Last summer, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a century-old New York law that had effectively banned people from carrying handguns in the state. In a 6-3 ruling in the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen, the court said New Yorkers didn’t have to show proper cause in order to obtain a concealed carry permit.

While the decision was lauded by gun rights activists as necessary and long overdue, some commentators characterized Bruen as a threat to public safety.

Michael Waldman, president and CEO of the Brennan Center for Justice, proffered an especially ominous reaction in the pages of The Washington Post: “The Supreme Court’s ruling on Thursday striking down a New York gun law isn’t just the most significant ruling on the Second Amendment in a dozen years – it may be the most significant, and most dangerous, such ruling in the nation’s history.”

In a similar tone, the editorial board of The New York Times described the decision as being “profoundly at odds with precedent and the dangers that American communities face today.”

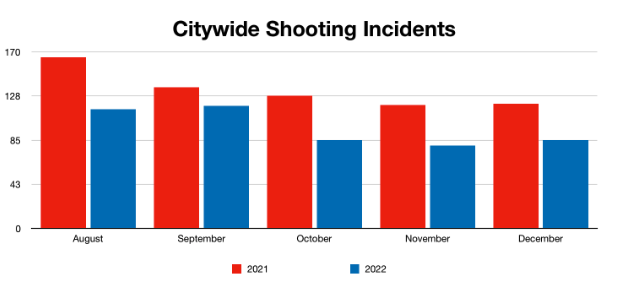

A little more than half a year later, the spate of crime implied by those foreboding prognoses has not yet occurred. And indeed, not only has New York avoided the wave of gun violence envisioned by some, but to the contrary, shootings are actually down. Compared to 2021, the months following Bruen saw fewer shootings in the last five NYPD reports of the year.

In order to understand why Bruen has not precipitated a wave of shootings, it is necessary to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of crime trends, the profuse public outrage fostered by high-profile shootings in early 2022 and the subsequent legislative efforts aimed at patching what has long been – and in many ways remains – an imperfect framework for regulating access to guns.

Bruen in context

At the center of Bruen was the constitutionality of the 1911 Sullivan Act, a state law that mandated a restrictive licensing framework for handguns. New Yorkers were required to demonstrate a particular need in order to obtain a handgun license. As adjudicated by state courts, that meant proving “a special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community.” Individuals who faced an exceptionally high risk to their safety in public – celebrities, for instance – were historically favored in this application process, resulting in concealed carry licenses being awarded to figures like former Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, Bill Cosby, Howard Stern and former President Donald Trump, much to the frustration of gun rights groups.

In this respect, New York City under Sullivan was what’s known as a “may-issue” jurisdiction – the licensing authority, in this case the New York City Police Department, may issue a license to an applicant if certain criteria are satisfied. Licensing authorities in “shall-issue” jurisdictions must allow any person to acquire a license so long as they meet basic requirements like being above a certain age and passing a criminal background check.

The plaintiffs in Bruen – the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association alongside failed concealed carry applicants Robert Nash and Brandon Koch – alleged that the Sullivan Act violated the Second Amendment by unduly establishing barriers to possessing a firearm. Accordingly, they sought to have the licensing framework modified so that applications could no longer be rejected on the basis of lacking a sufficient reason or “proper cause” for carrying a handgun in public. Nash had attempted to acquire a license on the grounds that there was recently a succession of burglaries in his neighborhood, but the NYPD deemed that these events did not sufficiently elevate Nash’s level of risk above that of the average citizen.

Prior to Bruen, two salient, landmark decisions had been handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of gun ownership in private residences: District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), and McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010).

In the case of Heller, the court held that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to possess firearms regardless of service in a state militia, as well as an individual right to use firearms (including handguns) for self-defense in the home. And in McDonald, the court affirmed that the individual right to keep and bear arms enshrined in the Second Amendment is incorporated by the 14th Amendment’s due process clause, which proscribes states from denying life, liberty, or property without due process of law.

“Heller and McDonald were essential predicates for Bruen because they established that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to own and carry weapons,” said Harvard Law School professor Mark Tushnet. “Technically, Heller held that the national government (which is the legal foundation for District of Columbia law) had to respect an individual right to possess guns, and McDonald held that state governments were bound by the same rule under the 14th Amendment.”

