexuality and abortion have persisted.

On these two issues, Díaz practices what he preaches, and it has gotten him in hot water with LGBT and pro-abortion rights New Yorkers. Politically, it has also fed Díaz’s independent streak. Díaz has never wavered from his membership to the Democratic Party, but that has not stopped him from supporting conservative candidates, including Republicans like Rudy Giuliani for mayor in 1993 and Ted Cruz for the Republican nomination for president in 2016.

In fact, it was Giuliani’s appointment of Díaz as Bronx commissioner of the Civilian Complaint Review Board in 1993 that amplified his views on homosexuality. Around that time, Díaz began penning a column for Impacto, a now-defunct Spanish-language weekly. Months before New York City was set to host the Gay Games in June 1994 – an Olympics-style sporting event for LGBT athletes – Díaz wrote that the 20,000 competing athletes “are likely to be already infected with AIDS or can return home with the virus,” and warned that the city hosting the games would send the wrong message to children.

The column created a firestorm, with then-City Councilman Thomas Duane and others pressuring Díaz to resign from the CCRB. While he initially refused to apologize, attributing his comments to his religious beliefs, with some distance he now regrets those remarks.

“I understand the gay community feeling hurt,” Díaz said. “I got my brother, my niece, my granddaughter, many family who are gay, I don't hate them. I go out with (longtime attorney) Christopher Lynn and his partner. I’m taking Christopher Lynn with me to the City Council as my lawyer.”

My first instinct was to view this response as a classic use of the “some of my best friends are (gay, black, Latino, etc.)” trope that some lean on to mask their personal prejudices, so I reached out to several openly gay elected officials and friends who have dealt with Díaz in a professional and personal capacity to try and pierce through that notion.

Lynn, an openly gay former CCRB commissioner from Manhattan and later Giuliani’s transportation commissioner, has seen the good, bad and ugly version of Díaz during their two decades of friendship. I asked Lynn how he could remain friends with him.

“He has a system of religious beliefs,” Lynn said. “I’ve got to laugh at him and say, ‘What? You believe in the book of Revelation?’ And he does! And he believes in the end of time! So what? How does that translate? If he sees someone laying on the sidewalk, he’s not going to step over them, he’s going to help them. … But I know too many people who are absolutely liberal like me but won’t give a coin to a beggar. So he doesn’t deny my humanity.”

RELATED: Why is it still so hard to come out in New York politics?

Ritchie Torres, an openly gay City Councilman from the Bronx and a council speaker candidate, said that while he and Díaz disagree on social issues, that has not prevented them from working together.

“You can have profound differences of opinion with him, but no one can deny the high standard of visibility and constituent services in his district,” Torres said. “I will collaborate with everyone, including those with whom I have differences of opinion. I have business owners on Arthur Avenue who are Trump supporters, but I continue to work with them. That is the nature of governance in a politically pluralistic world.”

Torres adds: “Why am I going to wage war on those issues when I have already won? I, as a gay man, can get married. I’d rather focus on the areas where we agree.”

Even Duane, the openly gay former legislator who painted Díaz as homophobic and led the charge to oust him from the CCRB, had a change of heart when they served together in the state Senate, becoming quite friendly with Díaz. In fact, Díaz said it was Duane who introduced him to City Councilman Corey Johnson, another openly gay speaker candidate who is also HIV-positive, while Díaz was recovering from major back surgery last year. Johnson did not respond to requests for comment on his relationship with Díaz. Duane was on vacation and could not be reached for comment, but he had his assistant forward me one of Díaz’s famed “What You Should Know” emails, in which he cited Duane’s “high level of human dignity” following his 2012 retirement announcement. Notably, Díaz heaped praise on Duane’s decision to vote against one of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s state budget bills, which, Díaz contended, was damaging to black and Latino communities. (Díaz typically is a lone protest vote against the budget.)

