New York City

Two years after George Floyd’s murder, where have all the police reforms gone?

The NYPD budget has been restored, anti-crime units reinstated, disciplinary records have been withheld and few officers have been punished for aggression toward protesters.

A Black Lives Matter protest in Times Square in July 2020. Pablo Monsalve/VIEWpress via Getty Images

The 2020 racial justice demonstrations in New York City became a stage for the brutal police tactics that drove protesters to the streets following the murder of George Floyd on May 25 of that year. Dozens of videos of New York City Police Department officers shoving, beating and pepper-spraying protesters emerged, sparking even more outcry. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio was widely criticized for his response – or lack thereof – to NYPD aggression against protesters, leading members of his own staff to publicly denounce his approach to criminal justice and policing.

What began as an emotional response to police brutality evolved into a movement to “defund the police.” Beyond calls for cuts to the massive NYPD budget, demands from protesters in 2020 were far-reaching, including everything from emptying Rikers to enhancing officer accountability.

On a state level, the Legislature responded to protesters’ demands by passing a package of reforms aimed at lifting the “Blue Wall of Silence,” a term that refers to police departments’ attempts to hide officer misconduct, by limiting the use of chokeholds by police and requiring officers to record demographics when making low-level arrests.

The City Council also passed a package of reforms that summer on officer accountability and to tamp down excessive force, along with cataloging surveillance technology.

But as the Black Lives Matter protests swept the city and the country, so did a pandemic-induced counterforce to the progressive policereform movement. The unraveling of societal norms contributed to a national increase in shootings and homicides. Domestic violence incidents spiked as victims were stuck at home with their abusers. The uncertainty drove record increases in gun sales across the U.S. School closures, along with household disruptions, were widely believed to have contributed to an increase in killings and violence among youth. Distrust in police reached an all-time high.