According to Tushnet, part of the reason the Sullivan Act was able to endure for over a century was its specificity. Unlike the regulations at the heart of Heller and McDonald, the Sullivan Act did not establish an outright prohibition of firearms, and thus, its basis in law was less susceptible to challenges from the gun rights movement.

“Until the early 2000s, the chances of a successful challenge were really low, and (the) gun rights groups who were developing a strategy decided that it made sense to proceed step by step,” he said. “So, they went after complete bans on possession by ordinary citizens in Heller and McDonald, planning to go after more detailed regulations – ‘may-issue’ laws like the Sullivan Act, and concealed carry laws – next.”

Bruen broadened the scope of Second Amendment protections from the home to the public sphere. In his authoring of the majority opinion, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas upheld the constitutionality of citizens carrying firearms outside the home.

“The constitutional right to bear arms in public for self-defense is not a second-class right subject to an entirely different body of rules than the other Bill of Rights guarantees,” he wrote. “We know of no other constitutional right that an individual may exercise only after demonstrating to government officers some special need.”

As a constitutional right, Thomas reasoned, it was inappropriate to subject concealed carry regulations to the two-part test, a model utilized by lower courts throughout the previous decade to gauge the constitutionality of gun laws. Part one of this test determines whether the law in question could reasonably be considered discordant with the Second Amendment. If that threshold is met, the second part of the test involves judicial application of “means-end scrutiny” to weigh the balance between the right to self-defense and the policy interests of the state.

Still, Thomas acknowledged the limited legitimacy of shall-issue regulations and acknowledged that the right to bear arms could be circumscribed by state and local regulators with reasonable measures like background checks.

In New York, it did not take long before that latitude was put to the test.

Legislative response

To the extent that pundits and government officials predicted that more shootings would follow Bruen, it’s reasonable to assume they did so with premonitions of a licensing paradigm that would allow more violent individuals to carry a handgun in more high-risk settings. Putting aside the issue of licensing lag times, the government’s response in the wake of Bruen has been so thorough that those predictions seem now to be obviously wrong.

While the Bruen decision created a storm of criticisms, the most vigorous reaction arguably came from Albany. On July 1, just a week after the U.S. Supreme Court’s announcement, Gov. Kathy Hochul convened an extraordinary session of the state Legislature to pass emergency gun legislation, with the aim of filling in as many of the regulatory gaps left by the Bruen decision as possible. On that same day, Hochul signed the Concealed Carry Improvement Act into law.

Among other provisions, the law broadened the criteria for a concealed carry permit by requiring four character references, firearm safety training courses, gun range testing, an in-person interview, an assessment of the applicant’s former and current social media profiles from the past three years as well as standard criminal background checks. The Concealed Carry Improvement Act also expanded the disqualification criteria for concealed carry applicants to exclude applicants with a demonstrable record of violent behavior, misdemeanor convictions for assault, weapons possession and menacing, alcohol-related misdemeanor convictions like driving under the influence, recent treatment for drug-related reasons and involuntary commitment to a department of mental health facility.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the law, however, was its listing of sensitive locations where otherwise lawfully armed individuals were prohibited from carrying: places of worship; educational institutions; courthouses; federal, state and local government buildings; polling sites; public transportation, such as subways and buses; health and medical facilities; entertainment venues; shelters, including homeless and domestic violence shelters; day care facilities; playgrounds and places where children gather; airports; bars and restaurants where alcohol is served; entertainment venues; libraries; public demonstrations and rallies; and Times Square.

Considered collectively, these regulatory additions constrain the opportunities for legally carrying handguns in New York City to an extent that is, at least nominally, reminiscent of the pre-Bruen era. While Bruen made it easier to legally own a handgun in New York, a flurry of countervailing forces has made it harder.

Last spring represented an inflection point in America’s gun debate, and examining the Bruen decision’s impact on gun violence without simultaneously recognizing the passage of historic gun control legislation betrays a total misunderstanding of the issue’s complexity.

