Eric Adams

Behind ‘all-time high’ job growth in NYC, 17K government positions sit vacant

Public sector hiring in New York City is on the rebound after the COVID-19 pandemic. Unions, lawmakers and employees say it’s still way, way too slow.

A Department of Correction recruiter shares hiring info at a job fair on Staten Island in March. Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Signs of the problem crop up in many places. A smaller portion of families in New York City shelters got mental health assessments in the first four months of this fiscal year compared to last year. The chief medical examiner’s office performed fewer autopsies. The time it took the Fire Department to inspect fire alarms rose 28%. The named culprit in each situation, according to a preliminary report on citywide agency performance: staffing shortages.

And amid a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease this summer, Gothamist found that inspections of building cooling towers – where the disease-causing bacteria can grow – have been on the decline, and the number of inspectors is down over the past three years. The city health department has said it would be “wrong” to attribute the current outbreak to the lower headcount. But hiring more water ecologists is part of its stated plan to reduce the risk of future outbreaks.

The New York City government employs hundreds of thousands of civil servants. There are cops and correction officers. Teachers and school cafeteria aides. Social workers and nurses. There are also more obscure roles, like auto mechanics servicing the city’s vehicle fleet, urban park rangers, property tax assessors and specialists who maintain parking meters.

The workforce is massive, but it’s diminished. More than 17,000 full-time positions in city government were vacant as of August. Officially, the city is no longer under a hiring freeze that was implemented to save money in 2023. But for many agencies, a “2-for-1” policy is still in effect in which a vacant position can only be hired once two other employees have left. Across multiple agencies, unfilled vacancies are straining city workers to a breaking point. “For as long as I’ve been in this city, the way that they look at it is ‘vacancies are savings’ and they refuse to see the actual resource drain, the cost of attrition, burnout and things breaking,” said a 20-year veteran city employee of the city’s budget officials. Like other employees interviewed for this story, this city worker was granted anonymity to talk about staffing woes.