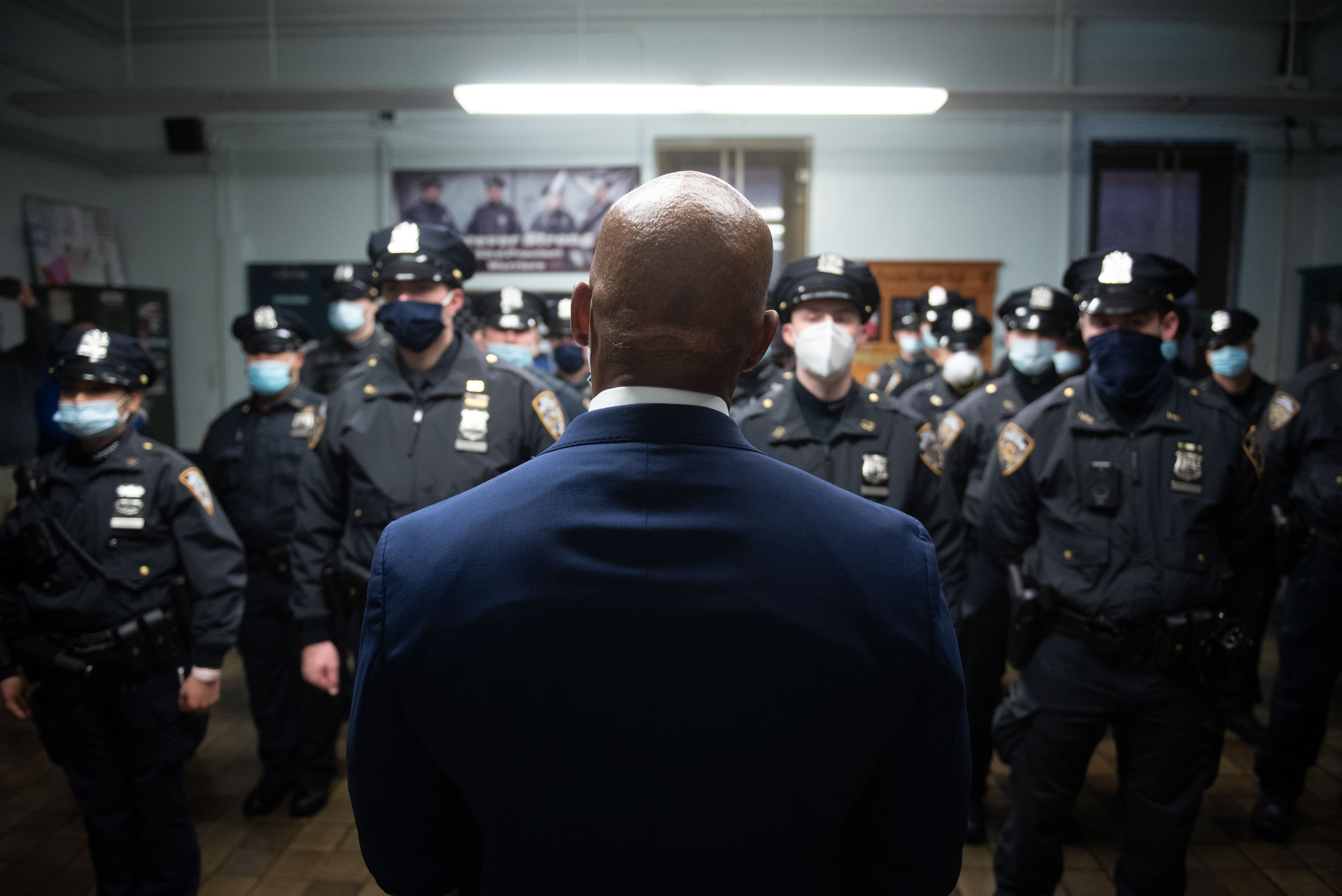

In the two years since Floyd’s murder by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota – and the popular movement sparked by his death – these factors have contributed to a marked shift away from policies and rhetoric meant to radically change the role of policing in New York. New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a former police officer, has reinstated the controversial NYPD anti-crime unit and proposed an NYPD operating budget that maintains the increases under de Blasio, exceeding the budget put in place before the protests.

Adams participated in the 2020 protests as Brooklyn borough president. During the mayoral primary, he touted his work as a reformer of the NYPD who called out racism from the inside. He helped paint “Black Lives Matter” in front of Trump Tower in July of that year.

But the city’s second Black mayor now finds himself on the opposite side of the police reform debate. While he once stood in solidarity with Black Lives Matter demonstrators, local leaders of the protest movement have reacted to many of his new policing policies with vitriol. Brooklyn Movement Center Executive Director Anthonine Pierre recently penned an op-ed in the Daily News in which she accused Adams of “caving to the demands of the police instead of meeting the needs of Black communities.”

Adams, in turn, has used the movement’s own rhetoric to contest the criticism and what he views as the movement’s lack of action against gun violence. “If Black lives matter, then the thousands of people I saw on the street when Floyd was murdered should be on the streets right now stating that the lives of these Black children that are dying every night matter,” Adams said in April on NY1, speaking about the Brooklyn subway shooting in April. “We can’t be hypocrites.”

In this new political climate, Adams has also promised policies to target underlying causes of crime and community-police relations – such as new investments in the city’s mental health crisis teams and youth programs – advocates said they’re overshadowed by a return to what they view as problematic policing tactics.

“All Adams has done is create more of a narrative of ‘The way we combat violence is by more policing,’” Jessica Sanclemente-Gomez, board chair of the police reform organization the Justice Committee, told City & State. “And it’s really disheartening at this point to be going back to broken windows policing the way (former Mayor Rudy) Giuliani did. That clearly showed no real dent in creating a better system and better flow of accountability.”

Adams, when asked by City & State where he thinks the city stands in implementing the reforms he and others called for in the wake of the 2020 protests, said he remains committed not only to holding bad cops accountable, but also to supporting police.

“You had (calls to) ‘defund the police.’ I didn’t call for those. … I support police accountability. I also support police support. We need to be there for law enforcement officers,” he said during a Q&A with reporters on May 18. “The small number that are not suitable to be police officers, they need to expeditiously be removed from our department because they hurt our police department.”

“There are some specific reforms I called for … there may be reforms that I don’t think are reforms. I think they could hurt public safety. And I’m never going to do anything that’s going to hurt public safety.”

Reforms enacted at the state and city levels have resulted in some changes to holding police accountable for incidents of violence and racial bias, but they have also faced fierce legal challenges and stonewalling from police departments and their unions.

Here’s where some of the most prominent police reforms that came out of the 2020 protests stand today.

Defund the police

What was promised: Amid calls from protesters, de Blasio agreed to cut the NYPD budget by $1 billion. The City Council approved the budget in August 2020, and council leaders and activists accused the mayor of using some budget trickery to create a perception that funding had been cut more significantly than it was.

Where we are now: De Blasio ultimately fell short of the demands, and the police budget has since been restored to an amount that’s even higher than it was before the 2020 protests.

