Andrew Yang isn’t serious, and he would be the first to admit it. The New York City mayoral candidate who’s leading in the polls brings a sense of fun to everything he does. When time came to deliver his petitions to get on the ballot, he jogged through a human tunnel of support before singing a – decent! – spoof of “Seasons of Love” from Rent. And when his campaign released a “Yang for New York” music video, he left the rapping to someone else, but was happy to film a scene for it. The latest Fontas/CODA poll had him leading the field with 16% of the vote, ahead of Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams at 10%.

Yang’s formula has helped him exceed expectations before. When huge crowds attracted to his presidential campaign would cheer his name at rallies, Yang would respond “Chant! My! Name!” From a career politician, this might have seemed like a horrifying act of self-entitlement. But from Yang, it was charming, and full of irony: He was a previously obscure guy with no political experience who made the Democratic primary debate stage, raised $42 million from grassroots donors, came in eighth out of his party’s presidential contenders and injected his pet issue – a $1,000 a month universal basic income – into mainstream political discussion.

Yang was in on the joke, and he did it all while having fun – skateboarding in a cafeteria, shooting whipped cream into a supporter’s mouth and even playing basketball with national political reporters, including CNN’s Chris Cillizza (who Yang easily topped, in a New Hampshire gym).

Now, Yang is taking the same approach, even though his position in the mayoral race couldn’t be more different. “In the presidential, I was the scrappy underdog,” Yang told City & State in March, before adding with a laugh, “I must say, I prefer being the front-runner, because it means I have a better chance of winning.”

With the June 22 Democratic primary fast approaching, Yang’s detractors wonder whether this unserious guy – who has shown no previous interest in city politics and government – can convince enough voters that he’s serious about being mayor.

His lead shows no signs of fading, however, and Yang shows no signs of changing his approach. He is still happy to play basketball with reporters because, as he puts it, “Who the heck wants to have these highly impersonal interactions at press conferences?”