Díaz doesn’t talk much about his gay family members – one gay brother lives in Puerto Rico and his other gay brother died – but he and his granddaughter, Erica, who is lesbian, made headlines in 2011 for dueling rallies at the Bronx courthouse on the issue of same-sex marriage. At one point Erica Díaz, a Navy veteran who was discharged after she came out to her commanding officer just before President Barack Obama repealed the “don’t ask, don’t tell” law, took to the stage to stand next to her grandfather. Díaz reportedly did not miss a beat, and embraced Erica on stage. She later told The New York Times that she “wanted him to know that I’m here, and that as long as I am alive, I’m going to stand up for what is right.”

“I am still young. I’m still full of energy. Why should I retire? I have the experience. I have the knowledge and dedication, the guts to do it.”

Erica did not respond to a request to comment on her relationship with her grandfather. I asked Díaz’s son, Rubén Jr., the Bronx borough president, how his father interacts with his gay family members given his views on homosexuality.

“The way he comports himself with his brothers, the way he is with his granddaughter, it doesn’t even come up (as an issue),” Díaz Jr. said. “It’s not like he treats the other grandchildren with more favoritism. I think it’s the opposite. I think he shows Erica, because she’s the oldest, there’s a certain adult level of conversation that he has with Erica, especially when it comes to her love life. It’s cute, it’s comical, it’s funny, it’s loving. It’s not even an issue. There’s nothing but love when it comes to that relationship and when it comes to him and his gay brothers.”

Díaz Jr. also points out that his father struggles with his command of English, which he claims comes into play when he makes controversial statements. Indeed, Díaz Sr. speaks in halting English, further obscured by his deep, gravelly voice.

“Being born and raised in Puerto Rico, his thought process is in Spanish,” Díaz Jr. said. “If you know a little bit about Puerto Ricans and Latinos, a lot of times we express ourselves metaphorically. Sometimes with those sayings, he tries to translate them and they don’t always translate correctly in English, so he translates them verbatim and people are going to take him literally. Sometimes I know what he’s trying to convey but it sounds brash because some of it gets lost in translation. Other times, I always say be careful how you say it.”

These interviews paint a far more complicated picture of Díaz Sr. than the common perception that he is a homophobe. But it’s also clear that Díaz remains steadfast in his positions, disconnected from the progressive trajectory of abortion rights and LGBT equality in the U.S. Later on in our conversation, I circle back to Díaz’s experience as a victim of discrimination in the Army to draw a comparison to how the LGBT community might perceive Díaz’s stance on homosexuality. As someone who experienced racism directly, can he relate to gay people who get offended by his past statements?

“Of course,” he responds, pausing for a beat. “I mean, if that’s the way they want to put it.”

As Díaz and I drive around his South Bronx neighborhood in his black Nissan sedan, the fruits of his labor as a legislator are clear to see: finely manicured parks, new businesses popping up left and right, and, of course, a healthy dose of the trademark Díaz vainglory – Rubén Díaz Village, Rubén Díaz Apartments, Rubén Díaz Plaza. He beams with pride at his accomplishments.

“Look at these schools, look at the streets. This is the South Bronx. This is my district! I’m so proud of what I've done,” Díaz says.

We arrive at a nondescript white brick building in the Morrisania section of his district, where Díaz’s colleagues in the Bronx Democratic Party are throwing him a fundraiser for his City Council run. The party is in a renovated loft space at the top of a steep staircase. Díaz, only a year removed from major back surgery, jokes, “This is where the rubber meets the road,” as he staggers up the staircase.

The room is filled with Bronx Democratic elected officials – Marcos Crespo, the county leader and chairman of the Assembly Puerto Rican/Hispanic Task Force; Assemblyman Luis Sepúlveda; and City Councilman Rafael Salamanca. Even Carmen Arroyo, the longtime assemblywoman who has sparred with Díaz on many occasions, greets the senator with a warm embrace.

“I think that the first one who was surprised to see me here was Rev. Díaz,” Arroyo said later in a brief speech honoring Díaz.

Indeed, the political spectrum of Bronx Democrats runs the gamut from liberal progressives to Democrats In Name Only, but it’s the organization’s code of collegiality that trumps all. It helps that many of these legislators share Puerto Rican heritage, a bond that reflects the sea change in Bronx politics over the past 30 years, from a county of mostly white Irish and Jewish politicians to the majority-minority place it is today.

