When Robert Doren, a Buffalo-based attorney, advises firms before they head into labor negotiations, he now makes sure to ask about their finances, their management goals and any vulnerabilities that could potentially embarrass the company.

“The strike of the 21st century, I would say, is the corporate campaign,” Doren said. “When the employees represented by the union continue to work, and the union attacks the company publicly … it doesn’t make any difference whether any of the allegations are truthful. By making the allegation, it damages the reputation of the company. And the company is more likely to want to agree to the union terms.”

In the wake of the Occupy Wall Street protests against bankers and wealthy elites, some point to the rise of a newer kind of private-sector strike: the demonstration strike, in which workers walk off the job for a brief period to draw attention to the case they’re pressing with their employer while trying to sway public opinion enough to force them to compromise. Think of the fast food workers who walked off the job for a day in 2012, spurring a slew of similar demonstrations, and, ultimately, the governor’s adoption of a wage board’s $15 recommended minimum wage in the fast food industry. Or consider the security personnel, baggage handlers, cleaning employees and others working for Port Authority airport contractors who have briefly abandoned their posts multiple times in a campaign that eventually resulted in unionization and negotiations for wage and benefit improvements.

These successes, in turn, have emboldened union leaders who conduct more traditional strikes, in which employees aim to get management to agree to more favorable conditions by refusing to work so long that they undercut productivity and reduce revenue.

Still, statistics show that the number of work stoppages has been steadily declining for decades. The drop in strikes and lockouts, many historians agree, can be traced to the diminished clout of organized labor once it became more acceptable to fire those on strike and hire replacement workers in the 1980s. A high unemployment rate and ease with which companies can outsource jobs also deter such actions.

During New York City’s most recent mayoral campaign, about 200 fast food workers went on strike for a day in November 2012, holding demonstrations at various restaurants and one central rally outside a Times Square McDonald’s. Organizers said the goal was a $15 minimum wage and unionization. Similar strikes continued in New York – and spread across the world. During the so-called “Fight for $15” campaign, some workers complained about not just their low pay but franchisees’ heavy reliance on part-time work and retaliation against those who participated in demonstrations.

During New York City’s most recent mayoral campaign, about 200 fast food workers went on strike for a day in November 2012, holding demonstrations at various restaurants and one central rally outside a Times Square McDonald’s. Organizers said the goal was a $15 minimum wage and unionization. Similar strikes continued in New York – and spread across the world. During the so-called “Fight for $15” campaign, some workers complained about not just their low pay but franchisees’ heavy reliance on part-time work and retaliation against those who participated in demonstrations.

Around that time in 2012, security personnel, baggage handlers, those who clean airport cabins and other airport personnel voted to go on strike. The workers contended that they were poorly paid and struggling with management over inadequate training and equipment. Workers reversed course when the the Port Authority committed to fixing conditions by working with the contractors that employ these workers. Recurring rallies, demonstrations and petitions built up the pressure, and the Port Authority executive director issued a directive in January 2014 ordering contractors to immediately raise pay, phase in an hourly wage of $10.10 by the end of 2015 and develop plans for improved benefits. Staff engaged in short-term strikes when contractors did not implement these changes, according to Robert Hill, a 32BJ SEIU vice president.

When the strikes started, a number of mayoral candidates and other officials proclaimed themselves proponents of their cause. During his 2015 State of the City address, Mayor Bill de Blasio called for instituting a $13-an-hour minimum wage in New York City in 2016 and indexing increases to inflation, but Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office said that was a “non-starter” with state lawmakers. However, in May of 2015, Cuomo convened a state board to examine raising wages in the fast food industry. Within months, he adopted the board’s recommendation of a phased-in $15 minimum wage for fast food workers. Expanding the pay hike statewide, the governor proposed – and passed in the 2016 budget – a $15 minimum wage in New York City and its suburbs by 2021, with upstate areas reaching $12.50 per hour by the end of 2020 (when state agencies will then draft a timeline for increasing the upstate rate to $15 an hour).

Four years after the strikes started, the fast food workers may not have gotten a union, but they have raised wages across the state. Roughly half of the Port Authority airport workers have joined unions that are now engaged in contract negotiations to ensure that better benefits are actually implemented, Hill said. Initially, he said, “they were talking about it as if they were crazy. And now here we are. … Fast food workers have struck. And airport workers have struck. And retail workers have struck. As a result, it created a movement and a moment.”

The short-term strikes have become common in part because they prevent workers from being replaced, according to Doren. He said it’s difficult for companies to hire employees on such short notice: The National Labor Relations Board won’t allow companies to use replacement workers once permanent personnel or their union offer to resume work and request that staff be reinstated, without tying their return to any conditions or further action.