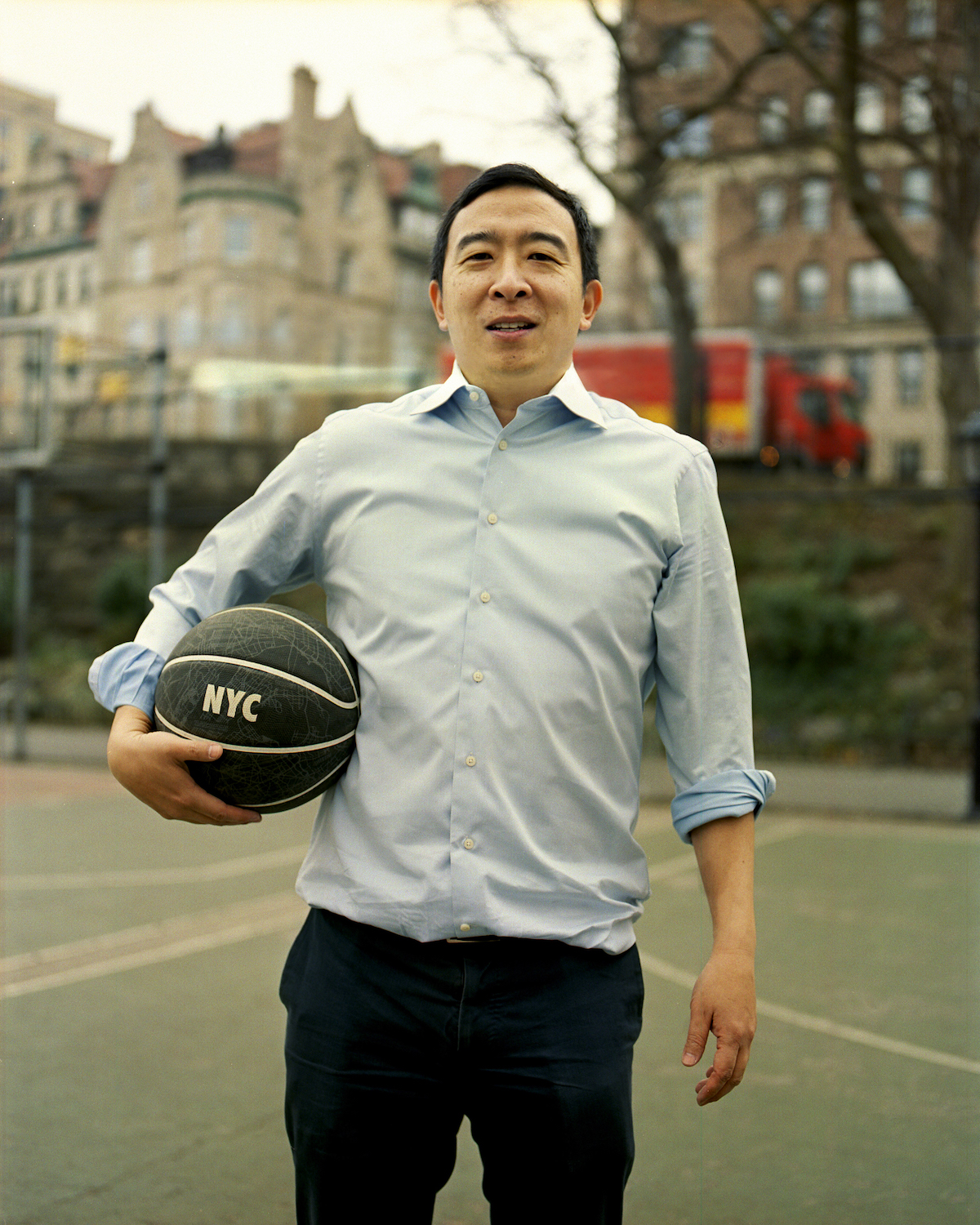

At Riverside Park in Manhattan this month, at the basketball courts at the end of West 76th Street, Yang was dressed in his usual campaign attire – slacks, a light blue button down with an open neck (never a tie, even on the presidential debate stage) and his now iconic blue and orange striped scarf and black dress shoes.

“In the presidential, I was the scrappy underdog. I must say, I prefer being the front-runner.” – New York City mayoral candidate Andrew Yang

Yang was a committed intramural basketball player in high school and in college at Brown, and he had a weekly pickup game for years, so he is still pretty good at 46, and he made short work of a much younger reporter playing “horse.” “I think there should be an outdoor basketball court at Gracie Mansion,” Yang said.

Growing up in Westchester County, Yang rooted for the Knicks, but he couldn’t forgive their 2012 failure to re-sign Jeremy Lin, the league’s first Taiwanese American player who was just coming off his breakout year, was too much for the Taiwanese American Yang. “I was so heartbroken at that, I was like, ‘I cannot root for this team.’” Luckily, the Nets had just moved to Brooklyn and their signing Lin in 2016 cemented Yang’s new loyalty.

Every candidate for mayor this year is running, in their own way, against New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. The term-limited incumbent won’t literally be on the ballot, but his seven-and-a-half year reign over the city will be. Yang’s skills on the basketball court would certainly contrast with the current mayor, who, despite being 6’5”, is a notoriously unimpressive hoops player, once nicknamed “the cactus” for the way he held his arms at a 90-degree angle. But the substantive difference is Yang’s willingness to let loose with a reporter. De Blasio isn’t known for that, and Yang is presenting an alternative. “The fact is, a lot of New Yorkers right now are looking for a light at the end of the tunnel, like a source of optimism and confidence and even joy,” Yang said. “And New York City is an incredibly exciting and joyous place in the good times. I don’t see why the mayor can’t project that kind of energy, because I think people would welcome it.”

Some who know de Blasio are quick to agree that he and Yang have differences, but they don’t necessarily see that as an asset for the neophyte, who hasn’t even voted in previous mayoral elections. De Blasio served in the City Council and as public advocate before becoming mayor.

Personality and professional resume is not the only way Yang’s approach contrasts with de Blasio’s: While de Blasio ran as the most aggressive progressive, Yang seems to be leaving the left-most lane to his competitors, emphasizing ideas for economic growth, rather than lamenting inequality. The question Yang still must answer is whether this opposite approach to the incumbent’s will get him to City Hall and leave him prepared once he’s there.

“They couldn’t be more different personality-wise, that’s for fucking sure,” said Olivia Lapeyrolerie, a political strategist with SKDK who was de Blasio’s first deputy press secretary. As Lapeyrolerie looked to a city beset by the coronavirus pandemic and its economic fallout, she wasn’t sure Yang was the antidote. “I think the challenges that we face are so serious, that the priority is who’s going to be able to actually manage the city, to steer the ship out of this crisis,” she said. “I care less who I want to have a beer with.”

This lack of direct experience is one of the most frequently raised concerns about Yang, especially among the segment of New Yorkers who are extremely engaged in politics. Yang has held a comfortable lead over all his opponents in each of the public polls released so far, but his endorsement list – despite a few high-profile backers such as Rep. Ritchie Torres from the Bronx – is remarkably sparse for a front-runner, with far fewer elected officials, political clubs or labor unions than Stringer, Adams or Wiley.

