The very creation of Nassau County was in some sense an early reaction to the Big Apple. “During the consolidation of the five counties in and around Manhattan into the new municipality that became the City of New York, local residents on Long Island lobbied the state legislature to establish a new county independent from the city,” writes Nassau native and GOP political guru Michael Kaplan in an unpublished manuscript detailing the local party’s prehistory. “Albany lawmakers acceded to their demands and on January 1, 1899, Nassau County was created.”

For the next hundred years, the county would be reliably Republican, particularly in local elections, instinctively positioning itself against the behemoth next door. The mantra changed over the generations – sometimes it was “protecting the suburban character of Nassau County,” as GOP chair Joseph Margiotta said in the 1980s, years after he fought the construction of affordable high-rise apartments. Sometimes the “sixth borough” was invoked, as in, residents wouldn’t want Nassau to become that. Or, in the early 20th Century, the prayer to “keep the Tammany tiger out of Nassau,” referring to the tightly controlled party boss system that had thrived in the city for decades.

The irony was that the Nassau GOP was pioneering something of a Tammany system of its own out in the suburbs, where patronage was the way of the world and locals knew to talk to partisan leaders for even seemingly civic problems. The system’s initial architect, J. Russell Sprague, was so tightly controlling that he is known for his somewhat-legendary instruction, “Always know how a meeting is coming out before you call it.” Sprague’s great coup was assimilating the newcomers who flocked to Long Island as the suburban age of America dawned. Levittown, and its government-subsidized cookie-cutter houses, was the center of that story. The newcomers were often white ethnic Democrats, notes Marjorie Freeman Harrison in a 2005 thesis on Nassau politics. The Republicans were relentless: “GOP representatives were tipped off by letter carriers when a new family arrived, and the party, in the person of a friendly neighbor, arrived at the doorstep to assist with the details like making sure garbage was picked up and broken sidewalks fixed.” This partisan centrality to daily life had its legal pitfalls when political leaders overstepped – say, with the kickback scheme that ensnared party chair Margiotta in the early 1980s. But even a seriously shocking scandal or six wasn’t enough to shake up the strong GOP machine, which at that time was still the place to go whether you wanted to become a top county official or a summer lifeguard. Ronald Reagan himself once acknowledged how fertile Nassau’s territory was for the GOP, claiming that when a Republican goes to heaven, it looks a lot like Nassau County.

The party was also rigorous about where it got its candidates (from within) and how it sculpted them (almost to a mold). For some time, there used to be what was called “charm school” for candidates, current GOP chair Joe Cairo told me. Cairo is a happy warrior and sports fan who went to the only out-of-state university New York politicians of a certain type are allowed to attend (Notre Dame). Cairo himself attended charm school in ’75, after he was appointed to fill a death-related vacancy on the Hempstead town council. To get ready to face the voters, he first had to go see an etiquette expert in Manhattan, every Friday afternoon for around ten weeks. There were moments of culture clash in the expert’s doorman building overlooking Central Park. Cairo didn’t like her advice about overpronouncing words: “Thursday,” say, with a nearly r-less flourish. You’d get laughed outta town back home for talking like that. But there were useful lessons about decorum, and how to be taken seriously. To this day he still wears over-the-calf socks on the off chance that he crosses his legs at a meeting and the suit pants ride up. And he learned how to address a crowd, how to fight through nervousness – pick out one person, just one person in the room. And speak to them.

The political situation in Nassau County is different than it used to be in the charm school days. Former U.S. Sen. Al D’Amato, who jumped from town office in Nassau to the Capitol in 1981 and stayed there for eighteen years, is now a pot lobbyist and name on a federal courthouse, as well as the last Republican to win a U.S. Senate seat in New York. Locally, Democrats have made inroads, so much so that they now outnumber Republicans by party registration, if not voting inclination. There is no more charm school, and the party’s candidates are less afraid to break the old mold. It used to be said that there was such a thing as “Republican hair” – straight, coiffed, and combed back, probably white, certainly Caucasian. There had never been – or at least Cairo cannot remember – an openly gay member of Congress from the party in Nassau.

Which is where George Santos fits in, at a moment of flux for the party. The machine does a kind of vetting through lifelong knowledge of candidates, being warned if so-and-so drinks too much, has a gambling issue, or a girlfriend or two on the side. But Santos was not a party person, not among the Nassau farm team, Cairo wants to make that very clear. He was not a former baseball coach or town trustee or village mayor before he made the leap to Congress. He was not a committeeman who spent years walking the petitions necessary to get candidates onto the ballot. He was a Queens guy, not even recommended very highly by the Queens party chair at the time, frankly, but in 2020, who else was going to run for what was sure to be a losing race against a longtime Democratic incumbent?

There are a few things that stuck out to Cairo about his encounters with this newcomer. Of course there was the time Santos came into Cairo’s office at GOP headquarters and launched into his fantastical volleyball story. That he’d been sort of a star at Baruch (where by the way he’d graduated summa), and had actually been a “champion.” That was a word that Cairo did not take lightly. He had all kinds of memorabilia in his office – a picture of him as a high school football official, and a piece signed by the legendary Fighting Irish coach Lou Holtz that sat right in Santos’s eyeline, and it said “Play like a champion today.” Champion. It does make you think.

But mostly, Santos seemed like someone the party could run and basically ignore. The newcomer intimated as much, portraying himself as a wealthy Wall Street type with the ability to tap his network and easily fund his campaign without much help from the party coffers. He once told Cairo offhandedly that he’d been looking at expensive houses on Long Island and had even made an offer in the $2.5 to $3 million range. At one point he confided that he was “handling finances” for Linda McMahon, the former Trump official and wrestling mogul. He said he was going to call her up and get a big check from her (his filings do not show such largesse).