Even before the Bruen decision came out, concerted efforts were being made at both the state and federal level to address gun violence – an issue that held the national conscience after the May 14 racist mass shooting at a Buffalo grocery store. On May 24, as the nation continued to grieve, an even greater loss of life occurred in Uvalde, Texas, where 19 students and two teachers were killed at Robb Elementary School.

Both events brought about a groundswell of support for tighter gun restrictions. According to data from a June 2022 NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist poll, the weeks following those two shootings saw the greatest public support for increasing gun control in a decade.

It was, therefore, unsurprising that June 2022 also saw the passage of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, the first major piece of gun legislation to be passed by Congress since the 1994 assault weapons ban. This landmark federal law, a rare product of bipartisan cooperation designed to increase funding for mental health services, enhanced background checks for gun buyers under the age of 21, broadened the requirement for sellers to obtain a federal sales license and prevented individuals with misdemeanor domestic violence convictions from owning firearms.

Bruen may have removed barriers to accessing handguns for certain people, but overall, last summer was far from a shift toward looser access to guns – in both New York and across the country.

Legal challenges

Predictably, Hochul’s Concealed Carry Improvement Act was challenged in lower courts immediately after being signed into law – the principal grievance being that the legislation precluded the right to publicly carry affirmed in Bruen by imposing restrictive limitations.

On July 11, Gun Owners of America launched a lawsuit, Antonyuk v. Bruen, in an attempt to overturn a provision of the law that required aspiring concealed carry licensees to submit a list of all their social media channels as part of the standard vetting process, in addition to the historic provision requiring applicants to provide four personal references. Moreover, the lawsuit targeted the law’s new “good moral character” requirement, a provision that gun rights activists characterized as a thinly veiled and equally unconstitutional replacement for the “proper cause” dimension of the Sullivan Act. On Aug. 31, U.S. District Court Judge Glenn Suddaby dismissed the case on the grounds that the group lacked standing.

On Sept. 20, Gun Owners of America’s Ivan Antonyuk launched a second suit, Antonyuk v. Hochul, again aiming to reverse the law, but this time naming a more varied list of defendants, including Hochul, multiple district attorneys and local licensing bodies. On Oct. 6, Suddaby granted the plaintiffs a temporary restraining order, ceasing the enforcement of various key provisions of the law, including the prohibition of handguns in areas like Times Square and the subways. This temporary restraining order lasted only a week, however, before it was reversed by the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

On Jan. 11, the Supreme Court dismissed an emergency request, Antonyuk v. Nigrelli, to remove the 2nd U.S. Circuit’s stay, thereby allowing authorities in the state to continue enforcing the provisions of the law that Suddaby deemed unconstitutional. But as Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito (joined by Thomas) conveyed, the decision not to grant Antonyuk’s request was a result of “respect for the Second Circuit’s procedures in managing its own docket rather than expressing any view on the merits of the case.” A Supreme Court intervention remains possible.

Bruen’s impact

With the Concealed Carry Improvement Act still intact, Bruen’s true impact remains unclear. Has the decision made New Yorkers more vulnerable to gun violence? Will it make them more vulnerable in the future? Like all types of crime, the prevalence of shootings has a long list of legal and sociological correlates. And like all types of crime, direct attribution to singular policies or laws is impossible.

Unemployment rates, policing tactics, reporting methodologies, the weather … and yes, gun laws are just some of the countless variables that influence the volume of shootings.

Ostensibly, the reason Bruen didn’t lead to a significant increase in gun crime was because it’s still incredibly difficult for most New Yorkers to get a gun. The legislative reactions in the wake of Bruen were swift, forceful and comprehensive – and accordingly, New York doesn’t look like the ubiquitous holsters seen in the Wild West.

It may be misguided to ascribe a causal relationship between shifts in gun violence and a specific piece of legislation or court case, but even if it weren’t, the downward trend suggests Bruen’s impact on gun violence was much more complicated than its vocal detractors first assumed.

Samuel Forster is a former associate at the University of Toronto Centre for Ethics and current freelance writer focusing on politics and current affairs.

NEXT STORY: Opinion: We need to end the foster system to prison pipeline