Eric Adams

“Go back to Iowa” could fit Adams’ mayoral strategy

Progressive transplants have other candidates, so the Brooklyn borough president is looking elsewhere for votes.

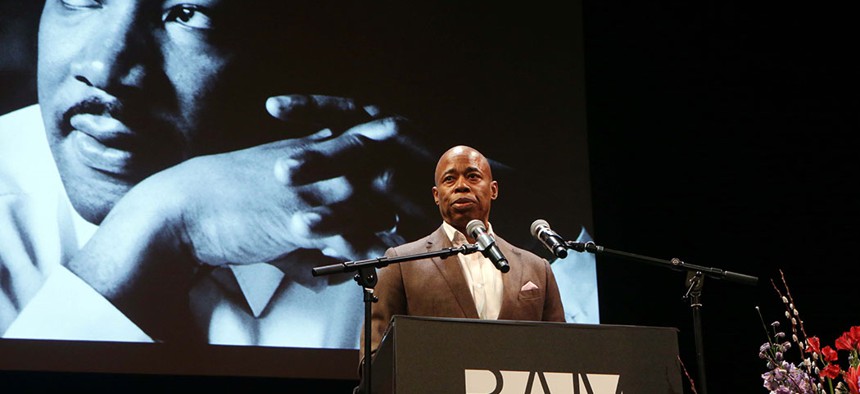

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams at the 34th Annual Brooklyn Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. MediaPunch/Shutterstock

On Wednesday morning, before the political and economic power brokers at an Association for a Better New York breakfast, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams admitted that he made a mistake on Monday when he inveighed against gentrifiers at the National Action Network’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day rally: “The sentence was a gaffe,” he assured the audience.

But were Adams comments a misstep, or do they – along with his friendly presentation to a centrist, pro-business organization two days later – fit right into his 2021 mayoral campaign strategy?

New York City is only 35% white, and there already are two white candidates from Manhattan – Comptroller Scott Stringer and Council Speaker Corey Johnson – who are well-positioned to appeal to the young gentrifier class, having backed some of its preferred insurgent candidates. Instead of competing with them for that vote, Adams may have a lot more to gain by appealing to working-class and middle-class New Yorkers of color.

At first glance, shouting “Go back to Iowa! You go back to Ohio! New York City belongs to the people that was here and made New York City what it is,” as Adams did on Monday, is an odd look for the ex-Republican former cop.

But, in a weird way, it works. While progressive transplants on Twitter derided Adams for sounding like a nativist, he hit notes that might simultaneously appeal to both conservative whites and many black New Yorkers by uniting them around something they can agree on: that the people who came here after them are the worst.

Adams’ mayoral pitch could emphasize the fact that he was here through the bad old days. Born in Brooklyn and raised mostly in Queens, Adams wasn’t just here, he was a part of the turnaround. He served in the NYPD while crime rates fell from record highs, and he put down roots, buying homes in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Prospect Heights that have skyrocketed in value. It’s a story that could appeal some of the city’s older and more moderate Democrats, and Adams hasn’t been shy about that. When he famously said, in a private meeting, that he would “out-white” his mayoral rival, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, Adams wasn’t talking about about the white progressives, many of them transplants, who helped elect Democratic Socialist candidates like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and state Sen. Julia Salazar. Adams was talking about outer-borough white voters in neighborhoods like Bayside, Bath Beach and Bensonhurst – many homeowners like him, who might worry about the crime rate rising or their property taxes soaring.

“I know I’m a New Yorker! I protected this city!” Adams said at NAN on Monday. “I have a right to put my voice in how this city should run!”

Voters are going to be intrigued by Adams’ comments, political strategist Basil Smikle told City & State. “Race and class are inextricably connected to gentrification and the changes that we’re seeing in the city right now. So there may be another way to say it, or another way to spin it, but I think the substance of it is real,” Smikle said. “It starts a dialogue that, even if unevenly embraced initially, I think it will get traction down the road.”

While Stringer and Johnson are battling it out for the 2021 support of the growing progressive electorate that seems tied to much of the city’s change, Adams’ comments on Monday are just the latest sign of him potentially ceding that ground to them. Last month, at the opening of a senior center for poor and LGBT New Yorkers Adams said, “I can’t celebrate a building that is not going to be inclusive.”

Adams may have little to lose with this rhetoric. “Who is it going to turn off? Progressives, who (Adams) is not going to get anyway,” one Democratic insider told City & State, referring to Monday’s speech to NAN. “I don’t think it really hurt him all that much.”

Adams’ MLK Day comments weren’t targeted directly at conservative whites, but at a population of longtime residents, many of them black, that may have similar and overlapping anxieties: losing political power, and possibly a home, as the city changes.

Taken literally, Adams’ initial statement mistakes the prime driver of population growth and demand for housing citywide, which is foreign, not domestic, in-migration. Nor do transplants typically come from the Midwest. Domestic migrants come to New York City mostly from its own suburbs, in-state and in New Jersey and Connecticut, and from big states such as Florida and California. But New Yorkers leave for those same places in even greater numbers. As Kay Hymowitz noted in the Daily News, “the Department of City Planning estimates that between 2010 and 2018, the city saw a net 768,306 New Yorkers leave the city, while 479,960 arrived from foreign shores. Thirty-seven percent of New York City residents are foreign-born. That number also applies to Brooklyn, Adams’ home borough.” Overall, the city has become less white and more Latino in recent decades.

But in specific neighborhoods, including Adams’ own Bed-Stuy and NAN’s Harlem home, demographic data or a walk around makes clear that mostly white, white-collar newcomers are driving up the cost of living and changing the community’s character. And the cheers of the crowd at NAN – almost exclusively black New Yorkers, most of whom had likely been in the city a long time – proved it.

Like any politician, Adams knows how to tailor his pitch to the crowd in front of him. The crowd at Wednesday’s ABNY breakfast skewed much whiter than at NAN, and likely much wealthier. Adams defended his comments saying there was “real pain on the ground” and “a real concern on what gentrification is doing for this city,” but it wasn’t about race.

“Gentrification is not a color. It’s a mindset,” he said. “You can’t be Christopher Columbus and believe that you discovered New York. We were here.” Like at NAN, the remarks earned Adams loud applause.

NEXT STORY: Can Cuomo’s budget co-opt his critics?