Policy

No, New York wasn’t the anti-slavery hero you thought it was

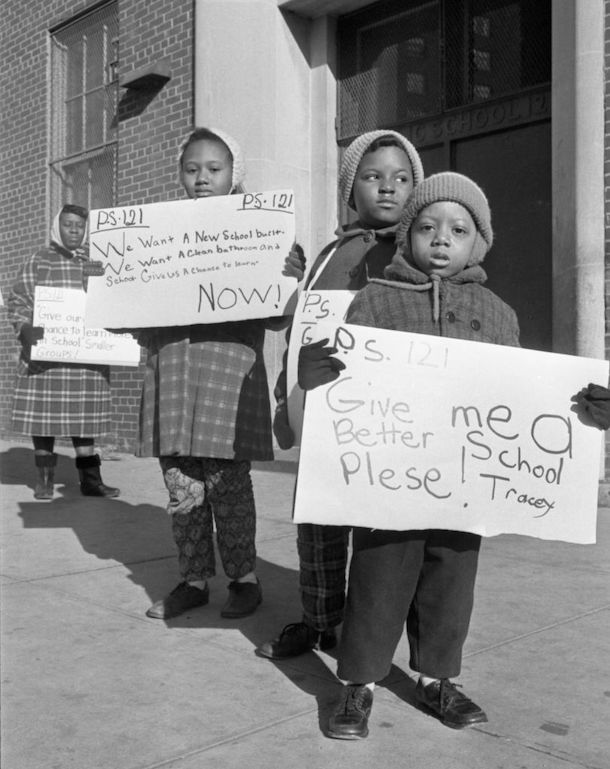

In light of the state Legislature passing a bill to create a reparations commission, a look back at history shows that the state has a lot of wrongs to make right for Black New Yorkers.

An illustration of the early days of Manhattan’s Financial District. ilbusca/Getty Images

The simplest narrative of American history portrays the North as a humanitarian anti-slavery hero in the fight for freedom and equality for African Americans. But a closer look at history will reveal something much darker.

The same beliefs of Black inferiority were expressed by political and business leaders, and the citizens who put them in charge, in both Northern and Southern states in ways that were both implicit and explicit. New York state is one of the many Northern states that has a history with slavery and anti-Blackness that’s built into the fabric of its institutions – it is just much more hidden compared to the states that made up the Confederacy.

“Whenever I walk through a street, especially in downtown Manhattan, I wonder who laid that street first? Who laid the foundations for it all? Slavery was alive and well in New Amsterdam, which later became New York. And the wealth of the city was based on slavery,” said Thomas Craemer, a professor at the University of Connecticut focusing on race relations.

State lawmakers passed a bill on June 8 that would form a state Community Commission on Reparations Remedies, with the hope of addressing how Black people continue to deal with the negative impacts of 400 years of slavery. Roughly 3.5 million African Americans live in New York, which has one of the largest racial wealth gaps in the country.

The bill, which is sponsored by Assembly Member Michaelle Solages and state Sen. James Sanders Jr., would create a nine-member commission to study the impact of slavery in the state and issue recommendations for reparations – which could lead to financial compensation and restitution for Black New Yorkers.

Similar bills have stalled for years in the state Legislature, including a recent push for reparations from state Sen. Jabari Brisport. Sanders and Solages’ compromise bill keeps all members of the commission appointed by legislative leaders and the governor, rather than outside entities, and its language said the commission’s recommendations “may include” financial compensation, rather than “shall determine” the compensation.

The bill is currently awaiting Gov. Kathy Hochul’s signature. A spokesperson for the governor has said that Hochul will review the bill.

If New York creates a commission to study reparations, it would be the second large state to do so. California created a reparations task force in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, as a response to the inhumane treatment of Black people.

“What we have done in our task force, we have created an incredibly comprehensive report that talks about discrimination, the history of discrimination in the United States, and also talks about the history of specific discrimination in the state of California, what that looks like and how it rolled out,” said Lisa Holder, a member of the California Reparations Task Force.

In March, the California task force estimated that Black Californians were owed $800 billion in reparations. Holder’s advice for New York legislators when studying reparations was to focus on how Black people in New York were impacted by all of the different stages of discrimination.

“So we have an omnibus report, but then we also have a very specific analysis within that overarching report,” Holder said. “And I would recommend to the Legislature in New York to be very New York-specific in their analysis, focus on the history of discrimination since New York became a state, which was at the beginning of the creation of the Union.”

New York’s concealed history with slavery and racism

Slavery in New York dates back to the 1600s. According to the New York Historical Society, 41% of New York City households had slaves during the Colonial era. The economy was largely built by Dutch and English merchants around supplying ships for the slave trade and in selling crops that slaves produced, such as sugar, tobacco, chocolate and cotton.

“The problem is the history is very hidden in New York, and it took decades to find the African Burial Ground and to build proper monuments,” Craemer said. “Then there is a mansion, the Morris-Jumel Mansion, that is the oldest building in New York where slaves were also kept. And yeah, there’s very little in the exhibit about (New York’s history with slavery). But once you start digging into it, it’s everywhere.”

In New York state, by the 1800s, almost every businessperson had a stake in the slave trade. New York-based banks sold securities that would fund expanding slave plantations. And large, well-known insurance companies, which still operate today in the state, sold policies to slave owners that would ensure compensation if slaves were killed or injured.

A few of the large companies in the state that profited off of slavery confirmed by the United States Citizens Recovery Initiative Alliance and other sources include: Aetna, JPMorgan Chase & Co., New York Life Insurance Co., Domino Sugar, United States Life Insurance Company of New York, Citibank, Brown Brothers Harriman, Tiffany & Co., Columbia University and Advance Publications.