“The thing is, I notify you I’m on strike at 8 o’clock this morning, at 5 o’clock this afternoon, our strike ends. I’m shutting you down, really, with no time to get replacements. And so, I’m not putting the employees’ job at risk,” Doren said. “And I’m going to keep doing this until I get want I want.”

Still, these brief bursts of publicity-seeking picketing are not entirely without risk, according to 32BJ’s Hill. He said some workers had been fired during the airport organizing efforts and were only reinstated after further strikes. He also argued that giving up a day’s pay can put minimum wage workers in a financially precarious position.

With fast food and airport workers claiming victories, some union leaders sense that the more traditional strike is also increasingly viable. David Mertz, the New York City director of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, said the labor group has won concessions using the traditional strike with large companies, including at a Mott's facility in upstate New York, and at small establishments, such as car washes in New York City. After a 2011 strike sputtered, Verizon workers tried again in April 2016 and were then able to negotiate larger pay increases, smaller pension cuts and an outsourcing policy that the union preferred over what had initially been proposed.

With fast food and airport workers claiming victories, some union leaders sense that the more traditional strike is also increasingly viable. David Mertz, the New York City director of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, said the labor group has won concessions using the traditional strike with large companies, including at a Mott's facility in upstate New York, and at small establishments, such as car washes in New York City. After a 2011 strike sputtered, Verizon workers tried again in April 2016 and were then able to negotiate larger pay increases, smaller pension cuts and an outsourcing policy that the union preferred over what had initially been proposed.

“I think people looked at our strike and privately said, ‘How on earth can they possibly win?’ And when they saw that we actually had a strategy to win and that we were very successful in negotiating a good contract, it was pretty exhilarating for people – and, I hope, inspiring,” said Bob Master, assistant to the vice president of Communications Workers of America District 1, which represents some of Verizon’s workers in the region. “The fast food strikes contributed to an environment in which it was more favorable for us to go on strike.”

Despite the trumpeting of recent triumphs, demonstration strikes are not new, according to Joshua Freeman, a professor of history at CUNY’s Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies and at Queens College. Some trace the strategy back to the Justice for Janitors movement in the 1980s and ’90s, when demonstrations were used to draw attention to janitors’ working conditions. Many custodians worked for contractors, but found the landlords who dictated decisions to these contractors were often resistant to their demands until the protests began.

But Freeman said some recent organizing efforts have been innovative by invoking federal protection for striking workers who are not unionized. “Remember, for example, some of the Walmart strikes and so forth – people then went to the (National Labor Review Board) when they claimed there was retaliation,” he said. “Is it entirely new? No. But in some ways, it really is something we haven’t seen much of in a long time, and I think it does represent a kind of bolder initiative on the part of labor.”

Nevertheless, Freeman cautioned against lumping demonstration strikes in with their traditional counterparts, saying it’s comparing apples and oranges. And he said the infrequency of strikes makes it difficult to identify any trends or change in effectiveness for either short- or long-term strikes. Certainly, there have been high-profile failures, such as a strike that began in July at the Trump Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City, which the operators later announced will closeafter Labor Day. “We’ve seen some successes in both those approaches, but I think it’s still a little bit premature to say, ‘Oh, well, the climate’s changed,’ or, ‘The strike is back,’” Freeman said. “The numbers are still pretty low.”