Part of the reason is that Yang is a newcomer to the race. Most of his opponents have been laying the groundwork for their mayoral campaigns for years – Adams and Stringer, more than a decade. Yang says he didn’t even think about it until he suspended his presidential campaign in February 2020, and even then not “particularly” until after Election Day in November. “That’s when I got really excited about running,” he said. “And like, I’m pumped to be here.”

“The priority is who’s going to be able to actually manage the city, to steer the ship out of this crisis. I care less who I want to have a beer with.” – Olivia Lapeyrolerie, an SKDK political strategist

Projecting enthusiasm isn’t a problem for Yang’s campaign, but demonstrating knowledge of the relevant issues is. Although Yang has been coming out with fewer eyebrow-raising policy proposals as a serious mayoral contender than he did when he was a longer than long shot presidential candidate, he has made some gaffes born of inexperience. In January, Yang proposed putting a casino on Governor’s Island to revive New York City’s post-pandemic economy. He was apparently unaware that casinos are legally prohibited on Governor’s Island under a federal deed restriction, and his casino-gambling economic revitalization strategy drew criticism from the Daily News editorial board for being a shallow gimmick. In late March, Yang assailed de Blasio for supposedly plotting to use all of the recently passed federal coronavirus relief funds in the next year, something de Blasio noted is not possible under the federal law.

Yang also has been mocked for sounding like an out-of-touch celebrity: In February, he defended his decision to flee New York City for his upstate country house during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by saying, “We live in a two-bedroom apartment in Manhattan. And so, like, can you imagine trying to have two kids in virtual school in a two-bedroom apartment, and then trying to do work yourself?” Plenty of New Yorkers don’t have to imagine that because they have been living it for the last year.

More recently, Yang – a former CNN contributor – argued that his relationship with Gov. Andrew Cuomo would be better than de Blasio’s because he is friends with the governor’s brother CNN host Chris Cuomo.

Yang told City & State that anyone who thinks he is an unprepared dilettante just needs to get to know him better. “I have to say that this concern genuinely mistakes who I am,” he said. “If you look at my background, I graduated from Columbia Law School. I was an editor of the law review. I passed the bar. I worked as an attorney. So it’s not like I’m not mindful of the way both bureaucracies and policies function.” Yang worked at a law firm for half a year in 1999, focusing on business law. He also pointed to his record running a series of businesses, and then a national nonprofit organization, saying knows how to build a team, and work in a variety of contexts. As mayor, Yang said he would surround himself “with people who are deeply experienced in city government and the operations of specific agencies.”

Yang’s allies also like to talk about the person he is. “You can go back and forth and in a perfect world you can play mix and match with people’s best qualities, but I think for me, what’s important is whether you actually care about our most vulnerable members,” said Assembly Member Ron Kim, from Queens, who has endorsed Yang’s campaign. “Andrew genuinely cares.”

While Yang’s presidential campaign wasn’t clearly identified with either the centrist or left wings of the Democratic Party, his current campaign strategy seems to include running towards the center of New York City’s Democratic field. Before entering the race, he commissioned a poll exploring whether he could win as an independent. His campaign co-manager Chris Coffey used to represent the Police Benevolent Association, the largest New York City police union, and its polarizing President Pat Lynch. The PBA and Lynch are widely despised among police reformers for their hard-line opposition to even the most modest efforts at increasing accountability and transparency for police brutality.

The candidate’s campaign platform is also on the right of the current crop of contenders. Yang generally opposes raising taxes on the wealthy and he hasn’t committed to decreasing the NYPD budget – and he has called for bolstering policing funding and staffing levels in certain situations. He also drew the ire of alternative transportation advocates by suggesting that bus-only lanes should be reopened to private cars at certain times.

Yang would be the first Asian American mayor of New York City, and he is running during an alarming surge in anti-Asian hate crimes.

Perhaps Yang is looking to build a coalition of more conservative constituencies: Yang is currently in contention for the endorsement of ultra-Orthodox Jewish religious leaders, thanks in part to his recent comments in favor of allowing yeshivas to continue neglecting to provide a secular education to their students. A 2019 New York City Department of Education report found that just two of the 28 yeshivas examined provided an adequate secular education. Yang said at a mayoral forum, “I do not think (the city) should be prescribing a curriculum unless that curriculum can be demonstrated to have improved impact on people’s career trajectories and prospects.” (Some former Hasidic Jews say their job prospects have been severely limited by their lack of necessary education.)

