In Albany, where a number of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s policy priorities have succumbed to resistance from Gov. Andrew Cuomo and state Senate Republicans, documents suggest that de Blasio has turned to the real estate industry’s chief lobbying group in New York as an intermediary to press politicians on a matter beyond its traditional scope: the city’s public school system.

The de Blasio administration sought help from the Real Estate Board of New York in 2015, when the city was engaged in a protracted debate with state officials over whether mayoral control of city schools should be extended long-term.

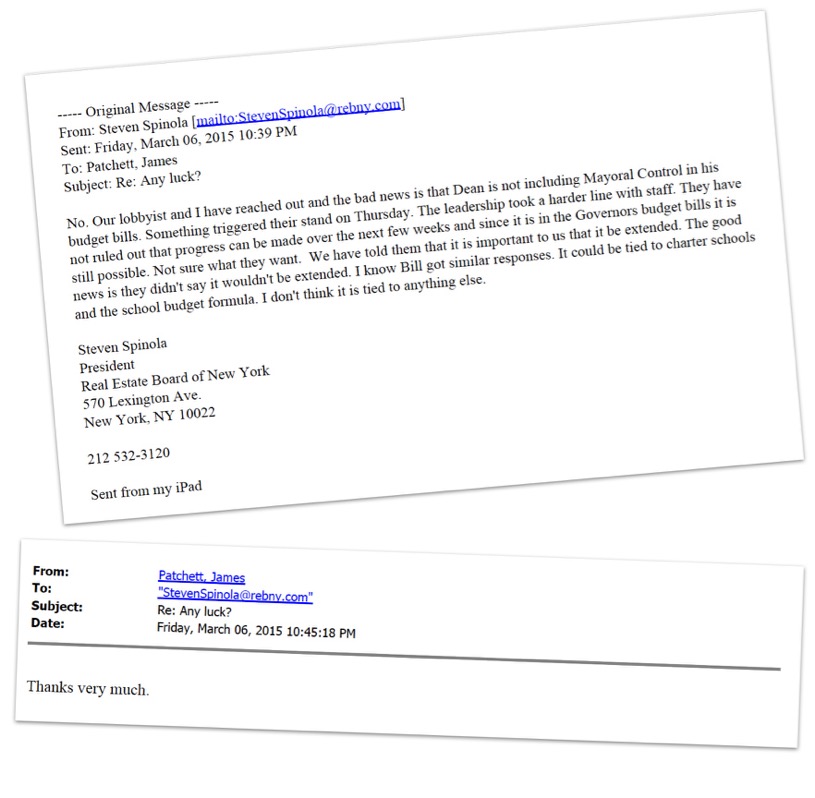

Responding to an email from a New York City deputy mayor’s chief of staff, then-REBNY President Steven Spinola wrote in March of 2015 that it did not appear as if the state Senate majority leader at the time, Republican Dean Skelos, had put anything about school governance in his budget bills.

Here is an excerpt of the email exchange between Spinola and James Patchett, the chief of staff to Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development Alicia Glen, obtained through a Freedom of Information Law request:

The de Blasio administration continued to seek REBNY officials’ assistance in Albany as well as their input on city policy, according to a review of additional emails exchanged between the two offices during the first half of 2015.

The correspondence reflects a close relationship and suggests City Hall and the real estate lobbying group have grown accustomed to collaborating. Emails show staffers socialize together. REBNY was able to secure Glen as a speaker at a banquet. The trade group helped a national real estate group extend an invitation to de Blasio for its board meeting by putting him in touch with an administration contact. And one of REBNY’s several lobbyists on staff at the time planned to lunch with an advisor to a deputy mayor that she communicated with about various projects and policies.

City and REBNY officials also discussed development plans. When REBNY members’ projects seemed to stall in “regulatory purgatory,” Angela Sung Pinsky, then the group’s senior vice president for management services and government affairs, sought guidance from the mayor’s staff and received prompt replies. And the administration and REBNY collaborated on city policy matters, including their shared goals of passing a revamped version of the 421-a tax abatement, which was used to spur the construction of residential buildings with affordable apartments, and a more long-term extension of mayoral control.

REBNY spokeswoman Nicole Chin-Lyn said the trade group has consistently advocated on matters of importance to the city’s well-being, including its education system. “Given the strong interrelationship between the economic success of the city and the health of its real estate industry, and that REBNY is one of the city’s leading trade associations, the organization historically has spoken out on matters of important public interest, like mayoral control of NYC public schools,” Chin-Lyn said in a statement. “REBNY and its lobbyists have made all appropriate disclosures with respect to its lobbying activities.”

When asked about leaning on REBNY during the mayoral control fight, de Blasio spokesman Austin Finan pointed out that a range of New Yorkers and city institutions supported the mayor’s request that the state Legislature grant the city executive long-term control over the school system. Indeed, de Blasio collaborated with former GOP Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, the business group Partnership for New York City and the heads of several community groups on the issue. Finan said the administration checks in with all such stakeholders on matters of importance to the city, as it did with REBNY on mayoral control.