It’s hard to imagine a time when the Díaz name wasn’t tethered to the Bronx County Democratic machine. But it took Díaz’s failures as a City Council and Assembly candidate in the 1980s, and, finally, his son, Rubén Jr. winning a landmark 1996 Assembly victory over another Bronx political family scion, Pedro Gautier Espada (son of then-state Sen. Pedro Espada Jr.) for the Díaz family to get a foot in the door. Díaz Sr. finally tasted victory five years after his son, winning a City Council race in 2001, before quickly turning around and running for state Senate in 2002 against Espada Jr., who had switched parties to become a Republican.

But Díaz’s history with county is complicated. He has cultivated a political network within the county organization – besides his son, the borough president, both Crespo and Sepúlveda worked in Díaz’s state Senate office before becoming legislators. Sepúlveda, in particular, sided against Díaz and a group of Bronx Democrats that moved to oust then-county boss Jose Rivera during the famed Rainbow Rebellion of 2008. Now, Sepúlveda is managing Díaz’s council campaign.

“Once he lets you in, you can’t have a better friend,” Sepúlveda said. “Him and I disagree on social issues. I get a lot of attacks, ‘Why am I supporting a conservative Democrat whose views don’t align with mine?’ I’m for same-sex marriage and for (a woman’s right to choose) – and how I respond is, you should be asking, ‘Why is a conservative Democrat supporting a liberal, progressive Democrat?’”

RELATED: Key 2017 New York City primaries by district

Still, despite a widespread respect for how well Díaz delivers constituent services, Bronx political insiders acknowledge an element of unease among his colleagues. In his speech at the fundraiser, Crespo joked, “I beg you to help me get him elected to the City Council so I can get him out of Albany,” but there may be an element of truth to that, particularly as it pertains to some of Díaz’s controversial statements and his past alliances with state Senate Republicans.

Díaz was famously a member of the “Four Amigos,” a nickname he coined, which included former state Sens. Pedro Espada, Carl Kruger and Hiram Monserrate – that broke away from Senate Democrats and caucused with Republicans in 2009. All but Díaz would end up in prison for various crimes. Díaz said the maneuver was all about creating political power, and giving a stronger voice to his constituents. The Four Amigos also planted the seed for another Democratic revolt: the current leadership arrangement between the state Senate Independent Democratic Conference, led by Bronx state Sen. Jeff Klein, and Republicans, a fact that’s not lost on Díaz.

“It was too big for us Hispanics to get the power,” he said. “But we got it, we did it. Now Jeff Klein comes with four whites and says, ‘Make me second in command, give me offices, give me this, give me that.’”

Bronx Democrats also have their eye trained on the 2021 mayoral race, when Díaz Jr. is widely expected to run in an open election that may be their best shot at Gracie Mansion since Fernando Ferrer challenged Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2005.

Díaz Sr. seemed genuinely conflicted about whether he views himself as a political liability for his son – “I don't know, maybe I am” – and knows Díaz Jr. is, at times, asked to answer for his father’s statements and actions. Publicly, Díaz Jr. takes the comparison in stride, although he supports LGBT and abortion rights. He is his father’s son and he doesn’t run away from it.

“I’ve been (an elected official) now over 20 years. I’m 44 years old. I think that people understand the differences between my father and I and our issues,” Díaz Jr. said. “At the dinner table when we all come together at mom’s house and you not only hear from me and dad, but our siblings and grandchildren – everybody has political differences, and we can be quite verbose about it, but we do it in a respectful way. (My father) understands where I’m coming from and so we just agree to disagree.”

Díaz Jr. is also quick to credit his father for helping secure the influx of investment coming the Bronx’s way, including four new Metro-North stations, $1.8 billion to rebuild the Sheridan Expressway and thousands of units of affordable housing. Díaz Jr. points to the bills his father passed through the state Legislature – many while Diaz was in the minority conference – as a measure of his effectiveness. He also understands why some question his father’s motives for pursuing at least another four years in elected office at age 74.