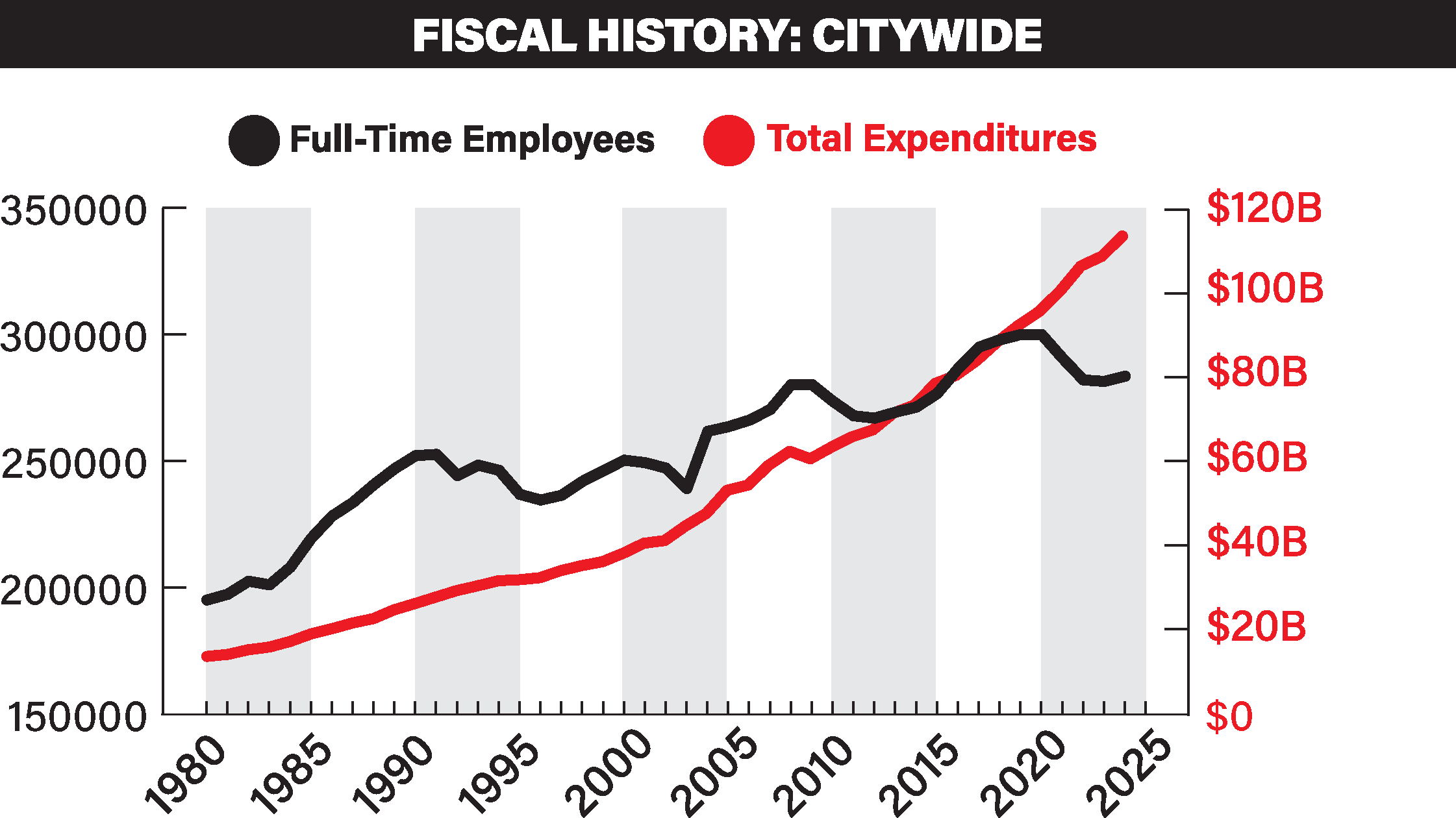

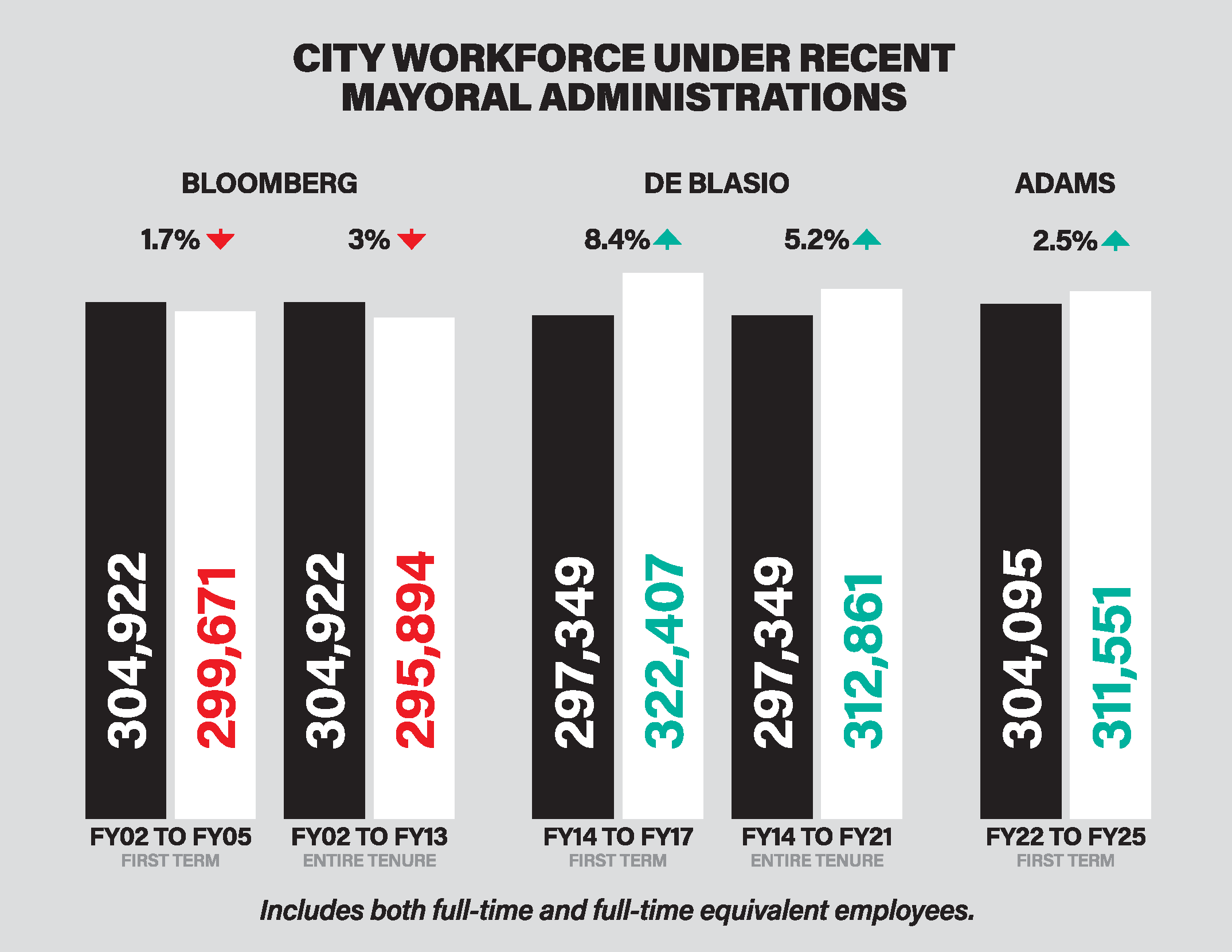

Under then-Mayor Bill de Blasio, the city’s workforce ballooned and peaked at 300,446 full-time workers in fiscal year 2020. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Many government workers retired early or were pushed out because they didn’t want to return to the office, and the private sector promised higher salaries and more flexible work arrangements. In early 2022, when Mayor Eric Adams took office, more than 25,000 full-time positions sat vacant.

Fulfilling a campaign promise, the Adams administration starting slashing more than 7,000 of those vacant positions from the books – a budget necessity it said only became more urgent due to unexpected spending on care and shelter for migrants. In the meantime, the administration said it meant to fill the remaining vacancies, helped by hiring halls held across the city.

Today, the Adams administration points to progress. The job vacancy rate is down from that COVID-era peak of more than 8% to 5.89% – though that reduction is due in part to the simple deletion of thousands of vacant positions from the city budget. Overall headcount is up 3% from when Adams took office. In 2023, the administration agreed to a hybrid work pilot program for a handful of city agencies that has expanded to include tens of thousands of eligible employees. Even Adams’ critics concede that the policy has been successful in retaining some workers after the pandemic, and newly settled contracts with raises for the vast majority of public sector unions have helped too.

But problems persist. The pace of actual hiring can be lethargic – extended by sometimes monthslong waits for approval from the city’s budget office. And in areas where workers have been left doing the same or more work with fewer people, some report a loss of morale that leaves them wondering if the passion that first pulled them into civil service is still strong enough to keep them there.

