Criminal Justice

What does criminal justice reform look like to Kathy Hochul?

The governor has reservations about “defund the police” that her No. 2, Brian Benjamin, doesn’t seem to share.

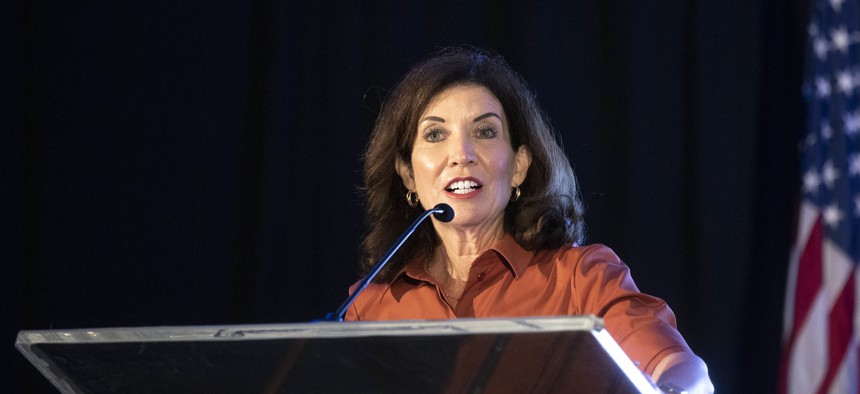

Government transparency and accountability was among Hochul’s early priorities in the wake of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s opaque approach to governance. Mike Groll/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

“We do not support ‘defund the police.’ No one in my administration does.”

That was Gov. Kathy Hochul’s response to a question last week about a tweet from her lieutenant governor in January. “I support the movement to defund the police because I believe that there are parts of the NYPD budget that are not essential for public safety,” read a campaign statement from Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin when he was still running for New York City comptroller. There is certainly daylight between the new pair when it comes to the issue of criminal justice reform, on which Benjamin was a leader in the state Senate.

Hochul’s stance on the movement to defund the police, which she referred to as a “catch phrase with very negative connotations,” is perhaps unsurprising. Moderate lawmakers like Hochul have generally shied away from the language or, as she did, outright condemned it. Early action like signing the Less is More Act to reduce the number of people reincarcerated for parole violations and selecting Benjamin as her lieutenant governor are good first steps on the issue in activists’ eyes, but many are still waiting to have conversations to assess what sort of partner she will be moving forward.

Government transparency and accountability was among Hochul’s early priorities in the wake of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s opaque approach to governance. Joo-Hyun Kang, executive director of Communities United for Police Reform, said the sentiment was welcomed but that it must extend to all parts of the public sector, including police and their unions. “If we take her at her word for that, then that should mean that she should take hard stances and be bold about the need to curb the impunity of police departments across the state,” Kang told City & State.

Communities United for Police Reform is working on a new package of legislation for the state level for next year, according to Kang, after the successful push to repeal the police discipline privacy law and other priorities in 2020. How Hochul responds to those priorities will serve as a litmus test for coalition members. “We hope that her choice of Brian Benjamin is an indicator, but you never know… until the actual moments where she has to make things happen,” Kang said.

Certainly, Hochul’s selection of Benjamin for lieutenant governor was welcomed by the criminal justice reform community. At the announcement of the selection in August, Hochul touted Benjamin’s leadership on issues of criminal justice, tenant protections and affordable housing, which she called “three huge priorities of mine as well.” When Benjamin was sworn in in September, the governor mentioned that criminal justice was something at her “core,” and that ensuring police accountability was something she would be working on “collaboratively” with her new No. 2. But when Benjamin described the three specific tasks that Hochul had asked him to lead on early on, criminal justice reform was not among them. (Those areas of leadership include heading a task force on the New York City Housing Authority, addressing vaccine hesitancy and rent relief disbursements.)

“The reality is there is work to do,” said Katie Schaffer, director of organizing and advocacy at the Center for Community Alternatives when asked about Hochul’s recent statements about defunding the police. Since taking office, Hochul also seemed to indicate that she would be open to revisiting bail reform in an interview with The New York Times. Schaffer said that in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and growing recognition among Democrats that police department budgets are perhaps unnecessarily large, “it’s disappointing to see (Hochul) capitulate, at least in rhetoric, to the sort of reactionary forces there.”

For his part, Benjamin said after Hochul’s comments that his own stance on the issues hasn’t changed and that he and the governor see eye to eye. “My stance has always been that (the) police budget needs to be reflective of the needs for public safety, and to the extent that that is happening, then I am perfectly okay,” Benjamin told Spectrum News last week, though without mentioning the prospect of reducing police department budgets. Hochul herself last week said that she believes “we have to continue to fund the police in this state to make sure that they can protect particularly Black and brown communities.”

Still, criminal justice and police reform go beyond the slogan of defunding the police. Hochul, while denouncing the movement, indicated that she would be a partner on continued reforms moving forward, albeit through vague statements. “The status quo is not acceptable,” Hochul said last week. “There are reforms that can and should and will be in terms of better communication. And anytime someone – a member of law enforcement – crosses the line… there will be very severe consequences.” Like many Democrats in the state, Hochul has received monetary support from police unions – generally the most significant roadblocks to reforms – and given no indication that she will reject their donations as some New York City progressives have pledged.

Schaffer is giving Hochul time to assess the issues and listen to feedback from communities impacted by policing and incarceration before passing any sort of judgment on the new governor. Schaffer said that her organization is in the early stages of reaching out to the administration to begin those discussions. She pointed to Hochul’s signing of the Less is More Act as an indicator that the governor is at least willing to come to the table and listen to those impacted by the criminal justice system. “There are substantial and important issues that are currently before the Legislature that Gov. Hochul has the opportunity to support ... in the coming legislative session,” Schaffer said.

Chief among them are the Clean Slate Act, which would erase the public criminal record of of most people convicted of a crime after serving their time, the Elder Parole bill, which would make certain incarcerated people over the age of 55 eligible for parole, and Fair and Timely Parole, which would make it easier to get released on parole. All three failed to pass the Legislature this year. Hochul has not offered public comment about these pieces of legislation, but a spokesperson said the governor would review them if they pass. Assembly Member Catalina Cruz, sponsor of the Clean Slate Act, told City & State that she had not yet spoken to Hochul about the bill, but said it would be a priority next year.

NEXT STORY: MTA to start enforcing $50 mask fines