“I don’t plan on being an elected official at 74 years old, but if I was 74 years old with the record that he has in terms of delivering services and having tangible projects and legislation and bringing real change to this community over the next decade and a half, I would have called it a day,” Díaz Jr. said.

"If I was 74 years old with the record that he has in terms of delivering services and having tangible projects and legislation ... I would have called it a day.” – Bronx Borough President Rubén Díaz Jr.

Díaz Sr. bristles at that notion that he should step aside for a younger generation: “I am still young. I'm still full of energy. Why should I retire? I have the experience. I have the knowledge and dedication, the guts to do it. I still have the energy and the vision, why resign because they are young?”

Two of Díaz’s City Council opponents, Elvin Garcia and Amanda Farias, both mentioned the need for new blood and fresh ideas in Bronx politics, rather than the county party propping up machine candidates. The Bronx Democratic Party, like most county parties in New York City, is a vestige of Tammany Hall-style politics – famously resistant to outsiders that don’t have a built-in base of support or major fundraising connections.

In a revealing moment, Arroyo said as much at the fundraiser for Díaz: “We cannot allow people to come from the outside to take over the work that we developed without the contacts that are necessary to bring money to the South Bronx.”

Farias, an aide to City Councilwoman Elizabeth Crowley of Queens and manager of the City Council Women’s Caucus, said this mindset is reflective of Díaz and the county organization, and went a step further by pointing out the Bronx Democratic Party is a veritable boys’ club: Arroyo, Assemblywoman Latoya Joyner and City Councilwoman Vanessa Gibson are its only female elected legislators.

“They have a record of protecting incumbents and are always slow to adopt change,” Farias said. “Even as women have put in their time and built their own base of support, they don’t have the support of the boys’ club. There will not ever be progress if we don’t start holding the men accountable and letting them know that they need to look at women under them and start lifting them up to run as candidates and have leadership roles within their offices.”

The challenge as it pertains to Díaz is that his base of support is inherently more socially conservative. In many parts of the city, a candidate with his views on same-sex marriage and LGBT rights would be anathema. But there is a reason that Díaz has remained in office for 16 years.

Garcia, who is an openly gay Bronx borough director for Mayor Bill de Blasio, recognizes the fine line between making the race a commentary on Díaz versus focusing on the quality of life issues that the residents of the 18th City Council District care about. He has said that he does not want to make the race all about identity politics.

“At the end of the day this is a working-class community,” Garcia said. “So while there is feminist and pro-choice activism in this district, while there are openly gay couples and young people that are registered to vote in this district, people care about the reduction in crime, people care about improving the schools, access to transportation – those are the bread-and-butter issues, ultimately.”

But in the era of President Donald Trump, when political rhetoric is being scrutinized more than ever, even if Díaz remains on his best behavior, 2017 could be the year that his statements and social views come back to haunt him. Last year, Díaz was quoted in The Washington Post comparing himself favorably to Trump, and his bizarre flirtation with Ted Cruz during the Republican primary – possibly the most reviled politician in the city after his infamous “New York values” comment – might not win him any new votes in a crowded primary.

For now, Díaz has no plans to ride off into the sunset without a fight, content to rely on his base of support. He leads the field of 10 candidates in private funds raised – just under $125,000 – but trails Garcia in total cash on hand, as of the latest New York City Campaign Finance Board filing deadline. He insists that voters and his potential colleagues in the City Council not judge him based on reputation alone, but he is also going to be himself, for better or worse.

“I will talk to everybody,” he said. “I will reach everybody and I will talk to the people. People need to know me and then judge me. But people also need to give me the opportunity.”

He pauses a beat and adds a caveat: “And if they don’t even want to talk to me, and they say, ‘Get out of here,’ then I respect that.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly noted that Ruben Díaz Sr.'s Nissan sedan was state-issued; it is a private car owned by Díaz. The article also misrepresented the side Díaz took in the Rainbow Rebellion. He voted against Jose Rivera.

NEXT STORY: Winners & Losers 8/18/17