“One person leaves, someone else has to take their role, and there’s no improvement for them. No title bump, no money bump, just given more stuff to do and the same recognition – or no recognition,” said one employee in the Office of Technology and Innovation. “I think that’s the main cycle here. And I think it’s to the point now where people are leaving because they’re hitting the end of that cycle.”

“I actually enjoy the work that I do. But the sheer volume – it’s not manageable,” said one tax assessor.

So for some, Adams’ frequent championing of private sector job growth feels discordant with the city’s own staffing picture. “I cringe every time I see a post from the mayor’s office like, ‘Most jobs ever,’ and I’m like, ‘Where? Where are they?’” said City Council Member Carmen De La Rosa, who chairs the Committee on Civil Service and Labor. “I think there’s this conflict or fight between being what I think they like to call ‘fiscally responsible’ with city spending, and the trade-off is a workforce that isn’t as robust as it should be.”

“Without us, nothing would move”

The New York City Police Department has more than 3,000 vacancies. The Department of Correction has more than 1,500. The medical examiner’s office is down 16 medical examiners from its budgeted 36. Henry Garrido, executive director of District Council 37, the city’s largest public sector union, said the city’s current vacancies account for more than 8,000 positions that would be represented by his union. That includes school aides, maintenance workers, gardeners and park rangers. Joseph Colangelo, president of the SEIU Local 246 representing auto workers, is down to about 1,300 members from around 1,500 during the de Blasio administration. “We’re not visible to the public,” Colangelo said. “But we are critical to how the city operates. … Without us, nothing would move.”