The fiscal year 2021 budget, which was approved in July 2020 amid the summer protests, included $4.9 billion in city-funded NYPD operating expenses, what was projected to be a $345 million reduction, according to the Citizens Budget Commission. A large portion of the proposed reduction came from “unrealistic cuts to overtime,” the CBC reported. “These savings are unrealistic; they were not accompanied by a plan or operational strategy, and prior efforts to reduce overtime at the uniformed agencies have been more successful in slowing growth rather than decreasing expenses.”

In reality, the city spent $317 million less on the NYPD’s city-funded operating budget in fiscal year 2021 compared to fiscal year 2020, according to the CBC. Overtime expenses exceeded the projected cuts by $216 million.

The fiscal year 2022 NYPD budget raised the NYPD’s operating expenses by $465 million to a level even higher than its preprotest budget.

In addition to promises to cut overtime spending, de Blasio also pledged to shift funding for school safety agents and crossing guards to the city Department of Education, but that never happened. Adams’ first proposed budget also keeps school safety agents under the NYPD.

Adams’ NYPD spending plan, pending approval from the City Council, raised city-funded operating expenses by $539 million, according to the CBC. “This increase is largely due to the city employing a one-time, $500 million use of American Rescue Plan funds” in the previous fiscal year, said CBC Deputy Research Director Ana Champeny. However, the full picture of projected NYPD spending in fiscal year 2023 has yet to be determined due to an expected influx of federal funds. As of now, city-funded operating expenses are budgeted at $5.3 billion.

Rather than calling for blanket budget cuts to the NYPD, progressive City Council members and community activists have become more targeted in their rhetoric, instead focusing on reinvestments in programs and services to curb the underlying causes of crime and negative interactions with cops.

In a statement responding to Adams’ Blueprint to End Gun Violence, the progressive advocacy group Communities United for Police Reform had a mixed reaction.

“Pieces of Mayor Adams’ plan support non-police safety solutions that we have been demanding for years, like expanding the Summer Youth Employment Program and providing resources for programs and organizations in communities working to interrupt violence,” the organization wrote in a statement. “But these initiatives are made secondary to an approach that increases the power and reach of the NYPD, expands the notoriously violent plainclothes unit, and doubles down on dangerous police surveillance technologies.”

Adams’ gun violence plan included plans to offer “a record number” of 100,000 summer job opportunities for young people ages 14-24. Advocates, however, have called for at least an additional 50,000 spots to meet the high demand for the program.

Reformists said that while they’re not marching the streets en masse, the 2020 protests shone a spotlight on their movement and drew new recruits and resources that they have used to further their goals. They’re now working to strike a balance between the “defund” rhetoric and more practical solutions.

“You can’t just say, ‘defund the police’ and that's it,” Sanclemente-Gomez said. “It’s defund the police to redirect that funding to potentially pay teachers more or to provide more affordable housing. Communities want a lot more … and for us to not really be able to dive deep into what that strategy could look like, is a disservice to us as organizers.”

50-a repeal

What was promised: Among the bills state lawmakers passed targeting police reform in the wake of Floyd’s death was the repeal of the state’s Section 50-a law. Sponsored by Assembly Member Daniel O’Donnell and state Sen. Jamaal Bailey, the bill largely rescinded the 1976 law that shielded officer disciplinary records from the public. Under the 2020 legislation, disciplinary documents are subject to release via Freedom of Information Law requests.

Where we are now: The 2020 law has faced legal roadblocks from police unions that have sued to prohibit the release of records, some successfully. Police departments have also found ways to circumvent 50-a’s repeal by using narrow interpretations of the law to deny records requests. The New York Civil Liberties Unionsued the NYPD in September, claiming its complaint database published in March 2021 following 50-a’s repeal only included details of investigations that were “substantiated.”

Sanclemente-Gomez said the 50-a legislation was “definitely progress” and sparked a new conversation surrounding police accountability, but “it is not the silver bullet by any means. We just chipped away at the problem.”

Legislation introduced earlier this year by Assembly Member Jessica González-Rojas and Baileysought to formally eliminate the availability of the “unsubstantiated” excuse. The bill would amend the 2020 law to explicitly state that records can not be denied “because such records concern complaints, allegations or charges that have not yet been determined, did not result in disciplinary action or resulted in a disposition or finding other than substantiated or guilty,” according to the bill text.

While the legislation is still in committee, another bill that changed some of the provisions under the repeal of 50-a was recently passed and signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul on March 18. The law removed the requirement that a judicial hearing be held to determine if disciplinary documents related to an ongoing investigation – an exception frequently cited by police departments – can be withheld. Instead, under the newly passed amendments, government agencies must simply obtain a certificate from the investigating agency “that the FOIL-requested records may be withheld because they would impede an ongoing investigation,” according to an explanation of the bill, which was sponsored by Democrats state Sen. James Skoufis and Assembly Member Steve Englebright.

