New York City mayoral hopeful Curtis Sliwa claims he is the only candidate appealing to the city’s animal lovers. Sliwa, a parent to six cats, will appear on the November ballot twice: on the Republican Party line and on an independent ballot line he created called Protect Animals.

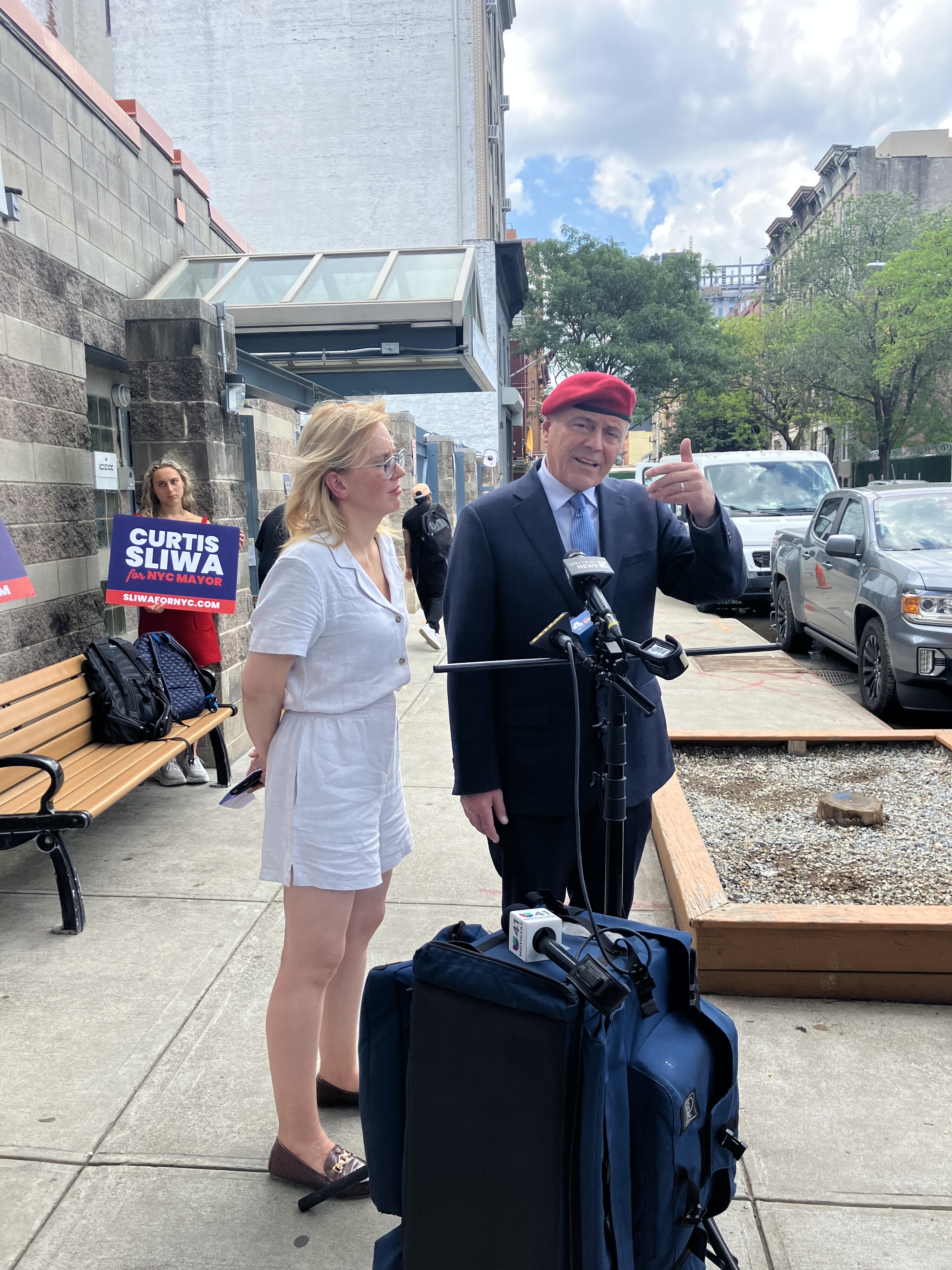

“Ninety-seven percent of Americans now, whether they voted for Trump or Harris or they’re apolitical, actually view pets as family members,” he said last month, wearing his trademark red beret and standing next to his wife, Nancy, on a shaded sidewalk outside an animal shelter in East Harlem. Behind him, stressed-out looking people stood at the shelter doors with leashed dogs. Sliwa was there because Animal Care Centers of New York City had recently suspended its new animal intake while the shelter network scrambled to deal with the 1,000 animals – including more than 380 dogs – already crowding its facilities.