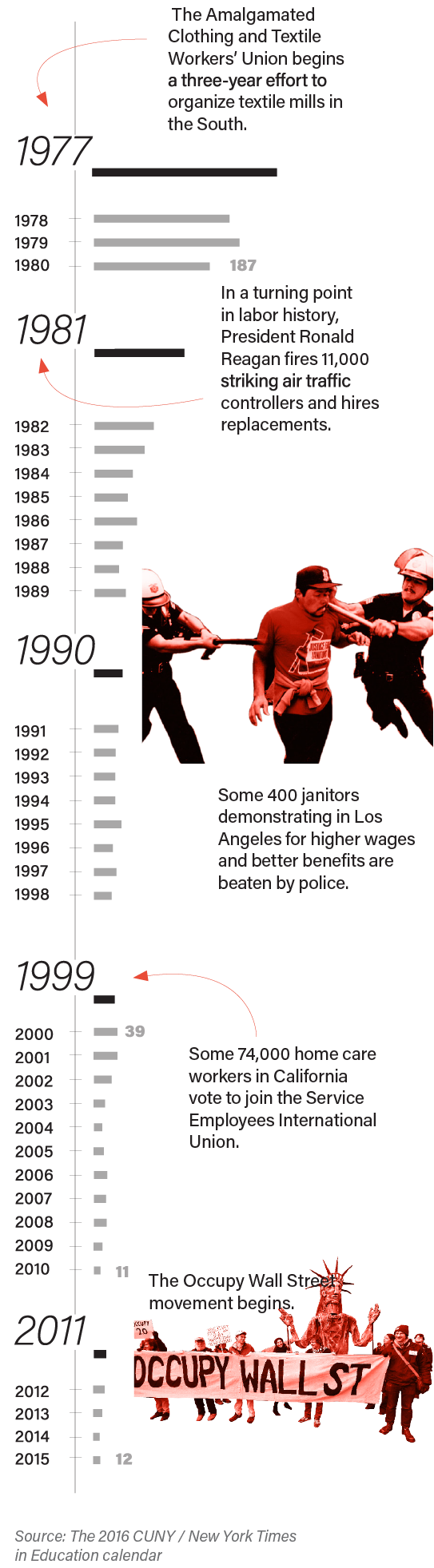

Since the federal government began tracking work stoppages in 1947, the number of annual disputes that involve at least 1,000 workers hit an all-time high of 470 in 1952. These disputes, which include strikes and employer-initiated lockouts, dropped off dramatically to 96 incidents in 1982. The decrease came shortly after then-President Ronald Reagan made good on a threat to fire more than 12,000 air traffic controllers if they did not return from a walkout within 48 hours.

Technically, strikes had long been illegal for public employee unions under federal and state laws. But historians point to Reagan’s move as one that ushered in an era in which it was more acceptable for the government and businesses to replace those out picketing, blunting the strength of the strike. By 2009, the number of work stoppages hit an all-time low of five – and the annual totals have remained in the low double digits every since. At the same time, the rate of unionization among workers has declined. In 1964, 35.5 percent of New Yorkers belonged to a union, according to NPR. Federal data shows that number fell to 24.7 percent in 2015.

.jpg) Numbers aside, many in the labor movement say the Occupy Wall Street protests showed that the public’s perception of unions had shifted – and that the followings of U.S. Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump and other populist or anti-elitist candidates provide further evidence that Americans are increasingly frustrated by the shifting economic landscape.

Numbers aside, many in the labor movement say the Occupy Wall Street protests showed that the public’s perception of unions had shifted – and that the followings of U.S. Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump and other populist or anti-elitist candidates provide further evidence that Americans are increasingly frustrated by the shifting economic landscape.

Ed Ott, the former executive director of the New York City Central Labor Council, said unions finally seem to have shaken the 1970s-era notion the general public had that unions served as organizations to defend the privileged middle class. Once again, Ott said, unions have managed to cultivate an image of partnering with low-income workers to alleviate poverty. “The fact that you see politicians standing next to unions and other organizations – workers’ organizations – willing to take an arrest with them means that there’s been a re-fusion of social justice issues and unions as being an effective tool within that struggle,” he said. In New York, for example, elected officials have been arrested at car wash workers’ strikes and airport workers’ rallies.

Even on the management side there is an acknowledgement that politicians can have an impact on labor disputes. Labor attorneys who represent management say police and legal authorities are less likely to punish strikers if they engage in misconduct when politicians stand alongside them. Even if these officials don’t regulate a given industry, elected officials retain control over tax benefits, zoning decisions and other matters, which can be a consideration for businesses, these attorneys say.

But others disagree with the notion that unions are enjoying a resurgence in popularity. Doren said he thinks only a small portion of the public – mostly Sanders followers – now look more favorably at unions. And Stephen Hans, a Queens attorney who used to represent unions but now works for company executives, said he believes there is a growing realization that unions are not generally advantageous for employees at small or mid-sized businesses. At those firms, Hans said unions are often unable to provide employees with any benefits the workers could not receive by talking directly to management.

“I think there’s also a changing attitude that is, ‘What is the union going to get for me? … Why do I have to give an extra $30 a month up to somebody?’” he said. “You’re not going to force a small to mid-size employer to reach into his pocket if he just doesn’t have it.”

And partnerships between politicians and private-sector unions have their limits. And if private unions want to cement their political status, Ott said they will have to prove that their endorsements come with the ability to turn out voters.

“If you look at the last few municipal elections, the private-sector unions – they backed this candidate, they backed that candidate – it had no impact outside of the nonprofit sector – like 1199,” he said. “If you go back into history, (Mayor Fiorello) La Guardia and others all over this city used to end the election cycle just before the November vote with a mass rally in the Garment sector to demonstrate their numbers – those were private-sector organizations that had extraordinarily well-organized operations.”