Cairo is no dummy. He must not have hated the fact that wherever the money came from, Santos-affiliated accounts gave over $180,000 to Nassau Republican Party committees alone. (The committees refunded large portions of that money after Santos imploded.) It’s a stretch for him and the Nassau Republicans to mostly blame the Queens GOP for Santos, given that Nassau made up the majority of the 3rd Congressional District during both of the fabulist’s runs. In 2022, Nassau had nearly 80% of the district’s registered voters. Queens certainly wasn’t strong enough to boss around the storied Nassau machine here. Santos would have been an also-ran if Cairo and his party decided to block him.

But there were signs that the kid understood the program, or what the world was like in Nassau, even if he was an outsider with a strange resume. Coming into the 2020 campaign, Cairo said, Santos shared that he had been using his mother’s name because he had been close to her and his father wasn’t a big part of his life. But he planned to use his father’s name – Santos – now because “politically that might be more advantageous than Devolder.” Cairo’s assumption was that the up-and-comer felt it was more ethnic. If you squinted, it was almost Italian.

In this way, a party that had once forced candidates through the grinder of charm school now shrugged and said “go ahead” to someone unvetted.

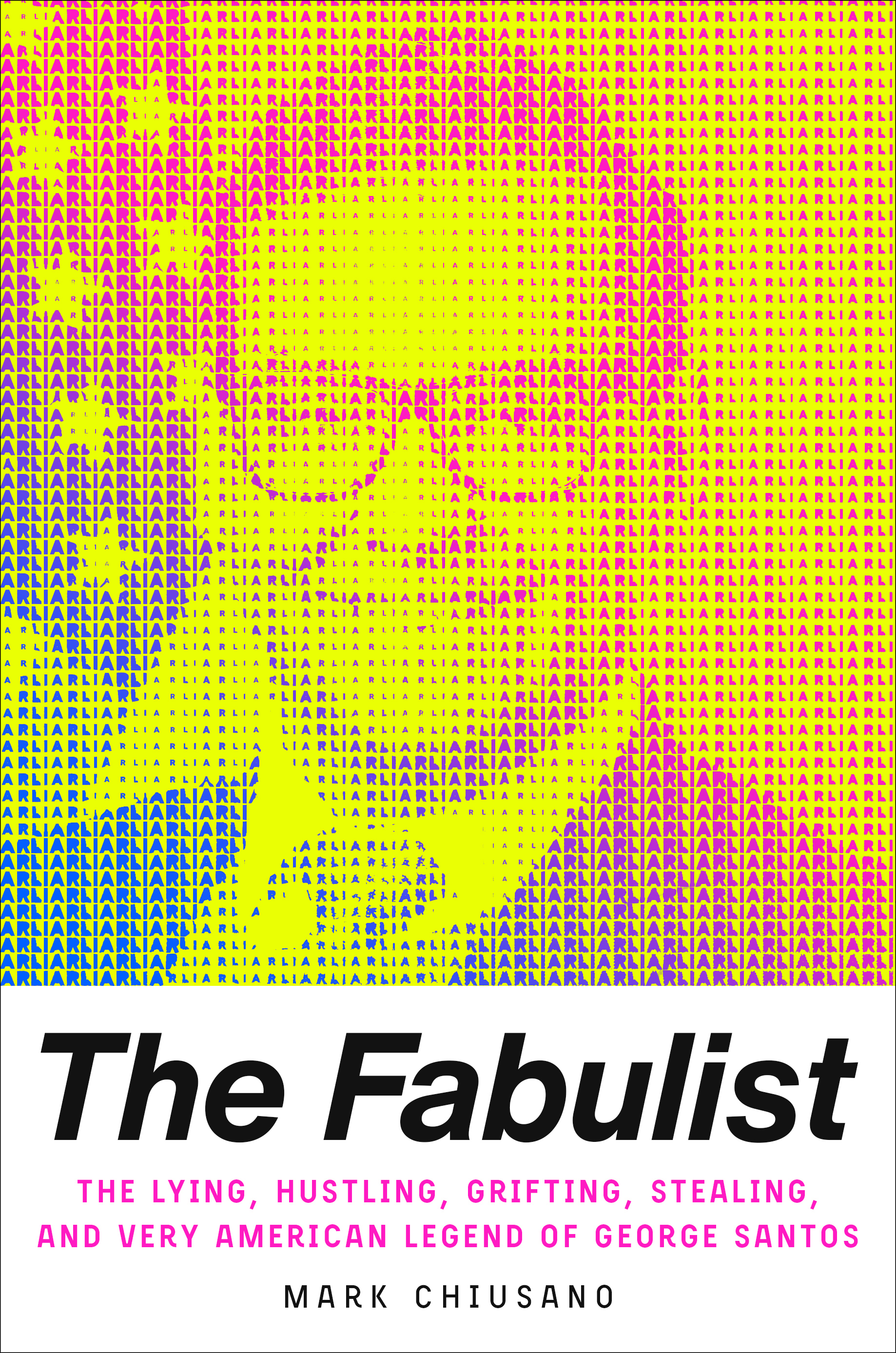

Excerpted from The Fabulist: The Lying, Hustling, Grifting, Stealing, and Very American Legend of George Santos, by Mark Chiusano (published Nov. 28 by One Signal/Atria, a division of Simon & Schuster).

NEXT STORY: This week’s biggest Winners & Losers