Suddenly, the Sliwas were interrupted by a very loud shirtless man wearing athletic shorts and wireless headphones, who ran through the assembled gaggle, apparently on his morning jog. “Clean up 110th Street! There is dog shit all over the street!” he yelled, clapping his hands for emphasis. “Clean up the dog shit, Curtis!” Neither Sliwa acknowledged the interloper, but his contribution felt relevant.

Dogs, New York City’s most visible pets, are an inescapable part of public life. They fill our parks, poop on our sidewalks, pee on our trees, pant next to our al fresco tables, bark at us on the train. Whether we own one or not, we find them in our workplaces, our gyms, our apartment buildings. We read daily headlines about the conflicts they cause and about the abuse they are subject to. As Sliwa noted, many New Yorkers think of them as family members, and more specifically, as their children. As attitudes about dogs’ proximity to personhood continue to shift, the law – and the elected officials who write the laws – are coming to view them as a constituency of sorts, one deserving of substantial public resources.

There is no official city dog census, but the most recent New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, taken in 2023, found that about 530,000, or 15%, of New York City households had a dog. An average of about 85,000 dogs have been licensed in the city each year for the past decade, with a notable spike during the pandemic.

Pet ownership is indisputably an economic force. Americans are expected to spend $157 billion on pet products and services this year, according to the American Pet Products Association – a figure that continues to climb despite economic uncertainty. On the apartment rental platform StreetEasy, 76% of New York City apartments now allow pets, up from 72% last year, and “Pets allowed” was the third most-searched amenity behind in-unit laundry and a dishwasher. There are already at least two luxury dog clubs in New York City, with another Los Angeles-based company, Dog Ppl, slated to open one in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in the late fall. Perks of membership include manicured lawns, training and grooming, Wi-Fi and coffee and cocktail bars (for humans). Dog owners are increasingly likely to travel with their pets – enough to support a pricey dog-centered airline called Bark Air that launched last year and is based in New York.

At least one dog is present in the halls of power. First Deputy Mayor Randy Mastro recently adopted Kato, a standard poodle mix, who is now running around City Hall making the mayor jealous. “There’s no greater loyalty than in a dog,” Mayor Eric Adams recently said. “I want a dog so bad, but being mayor, you know, dogs like a lot of attention.”

“A pet such as a dog is not just a thing”