Unions, of course, have a lot to gain from higher membership. But they’re not the only ones raising alarms about staffing shortages. In their own more subtle way, even agency leaders acknowledge that they don’t always have the resources they need.

NYPD Commissioner Jessica Tisch testified to the City Council in March that 911 operator staffing levels are “significantly down” from when she oversaw the bureau during her earlier tour at the agency during the de Blasio administration. Tisch, who was previously Department of Sanitation commissioner, also said her old department didn’t have enough staff to handle street vending enforcement on its own, though a spokesperson for the department called that assessment out of date and said current staffing levels were sufficient.

While some agencies report bright spots and optimism about filling vacancies – hiring is outpacing departures at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, for example – problem areas remain. There is a 27% vacancy rate in the department’s mental health and hygiene division, including roles like clinical and social workers, acting Commissioner Michelle Morse said in March. The department said that vacancy rate hasn’t changed significantly in the months since.

The department reported that it has not been able to meet its goal of inspecting every registered cooling tower for Legionella bacteria annually – inspections that supplement much more frequent sampling required of building owners – because they’ve been short-staffed. Since the recent Legionnaires’ disease cluster began, the department has brought on three new employees and has seven more starting soon to help fill 12 vacancies for water ecologists. Of the two sites where Legionella was recently found, the department said one, Harlem Hospital, had been inspected within the year, and the other, a construction site, was only registered on July 31.

“The burnout is very real”

Unions and some lawmakers have drawn attention to what they said was understaffing in revenue-generating roles – where staffing up should be a no-brainer, even for budget hawks.

“If you’re not collecting the right amount from each individual homeowner and you have a budget which needs a certain amount of money, you could be missing out on the revenue that could be funding other things for the city,” one city assessor said. “Money is being left on the table.”

The union representing city tax assessors testified at a March council hearing that more experienced and supervisory level assessors were needed to evaluate districts that are undergoing more complex physical changes, like new construction. “As time passes, the workload is not decreasing, it is increasing, yet the staff (especially experienced staff) keeps shrinking,” Candice Ficalora, president of Local 1757, said in written testimony.

The assessor said their own workload has them looking to the private sector. “It’s very demoralizing,” the assessor said. “You want to stay in city service, but there’s zero appeal at this point.”

In statements, both the Department of Finance and the Tax Commission said they’re able to carry out their work. “Under the Adams administration, we will continue to fill these positions with qualified candidates as quickly as possible, and no matter what, we always carry out our critical work to ensure the accuracy and fairness of the city’s tax administration,” a Department of Finance spokesperson said.

A Tax Commission spokesperson rejected the suggestion that understaffing in the assessor role could negatively impact the city’s tax revenue. “Being that the total number of assessors at The Tax Commission has not impacted the agency’s ability to meet its charter-mandated mission, the Tax Commission disagrees with the premise of the question,” they wrote in an email.

But in a presentation that the Tax Commission made at New York Law School in January, the commission acknowledged that it was working with reduced resources, saying “virtually all areas of Tax Commission operations were impacted” by fewer staffers in multiple roles, according to the presentation obtained by City & State.

One 20-year veteran civil servant said challenging workloads and slow hiring weren’t problems limited to this administration. But in prior administrations, it seemed easier to actually get people hired. “To be fair, this happened before Adams. There were things we were trying to do to address it. But people are doing the work of three people,” the employee said. “The burnout is very real.”

The black box

For many people, civil service isn’t a hard sell. They’re eager to work for the city. They apply to an agency, and the agency is equally eager to hire them. Theoretically, it should be a simple equation for the city to tick off one of its 17,942 vacancies. In reality, it can take months to actually do so.

That was the case for one former employee at the Department of Correction, who received a tentative offer from the agency within weeks of their final interview. The employee accepted the position. But to make it official, the city’s Office of Management and Budget needed to sign off on it. It was three months before they gave the go-ahead. “I didn’t know if I was going to have the job or not,” the employee said. “OMB is kind of a black box.”

Though the Department of Correction had warned that the process could take a couple months, they could provide no specific timeline. “Anecdotally, I’ve heard colleagues of mine who have been approved in two weeks. I’ve heard of other folks who have been approved in eight months,” the employee said.