“The strength of our education system is essential to the overall health of the city, so it’s no surprise that the city’s business community made its voice heard in Albany to ensure that mayoral control was extended and our schools were kept on the right track,” Finan said in a statement. “Whether through traditional lobbying or more outward-facing public affairs tactics, a broad coalition of business leaders, nonprofits, clergy, labor unions and elected officials did its part to push Albany for an extension. The administration is in regular contact with all stakeholders associated with the issues facing our city.”

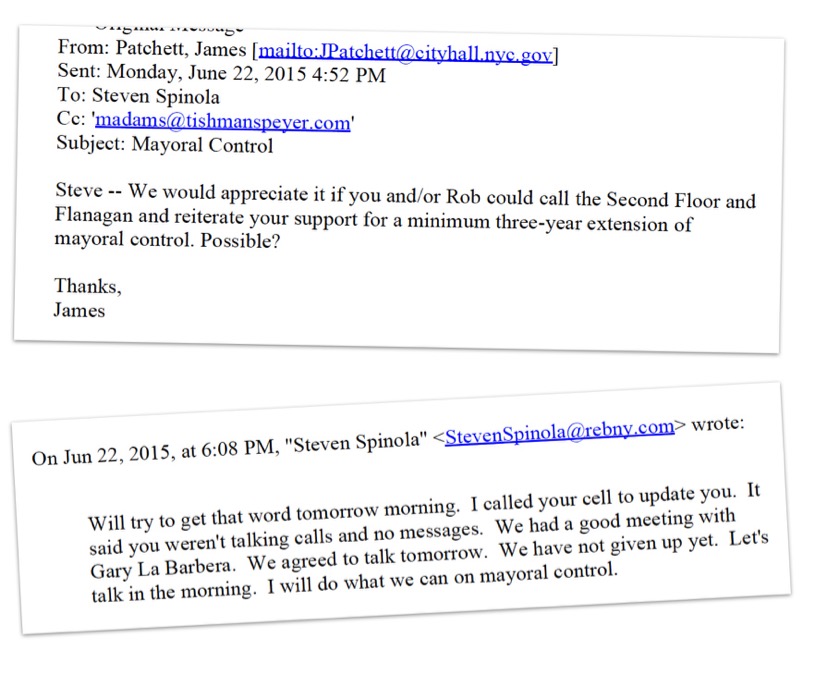

The administration touched base with REBNY about mayoral control again when the state legislative session was winding down in June 2015. At that point, Patchett requested that REBNY express support for a three-year renewal to the governor’s office and to the new state Senate GOP Majority Leader John Flanagan. In a little over an hour, Spinola replied that he would do what he could on mayoral control.

Here is an excerpt of the exchange between Spinola and Patchett:

When the legislative session ended, de Blasio was granted a one-year extension at the helm of city schools. In 2016, it was again extended for a single year.

In his response to Patchett at the end of the 2015 session, Spinola added that he had been unable to reach Patchett to update him on negotiations with Gary LaBarbera, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, presumably over the 421-a tax abatement that was set to expire shortly. The Building and Construction Trades Council had been promoting the use of union labor on 421-a sites, but had expressed that it could be flexible in only requiring this in geographic areas where it seemed economically feasible or having workers accept a lower prevailing wage rate. Patchett sent emails attempting to coordinate a call with Spinola.

The state passed a six-month renewal of the 421-a abatement, which the de Blasio administration believed would prove critical to achieving its goal of creating 200,000 units of affordable housing within a decade.

At the behest of Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who has insisted on tying prevailing wage standards to a government subsidy, the state tasked REBNY and the Building and Construction Trades Council with reaching an agreement on wage standards for construction workers by mid-January of 2016. If they succeeded, the 421-a extension would automatically be extended for four years; if not, the tax benefit would expire. When REBNY and the construction union leaders failed to reach an accord, 421-a lapsed, a development that emails show the real estate group and City Hall spent months trying to avoid.

Exchanges between the mayor’s office and REBNY leaders suggest the industry trade group and the mayor’s team coordinated on plans for a specific public relations pitch to promote the mayor’s proposed changes to 421-a. For instance, when REBNY released a report shortly after requesting data from the city on the housing generated by 421-a, the mayor’s director of intergovernmental affairs, Emma Wolfe, let the group know that she would have preferred to have been given a heads up before it was sent to reporters. John Banks, who was selected to succeed Spinola as REBNY’s president, replied that the analysis, which found that the loss of 421-a would skew the housing market toward production of condos rather than rental apartments, seemed in line with the PR strategy he and de Blasio’s team had discussed.

And when the debate over 421-a heated up in Albany in 2015, City Hall reached out to Spinola, Banks and James Whelan, REBNY’s executive vice president, to see if the group could get state lawmakers to call reporters writing about the abatement. On June 10, Patchett, Glen’s chief of staff, wrote, “Apparently no senators have yet reached out to Dawsey at wsj,” referring to a Wall Street Journal reporter. “Any way we can make that happen ASAP?” After a back-and-forth, Whelan wrote that state Sen. Phil Boyle called and left a voicemail, but would try again. The REBNY executive also noted that he would text state Sen. George Amedore himself, rather than go through an intermediary.