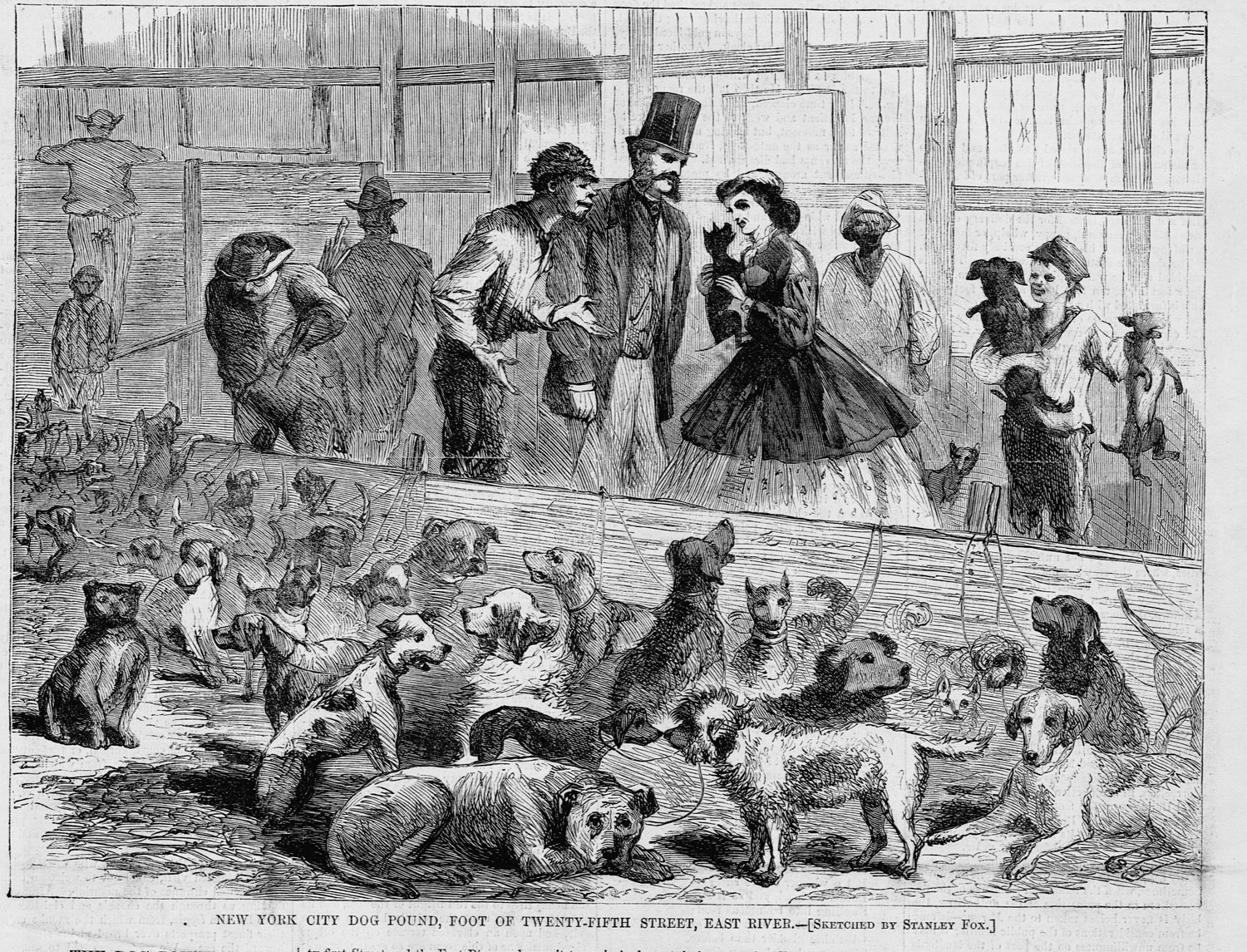

New York City has long grappled with how to manage dogs – and things used to be dire. In the late 1800s, as the forces of industrialization pushed animals and humans into extremely close urban quarters, feral and pet dogs alike freely roamed the streets. As historian Ernest Freeberg writes in “A Traitor to His Species,” a biography of animal rights pioneer Henry Bergh, there was no system to sterilize dogs until the 1930s and no way of warding off fleas. People feared that the intense heat of July and August – “dog days of summer” – caused the packs of dogs teeming throughout the city to go mad with a terrifying disease that was then called “hydrophobia.” (The origin and transmission of rabies was still a mystery then.)

The city was desperate to control its dog population, and its solution was brutal. Every summer, groups of boys and men rounded up dogs and brought them to a crowded pound where they were held for a day or two in case an owner might show up to claim them. After that, the remaining dogs were crammed into an iron cage 50 at a time and submerged in the East River for 10 minutes. Hundreds of dogs could be killed this way in a single afternoon.

Even Bergh, who founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, acknowledged the need to curb the dog population, and he actually advocated for the river drowning method as the most humane. But he also initiated a cultural conversation in which we continually assess to what extent animals can experience suffering, and what trappings of personhood are owed to them.

“If you go back maybe 150 years, dogs really throughout the United States were essentially indistinguishable from property, from a piece of furniture, for example,” said Christopher Berry, executive director of the Nonhuman Rights Project, which advocates for animals’ legal rights. “New York actually really led the way with anti-cruelty laws and Henry Bergh in the late 1800s, so that’s where the legal status really starts to change.”

In more recent decades, both the courts and lawmakers have inched animals further along on the spectrum of legal status from “object” toward something more like “person.” In 1979, after an animal hospital lost a dog’s corpse, Queens Civil Court Judge Seymour Friedman ruled that the dog’s owner was owed damages beyond just the market value of the dog. As Friedman wrote, “a pet such as a dog is not just a thing.” Since 1996, New York’s estate laws have allowed people to leave behind a trust to provide care for their pet. And since 2021, state law requires judges to consider the best interest of pets in divorce custody proceedings, reasoning that, “for many families, pets are the equivalent of children.”

In July 2023, a woman crossing a Brooklyn street watched in horror as a car rounded the corner and crushed the dog she was walking. In a landmark June decision, state Supreme Court Justice Aaron Maslow ruled that the dachshund named Duke should be considered a family member rather than property and that emotional distress damages were owed. (The driver has appealed.)