Even after legal slavery was finally abolished in 1827, the beliefs of Black inferiority remained embedded in the institutions of New York state. When the federal Civil Rights Act became law in 1875, which guaranteed the equality of African Americans and prohibited discrimination in public institutions, Black New Yorkers would use it to challenge discriminatory practices in the state.

In 1883, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was ruled unconstitutional in New York after a series of five cases, known as the Civil Rights Cases, where acts of discrimination against Black people regarding public accommodations were brought to the U.S. Supreme Court. This ruling opened the door for private citizens to discriminate against people of color.

The New York State Bar Association’s Task Force on Racism, Social Equity and the Law released a report this year that studied the racial wealth gap in the state. Lillian Moy, who is a co-chair of the task force, highlighted some of the laws that enforced segregation.

“I was surprised to learn that in some of the boroughs, that local laws, which determine a lot of how schools operate, they allowed separate but equal schools in post-Reconstruction,” Moy said. “And it was held up in Brooklyn, in the late 1800s, but it took new legislation to end educational segregation in around 1900. And still, that allowed rural school districts outside of the cities to continue to run segregated schools. And during this period, of course, housing continued to be largely segregated in a variety of ways.”

You can still see the ripple effects from those laws today in the city. In New York City public schools, 83% of Black students attend a school that is 90% nonwhite, and 34% of white students attend a school that is over half white. New York City has the most segregated schools in the nation for Black students, and one of the main causes is segregation in neighborhoods. A total of 95% of Black residents in New York live in a county that is highly segregated from white people.

Practices like redlining, which started in the 1930s, where neighborhoods in New York City that contained Black residents were deemed “hazardous” and not worthy enough for investment, also had visible impacts that’s still present today. Areas in Harlem and Washington Heights, which were redlined neighborhoods, still suffer from poorer living conditions compared to the areas that were greenlined around Central Park and midtown Manhattan, which still contains a large number of white residents.

The reparations debate

Although creating a reparations commission in the state has garnered support, including from New York City Mayor Eric Adams, debates on what reparations should look like and who should receive them are more difficult and nuanced.

“I don’t see it as just a one time, here’s, you know, half a million dollars or $200,000, to every Black person who descended from slavery,” said Annette Wilcox, a volunteer at The United States Freedmen Project, a nonprofit organization. “I see something where the goal is to undo the damage that was done that has reduced the position of the American freedmen in the state.”

According to Holder, reparations should have five key components: compensation, restitution, apologies or atonement, guarantees of nonrepetition, and rehabilitation.

“What that means in real language is that not only must there be some meaningful act of apology and atonement, which constitutes monetary compensation and redress for the harms,” Holder said, “but also, and most importantly, we have to rehabilitate the systems and the structures that have institutionalized anti-Black discrimination and created the pathways for all of these horrific outcomes that we’re seeing in every sector for Black people.”

For the New York State Bar Association, knowledge and understanding of the harms done to Black people in the state and a weighing of different remedies is preferred over reparations.

“We don’t recommend reparations, personally. What we want is the study. Because building understanding, knowledge and the political will, you have to bring people information,” Moy said.

Reparations in America in the past have either involved a form of financial compensation or an apology from the U.S. government. After World War II, where about 150,000 Native Americans supported the war effort, the U.S. government sought to compensate Native Americans for the harms the United States caused throughout its history, which included seizing their lands and killing their people.

In 1946, the government formed the Indian Claims Commission to sort out reparations, which resulted in $1.3 billion to be set aside and distributed to 176 Native American tribes and organizations.

Also, after 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 served as a form of reparations for Japanese Americans, which gave them each $20,000 and an apology from then-President Ronald Reagan.

Moy said the reparations paid to Native Americans and Japanese Americans was insufficient.

“How do you compensate Native Americans for the deliberate extinguishing of their culture, that it was wrong to speak their languages and practices, and engage in cultural practices and the seizure of land, and deliberate killing?” she said. “So how do you compensate for that much wrong? Similarly, how do you compensate for slavery? Jim Crow? For redlining? And for the consequent loss of opportunity and the ability to advance?”

Determining who should receive reparations in the state will be another point of debate, since not every Black person in America has lineage that ties back to slavery in the country, but they still deal with the effects of it in their everyday lives.

“It’s currently the most controversial point. It was a huge issue in California, and a very controversial issue until the task force voted for the lineage-based model,” Craemer said.

Craemer said there were two different arguments that appeared during discussions on who should qualify for reparations. The first one was to make the community of eligibility as large as possible so it can create political solidarity. The other argument was to stay focused on those who have lost the most historically, which are the heirs of enslaved people in the United States. According to Solages, her reparations bill will include a study of lineage-based reparations.

“The argument of the lineage-based advocates is that people who immigrated into the United States had a choice. They knew what the racial hierarchy is in the United States before coming,” Craemer said. “If they came, they did so because they wanted to benefit from the economic down payment that U.S. slavery provided to the U.S. economy. So in a way, they already had a benefit from slavery by pursuing the opportunities in the United States and often opportunities that the descendants of the enslaved don’t have.”

To Wilcox, it’s important for any reparations legislation in New York state to be focused on specific injuries to specific people.

“When the slavery ended in 1865, and the Freedmen’s Bureau was formed, there was an agreement that the ex-enslaved people will get 40 acres and a mule. That’s a true statement and basically what has happened by 1877 when (the) Reconstruction era was over, and that’s basically when they pulled all of the troops out of the South and kind of left it to the ex-confederates, who then instituted all the Jim Crow laws and segregation and violence,” Wilcox said. “And so, the reparations claim is based on that. And we’re now in 2023. And so at this point, yes, it’s way overdue. But it’s still due to that same population of people whose ancestors were enslaved.”