Days before the legislative session concluded, Spinola was sending Patchett what appears to be REBNY’s specific legislative text suggestions, although the wording Spinola sent along does not appear to have made its way into any legislation introduced or passed in Albany. At the time, de Blasio and REBNY were pushing for a 421-a revamp that would have required any building in the city that received the tax benefit to reserve some units for affordable housing, as opposed to simply imposing it in parts of the city. They also sought to expand the portion of building units that must be maintained below market rate, to stop allowing condominium projects to receive the abatement, and to extend the life of the benefit. Excluding pay provisions for projects in Manhattan and along the waterfront in Brooklyn and Queens, much of the revived 421-a framework that Cuomo is currently pushing includes de Blasio’s and REBNY’s original suggestions.

A city representative said people in the state Capitol made it clear to the administration that any 421-a plans it pitched would need the backing of REBNY to succeed. This need for a conduit may have been particularly relevant in the Republican-led state Senate, which seemed reluctant to consider the mayor’s proposals after de Blasio and his allies attempted to help the Democrats take control of their chamber during the 2014 elections. This dynamic was not lost on de Blasio’s team, as evidenced by Patchett’s seemingly sarcastic comment to REBNY officials that Boyle gave a “tremendously helpful” quote to the Wall Street Journal reporter they wanted him to speak with. In the article, Boyle said he didn’t believe de Blasio had any fans in the Republican caucus and that his political activities in 2014 didn’t help.

“The administration worked closely with all stakeholders toward delivering an improved 421-a that eliminated condos from the program and strengthened affordable housing requirements,” de Blasio spokesman Austin Finan told City & State. “It was made clear to the administration very early on that Albany was prepared to renew the old, broken program, and that the only chance for significant reforms required working with leaders in the real estate sector. While we had significant policy disagreements, we were successful in building support around expanded affordable housing requirements that would ultimately double the affordable housing delivered through the program. The reform legislation we secured remains the basis of the current 421-a negotiations that we are hopeful will revive this critical tax abatement program and spur the development of affordable housing our city desperately needs."

Chin-Lyn, the REBNY spokeswoman, said it was widely known that the real estate trade group worked with the administration to try to resuscitate a tax abatement seen as critical to the administration’s ambitious affordable housing agenda. “It is common knowledge that the de Blasio administration and REBNY negotiated a reformed 421-a program that many expect will produce significantly more below-market rental housing units throughout New York City,” she said in a statement. “The two organizations then continued to work together toward the implementation of that plan.”

Although it was no secret that de Blasio worked with REBNY on his 421-a plan, some construction union leaders said they had not been aware of how deeply the two collaborated until they reviewed these email exchanges. LaBarbera and representatives of construction labor management funds, which advocate for companies that use organized labor and related unions, said it was clear the real estate lobbying group had more sway at City Hall than they did, given that they were not invited into the 421-a discussions the administration and REBNY had engaged in.

“Instead of reaching out to union leaders to gain consensus on an affordable housing program that ensures middle-class wages for workers, (de Blasio) coordinated with a lobbying group – led by billionaire developers – to run an anti-union campaign that would lead to unsafe job sites and a low-wage workforce,” The Greater New York Laborers-Employers Cooperation and Education Trust and the New York City and Vicinity Carpenters Labor Management Corporation said in a joint statement. “Thankfully Governor Cuomo and Legislative leaders like Speaker (Carl) Heastie, Senate Majority Leader Flanagan and numerous members stepped up to stop the mayor and REBNY's plan from undermining the working families of this city. We stand by our original campaign – massive billion dollar public subsidies have public responsibilities and the construction workforce deserves to be able to afford to live in the city in which they work.”

LaBarbera said he sensed de Blasio had opposed incorporating prevailing wages into 421-a, and he now believes the foundation for the mayor’s position came from REBNY. “The mayor made his position clear, as well, that he wasn’t in favor of wage standards because of the belief that wage standards would reduce the production of affordable housing. And it’s clear now that a lot of the basis of this position is really from REBNY’s analysis,” LaBarbera said. “REBNY clearly has significant influence at City Hall … however, the governor has our back and stands up for the principles that we believe in. REBNY didn’t succeed in essentially carving us out with all of this data that, again, I think is created and manufactured, and not really based in fact.”

There is no discussion of prevailing wages in the email exchanges until more than a week after the de Blasio administration released its 421-a reform plan on May 7. And once the topic comes up, the emails do not provide much clarity on where the de Blasio administration stands on pay rate provisions. REBNY also forwarded the results of a poll that found voters oppose a prevailing wage provision that would cut into 421-a’s ability to generate affordable housing, and there was no reply from the de Blasio administration. In response to a City Hall data request, REBNY sent a chart showing wages and benefits are more costly for construction workers earning prevailing rates versus those making average salaries and benefits in the New York-New Jersey metro area. Again, the documents do not include any reactions from City Hall on the information it received.

De Blasio’s office disputed the idea that REBNY influenced the administration’s thinking on prevailing wages. Finan, the mayoral spokesman, said in an email, “Finding the balance between good wages for workers and ensuring that the construction of affordable housing is economically feasible has been our sole guiding influence in prevailing wage discussions.”