A flurry of recent proposed legislation reflects the evolving view that our pets are members of our community in their own right. A City Council bill introduced last year by Council Member Shaun Abreu would expand paid leave to people who need to miss work to care for their sick pet. City Council Member Bob Holden introduced a bill to establish a pilot food pantry for pets. The Protecting Animals Walking in the Street (PAWS) Act, sponsored by state Sen. Andrew Gounardes, would increase penalties for drivers who hit a pet. This year, the state Senate passed a package of bills that would, among other things, raise the maximum prison time for animal cruelty. In 2024, the city Department of Homeless Services, together with the Urban Resource Institute, piloted a homeless shelter that allowed pets. Assembly Member Linda Rosenthal has a bill that would declare that animals entitled to humane treatment under the law and can therefore be victims of crimes. “The Legislature finds and declares that animals are sentient beings,” her proposed bill says.

Dog fights

Dogs can have many benefits for city dwellers. They’re a balm for their owners’ mental health and they get people walking outside, improving physical health and getting more eyes on the street, which contributes to a greater sense of public safety. In a city full of AirPods zombies who only talk to people they’ve previously arranged to meet on an app, dogs are one of the best vectors of spontaneous connection we have.

But they can also be the nexus of some pretty extreme neighborhood drama.

In May, two pit bulls named Rambo and Zooey attacked a Chihuahua mix named Penny on the Upper West Side. Penny’s guardian said both pit bulls lunged at Penny, and one chomped on her and refused to let go as multiple other bystanders piled on to try to pry their jaws apart. Penny required surgery, the pit bull owner was evasive and the community was in an uproar. “The result of Joey Columbus’ two dogs biting, ostensibly, Lauren’s Chihuahua, that set people off,” said Upper West Side Council Member Gale Brewer, naming the two owners she’s now spent countless hours thinking about. “And we ended up, I think we had 500 or 600 people, maybe more, at Goddard Riverside two days later,” Brewer said of the ensuing town hall. It turned out that Rambo and Zooey were accused of previously attacking and killing another dog. The attacks inspired legislation from Queens Assembly Member Jenifer Rajkumar that would create new criminal offenses: negligent handling of a dog and reckless handling of a dog. “Right now in New York, if your dog mauls another dog, there’s almost no penalty,” Rajkumar said. “Negligent owners walk away while innocent dogs sometimes die.”

The Penny situation was just one recent clash. Any New Yorker knows what you mean when you refer to “the Central Park birdwatching incident,” which notoriously involved a frantic dog owner and spurred a reckoning over racism during the heart of the COVID-19 lockdown. A couple years after that, the Park Slope neighborhood was divided over how law enforcement should get involved after a man who seemed to be homeless and dealing with mental illness struck a leashed dog with a staff in Prospect Park, and the dog, Moose, later died. “It was tragic,” said City Council Member Shahana Hanif, whose district includes the park, three years later. “It is something that I, like, I think about, you know, I can’t just leave it behind, and it should have never happened.”

More common are the minor squabbles and complaints that come with living in such close quarters: barking and poop. There are many, many people who do not wish to be living in a city of dogs. That is evident in a few recent headlines: “New Yorkers are turning on dogs; what’s a dog owner to do?” New York Groove asked last spring. “Why Does Everyone Hate My Dog? In a city bubbling over with rage, pets – and their owners – are enemy No. 1” declared an essayist in The Cut around the same time. “Dog Parks Are Barely Holding This City Together,” wrote Curbed last summer.

The dog mayor

In late January in front of City Hall, Simon, a basset cattle dog, took the oath of office. His inauguration as New York City’s second dog mayor was attended by Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani, then a long-shot mayoral candidate. (In a vivid snapshot of the times, the very online dog mayor election was marred by a cryptocurrency scandal.) The title is honorary, and Simon has no official duties, but the existence of a dog mayor does point to a legitimate governance question the city has struggled to answer: Who is in charge of the dogs of New York?

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene issues dog licenses and oversees dog shelters, while the Department of Sanitation responds to dog poop complaints and issues fines, the Parks and Recreation Department builds dog runs and the NYPD responds to abuse calls. The city contracts with Animal Care Centers of New York City to run the shelter system. “What I had found was that each agency had sort of an unlisted animal guy, but typically their official role was something completely unrelated,” said City Council Member Justin Brannan. “It was like, ‘Oh yeah, talk to Joe at DOT, he really likes animals.’”