Yang’s casual charm has helped to make him popular among the broad Democratic electorate thus far, but progressive insiders like Allen Roskoff, who leads the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club, say that will fade when voters start taking Yang more seriously. “Yang has inconsistent positions with that of progressive New York and no history of working with groups or issues he is taking positions on,” Roskoff said. He added, “I do not know a single person, gay or straight, who’s left of center supporting him or giving him further consideration.”

When asked, Yang’s campaign doesn’t deny that he appeals to more moderate voters – but insists that his focus on a basic income is a mark of true progressivism. “Yang is the one who put the idea at the national level that we need to redistribute dollars in a broken economy to everyday people who have been hurt the most. I’m really proud that the first thing that we rolled out in this campaign was cash relief for the poorest New Yorkers,” Yang’s campaign co-manager Sasha Ahuja told City & State. “I very much so believe that Andrew must be included in that field of candidates who are part of the left.”

There are some progressives, such as Kim, who are supporting Yang. Kim argues that Yang is malleable, praising the candidate’s “passion to find solutions.”

“I don’t agree with everything, with all the policies that are coming out of his shop, but he’s always open to collaborating,” Kim said.

One constituency that may back Yang while spanning the ideological spectrum is Asian Americans, who comprise 14% of New York City’s population. A WPIX-TV/NewsNation/Emerson College poll taken in early March showed Yang with the support of 60% of Asian American likely Democratic voters, compared to 50% among white voters, 31% among Black voters and 26% of Hispanic voters.

The enthusiasm for Yang’s candidacy from an underrepresented community comes as no surprise: Yang would be the first Asian American mayor of New York City, and he is running during an alarming surge in anti-Asian hate crimes. Yang has spoken about the harm of such bigotry in personal and political terms. He noted that a 65-year-old Asian American woman who was recently attacked in his own neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen “could easily have been my mother.”

But Yang’s presidential candidacy was not greeted with universal enthusiasm among Asian Americans. Many were critical of his habit of making jokes playing on ethnic stereotypes. During one debate, he cracked “Now, I am Asian, so I know a lot of doctors,” and in another he said, “The opposite of Donald Trump is an Asian man who likes math.”

While Yang still likes to have fun on the campaign trail, he has ditched those kinds of lines this year. Some of his attempts at lightheartedness have prompted online rebukes from people who say he demonstrates a lack of New York authenticity, such as the scolds who thought he mischaracterized a deli as a bodega. To many, these attacks on Yang reek of anti-Asian bias, and the racist trope of the “perpetual foreigner,” written about by activist Nina Luo in the New York Daily News.

Jokes about Asians and math are not the only time Yang has tested the limits of political correctness: His rise to national prominence was powered in part by appearances on programs with right-wing hosts such as Ben Shapiro’s radio show and Tucker Carlson’s Fox News program. In one appearance, he said, “There are many elements of Trump voters that I completely get and empathize with,” and in another he opined that the Democratic Party, “needs to try and gravitate away from identity politics.” Female employees of his presidential campaign, the test prep company he led and the nonprofit he founded have also complained of male-dominated office “bro culture.” Some have alleged gender discrimination, which Yang and other former colleagues have denied.

In a March conversation with supporters on the audio chat room app Clubhouse, Yang sounded extremely confident, when asked about his chances. He raised a lot of money quickly, and “85% of New Yorkers have heard of me, and 65% have a favorable impression,” he said. “So right now, I am the candidate to beat, and I don’t see that dynamic changing, as long as we keep running our race.”

Walking through Times Square with Yang, the breadth of his recognition and support is readily apparent. He’s there to meet with homeless outreach workers and their clients, but he has to take a couple breaks to indulge a diverse array of fans who approach: a white teen in a lacrosse sweatshirt who said his grandma voted for Trump, but she’s voting for Yang, too; a West African immigrant who works for a tour bus company and asked if Yang has any Africans on his campaign team; an Orthodox Jewish couple with a baby who wanted a selfie with Yang; and a younger Asian American man just wanted to tell Yang he’s a fan. Yang may not have a traditional winning coalition in a New York City primary, but everyone knows him. That includes Times Square’s famous Naked Cowboy, the attention-grabbing Trump supporter who attended the Jan. 6 rally in Washington, D.C., that preceded the deadly siege of the U.S. Capitol. The cowboy approached Yang, and the candidate gamely posed with him before the cameras. Asked if he knew about the performer’s political leaning, Yang laughed in disbelief. “Really? Our Naked Cowboy? What is he doing?!” he exclaimed. “Agh. I had no idea.”

NEXT STORY: Pot legalized but the budget is late