There was some disagreement about whether the new changes would hinder or help public access to records. The government watchdog group Reinvent Albany said the newly enacted provisions improve transparency by requiring police departments to explain why releasing records would impede an ongoing investigation. But some legal experts have said it gives police departments more leeway in making those determinations by eliminating judicial intervention. “We are back to a situation where the police simply have to give no justification, just blanket denials for access to information. They can simply cite the existence of an ongoing investigation,” lawyer James Henry told the New York Post.

Disbanding the NYPD anti-crime unit

What was promised: Amid the protests, de Blasio promised to do away with the city’s anti-crime unit that was notorious for its controversial use of stop and frisk. Former NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who put Eric Garner in a lethal chokehold while arresting him on Staten Island in 2014, was a member of the anti-crime unit. Made up of about 600 undercover police officers, the unit was formally disbanded in June 2020 under former NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea. “I would consider this in the realm of closing on one of the last chapters on stop, question and frisk,” Shea said at the time.

Where we are now: In one of his first major policing announcements, Adams said the city would bring back the anti-crime units, sparking criticism from progressive City Council members and criminal justice activists.

“The anti-crime unit has just been rebranded in some other capacity, especially under Mayor Adams,” Sanclemente-Gomez said. “We’re just going back to square one.”

The units, now called Neighborhood Safety Teams, were deployed on March 14. The approximately 200 officers are divided into groups of five officers and one sergeant, stationed in 30 precincts and four housing police service areas where 80% of the city’s gun violence occurs, officials have said. While the officers historically wore street clothes, they now wear a less conspicuous version of the NYPD’s uniform. Adams said the officers selected for the teams would undergo enhanced training and a strict vetting process.

“These anti-crime teams are not the anti-crime teams of old. They look different. They’re vetted different. There’s significant oversight," NYPD Commissioner Keechant Sewell said during a March City Council hearing.

A spokesperson for the mayor said Adams “will not allow abusive practices to take place” within the NYPD. “To show his commitment to transparency and accountable policing, Mayor Adams is making sure the NYPD’s new anti-gun unit will not make the mistakes of the past. Like all uniformed officers of the NYPD, the Neighborhood Safety Teams all wear body-worn cameras. Additionally, all members of the anti-gun unit wear modified uniforms that clearly identify them as NYPD,” spokesperson Fabien Levy said in a statement.

The units were supposed to be responsible for finding illegal guns, but department data showed most of their arrests have been for low-level crimes. As of April 5, the most frequent arrest made by the units was for criminal possession of a forged instrument, such as a fake ID. The teams had made 27 such arrests of 135 total, according to the NYPD. As of May 10, the unit had made 397 total arrests and removed 69 guns, according to the department.

Meanwhile, a federal monitor reported earlier this month that the NYPD continues to underreport stops but “has made significant strides” regarding stop and frisk, including increases in justifiable stops and the use of body-worn cameras. However, the monitor found that 29% of stops made by the NYPD last year were not properly documented, something the department said was, in part, an effect of the pandemic. “This report describes many accomplishments primarily relying on data from 2019-2020,” the NYPD said in a statement. “In the time period since the report, compliance has steadily and consistently increased.”

Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act

What was promised: First introduced in 2017, City Council legislation requiring the NYPD to publicly report technology it uses and plans to acquire in order to surveil the public, such as drones and license plate readers, gained momentum during the 2020 protests and passed in June of that year. In 2019, national backlash to the use of facial recognition software by police and bans on the technology in other cities, such as Oakland and San Francisco, also brought renewed attention to the legislation. The NYPD has used facial recognition on children as young as 11 years old to compare crime scene photos to mug shots, The New York Times reported. Department leaders staunchly opposed the legislation, stating that it would “help criminals and terrorists” and “endanger police officers,” Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence and Counterterrorism John Miller said in an interview with AM 970’s John Catsimatidis in 2017.

Where we are now: The NYPD in January 2021 released a list of the surveillance technology it deploys, including geolocation tracking devices and mobile X-ray technology, along with an “impact and use policy” for each device. Advocates said the data dump did not go far enoughand did not disclosewho is shared on the information collected from the technology or how the NYPD prevents racial biases historically associated with the technologies. “In general, the disclosures obscure the breadth, depth, and complexity of the NYPD’s surveillance, and in some instances even include misrepresentations and inaccurate statements,” the NYCLU wrote in response to the release of the information.