In 2019, Brannan passed a bill to establish the Mayor’s Office of Animal Welfare with the intention of bringing the city’s animal-related concerns into one portfolio. Initially, Brannan proposed a full-fledged city department for animals, but the bill was watered down to a single office – the first in the nation – which is now staffed with just one (very dedicated) person and has a budget of less than $100,000. Sliwa, the Republican mayoral nominee, is proposing an “agency in the basement of City Hall” dedicated to animal welfare. “It’s going to be a whole agency, rapid response, to deal with all animal-related issues,” Sliwa said.

The dog oversight question extends to one of their biggest imprints on city infrastructure.

The city’s 91 dog runs are currently maintained by volunteers and community groups. The parks department will not build a dog run unless there is already an established group committed to taking care of it. In 2022, Brooklyn City Council Member Lincoln Restler dealt with the outbreak of a disease that killed at least four dogs and was possibly connected to drainage problems at a popular Williamsburg dog run. Restler has a whole citywide dog run platform that includes a City Council bill to require the parks department to take more responsibility for the upkeep of dog runs and another bill requiring the department to identify five areas in every community district that could potentially host a dog run.

“In a neighborhood like this one, you have people who have both the means to invest a little bit more in the dog run and the time to care for the dog run,” Restler said on a recent morning at Hillside Dog Park in Brooklyn Heights. The vast, shady dog run abuts the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. “But in lots of parts of the city, you don’t have the same concentration of people who have excess resources and capacity to maintain dog runs in their neighborhood.”

Walking around the newly redone Washington Park Dog Run in Park Slope, where renovations cost about $650,000, Hanif pointed out some of the necessary elements. “You need doggy turf specifically meant for dogs. We allowed some areas to be fenced in so that smaller dogs can play, and then we have that water fountain,” she said, gesturing to a central spigot.

“Dog owners feel a great deal of conviction that their dogs need a place to run around, and many of the other park users feel a healthy amount of outrage that their grass is getting torn up and there’s dog poop and even safety concerns,” Restler said. In other words, in a city overrun with very spoiled dogs, the fenced-off dog runs are peacekeeping tools.

There is no poop fairy

Since the city passed its pioneering “pooper-scooper law” in 1978, there is one type of dog owner everyone in the city, whether they own a dog or not, disdains. Gothamist reported that 311 complaints about dog poop have steadily increased each year since the pandemic, with the worst offenders plaguing a ZIP code in Washington Heights. “The one thing that New Yorkers of any political persuasion can agree on is that not picking up after your dog is just a rotten thing to do,” said City Council Member Erik Bottcher. “And it’s more than just unpleasant. It can ruin someone’s entire day.” Hearing increased complaints from constituents about dog poop after the pandemic, Bottcher launched a public information campaign about the issue in 2022. He put up advertisements on his Manhattan district’s digital LinkNYC kiosks that said simply: “There is no poop fairy.”

“It’s made me a bit of a celebrity in our local elementary schools,” Bottcher said. “The kids seem to know me as the poop fairy guy.”

The state seems more and more interested in recognizing animal rights, but dogs are ultimately still entities that belong to people – and owning them involves a great deal of personal responsibility. There is no poop fairy.

“Animal issues do not exist in a bubble,” said Alexandra Silver, director of the Mayor’s Office of Animal Welfare. “So when you’re talking about animal welfare, you are inevitably talking about human welfare, and this is very clear when we’re talking about companion animals, when you’re talking about the shelter system for animals, because the reasons that animals are coming in are very much related to reasons affecting humans.”

Sliwa has a whole list of animal-related proposals he wants to implement on the off-chance he gets elected. He wants to create more animal adoption centers in empty Rite-Aid storefronts, implement subsidized pet veterinary care, city-subsidized dog training and eliminate the sales tax on pet food. When it comes to the human versions of these things – prison upgrades, sanctuary city status for human refugees – Sliwa is much more conservative. But on the animal side of things, the Republican nominee sounds a lot like Mamdani, his socialist Democratic rival. When I pointed this out to him, he said that ever since he went to Catholic grade school in Brooklyn, he was inspired by St. Francis of Assisi, “a man of tremendous wealth who discarded all of that to care for animals.”

“Now, some people could say it’s socialistic,” he said. “I think it’s more Unitarian than socialistic, because I view everyone as an equal here in this world that we occupy, that the animals have just as much rights as people do.”