Staffing problems aren’t new to city government, nor are they limited to the Adams administration. Public sector employment across the country has struggled to bounce back as fast as the private sector post-pandemic. The state of New York went through its own pandemic staffing crisis, though its overall headcount is reaching pre-pandemic levels now. Even today, the New York City Council has a 22% vacancy rate, according to a record of OMB headcount data maintained by the New York City Comptroller’s Office.

But there is a feeling among some inside city government that hiring is more difficult than it needs to be in New York City. It’s one thing to fight for a new funding line to hire more workers than a department is currently budgeted for – it’s another to fight for the ability to hire someone in a position that’s already vacant.

Some think the budget office has been more involved than usual lately. “I’ve heard time and time again that the logjam is within OMB, that they are holding up candidates,” said City Council Member Julie Menin, who under de Blasio served as commissioner of both the Department of Consumer Affairs and commissioner of Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, and led the city’s 2020 U.S. census efforts. “Then we lose that individual, the individual finds another job – understandably so – and the position remains vacant.”

Both Menin and Garrido said they’ve even heard of the budget office wanting to interview candidates for jobs at other agencies themselves. City Hall said the Office of Management and Budget’s goal is ensuring that salaries are aligned with collective bargaining agreements, and that the only occasion on which they would participate in an interview is when a candidate is applying for a job in that department. A spokesperson for City Hall did not comment on concerns shared that the budget office’s approvals have become more difficult under this administration, or clarify whether OMB has a target for approving positions within a certain time period.

“When Mayor Adams came into office, the city’s workforce had a higher-than-average vacancy rate and was still reeling from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic,” mayoral spokesperson Liz Garcia wrote in an email. “Since then, the Adams administration has recovered New York City’s economy and tourism industries, driven down crime, navigated the city through an $8 billion migrant crisis, and built, preserved, and planned for an unprecedented amount of housing across our city – all while reducing the vacancy rate and increasing the headcount by over 3,000 people.”

Although Adams’ vacancy reductions prompted an outcry among his critics, some budget experts agreed that the city’s headcount didn’t need to be as high as it was when Adams came into office and more than 25,000 positions sat vacant. “Adams was totally right to do it,” Citizens Budget Commission President Andrew Rein said of Adams eliminating thousands of open positions. “Why should we be carrying all these vacancies?”

Where the administration erred was in cutting too bluntly, Rein said. “The vacancies aren’t where we need them, and our systems aren’t flexible enough to hire good people quickly.”

The case for civil service

For some 300,000 New Yorkers, the allure of civil service can’t be dulled. Call it passion. Or a pension. Or some combination.

“The benefits are pretty good,” said the 20-year veteran employee. “Public service is something that has always interested me. And I’m a person who needs some job stability and security.”

“Nobody calls me on the weekend. And if they did, I would probably not pick up and I don’t think I would face any consequences for that,” said a city employee who works in IT. A tech worker at Amazon, for example, couldn’t necessarily say the same. “Also, you are less likely to get canned in layoffs,” the employee said.

Some also hope that there may soon be a new administration. Adams is running for reelection, but he’s doing so on a difficult path as an independent candidate. His opponents (for now) include Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani, who leads in polls, fellow independent candidate and ex-Gov. Andrew Cuomo, and Republican Curtis Sliwa. Several workers said they’re hopeful about a potential Mamdani administration in particular, though none of the mayoral candidates have promoted any detailed plan for how they’d approach hiring and retention of the city’s workforce at large.

“While the Adams administration hollowed out our agencies and left residents behind, Zohran Mamdani will fully fund our city agencies and build a government that delivers,” Mamdani spokesperson Dora Pekec said.

And spokesperson Rich Azzopardi said Cuomo would review the city’s bureaucracy “to determine the greatest needs and the best allocation of resources.”

Hopeful or not, don’t expect those workers to fall in line with a mayor who doesn’t work for them. “Full disclosure, I voted for (Mamdani), I support his candidacy,” the tech employee said. “But at the same time, I realize as a union member, I’m going to have to negotiate against him should he become mayor. So I support him, but I’m willing to fight him later.”