Advocates continued to report racial bias associated with facial recognition software – technology that faced widespread criticism for its use during the 2020 protests. The technology was used to track down Black Lives Matter activist Derrick Ingram, a co-founder of the group Warriors in the Garden, who was accused of yelling in an officer’s ear through a megaphone during the protests. Days later, in August 2020, dozens of NYPD officers swarmed his Hell’s Kitchen apartment building in an hourslong standoff. Amnesty International, along with the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, sued the NYPD to demand it release records showing how it used facial recognition software during the protests.

In February, Amnesty International reported more troubling revelations about facial recognition software. The group mapped 25,500 CCTV cameras across the city and found that facial recognition technology was disproportionately used in nonwhite communities in Brooklyn, Bronx and Queens.

Adams’ Blueprint to End Gun Violence plan released in January suggested expanding the use of facial recognition, along with “the responsible use of new technologies and software to identify dangerous individuals and those carrying weapons.” He explained in a press conference: “We’re looking at all of this technology out there to make sure that we can be responsible within our laws. We’re not going to do anything that’s going to go in contrast to our laws. But we’re going to use this technology to make people safe.”

Limiting the use of chokeholds by police

What was promised: Both the New York City Council and the state Legislature passed laws banning the use of chokeholds by police. The Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act, sponsored by then-Assembly Member Walter Mosley and then-state Sen. Brian Benjamin, was passed by the Legislature in June 2020. The bill made it so a police officer who injures or kills someone by using “a chokehold or similar restraint” could be charged with a class C felony, punishable by up to 15 years in prison. The council legislation criminalized “the use of restraints that restrict the flow of air or blood by compressing another individual’s windpipe or arteries on the neck, or by putting pressure on the back or chest, by (a) police officer making an arrest.” The NYPD’s own policy has prohibited chokeholds for decades, but the new law made it so that officers who engage in the practice could face a class A misdemeanor charge under the law.

Where we are now: The NYPD’s police unions sued over the legislation, and last yeara state Supreme Court judge ruled that the policy was “unconstitutionally vague” and must be rewritten. On May 19, an appeals court reinstated the law, writing the “Supreme Court should have not found the diaphragm compression ban to be unconstitutionally vague. The diaphragm compression ban is sufficiently definite to give notice of the prohibited conduct and does not lack objective standards or create the potential for arbitrary or discriminatory enforcement.”

Officers have continued to use the restraint tactic since Garner’s death, according to the New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board, which reported in January last year 40 instances in which officers have used chokeholds since Garner’s death.

Better officer accountability

What was promised: The NYPD Internal Affairs Bureau, along with the Civilian Complaint Review Board, was charged with investigating hundreds of complaints of officer misconduct during the 2020 protests. De Blasio, at the time, said he was concerned about the dozens of videos of officers behaving aggressively toward protesters, but he also expressed support for the department’s handling of the demonstrations overall. “Look, there are some specific instances I don’t accept, where there needs to be discipline,” the mayor told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer on June 5, 2020. “But the vast majority of what I’ve seen is peaceful protest that has been respected as always, and folks making sure voices heard for change, and police have shown a lot of restraint.”

Where we are now: The Civilian Complaint Review Board earlier this month reported that it has substantiated 267 of 316 cases of officer misconduct related to the 2020 protests and recommended the highest level of discipline for 88 officers. The NYPD has closed 44 of those cases and agreed with the Civilian Complaint Review Board’s recommendations just 10 times. However, the board said it faced barriers in investigating many of the complaints due to its inability to identify some of the officers seen on the video footage engaging in aggressive tactics, forcing it to close 26% of cases for that reason.Some of the officers covered or refused to disclose their badge numbers when asked by protesters – a violation of NYPD protocol under the 2018 Right to Know Act passed by the City Council. In releasing the results of the protest investigations on May 11, the Civilian Complaint Review Board said it would publish a report sometime this summer with recommendations on how to enhance the NYPD’s protest response.

“The CCRB was flooded with complaints,” interim Chair Arva Rice said in a statement about the 2020 protests. “In the height of the pandemic, our investigators used all possible resources, including thousands of hours of (body camera) footage, civilian footage, police records and more, to fairly and impartially investigate some of the most complicated cases the Agency has seen.” She said, as of mid-May, the Civilian Complaint Review Board had finalized 98% of cases and submitted its recommendations to the NYPD.

– with reporting by Jeff Coltin

NEXT STORY: Officials are raising alarms about ghost guns – here’s what you need to know about the homemade weapons