Politics

The inside story of the fight against Hector LaSalle

How a socialist organizer, public defenders, union leaders and abortion rights activists worked together to oppose Gov. Kathy Hochul’s chief judge nominee.

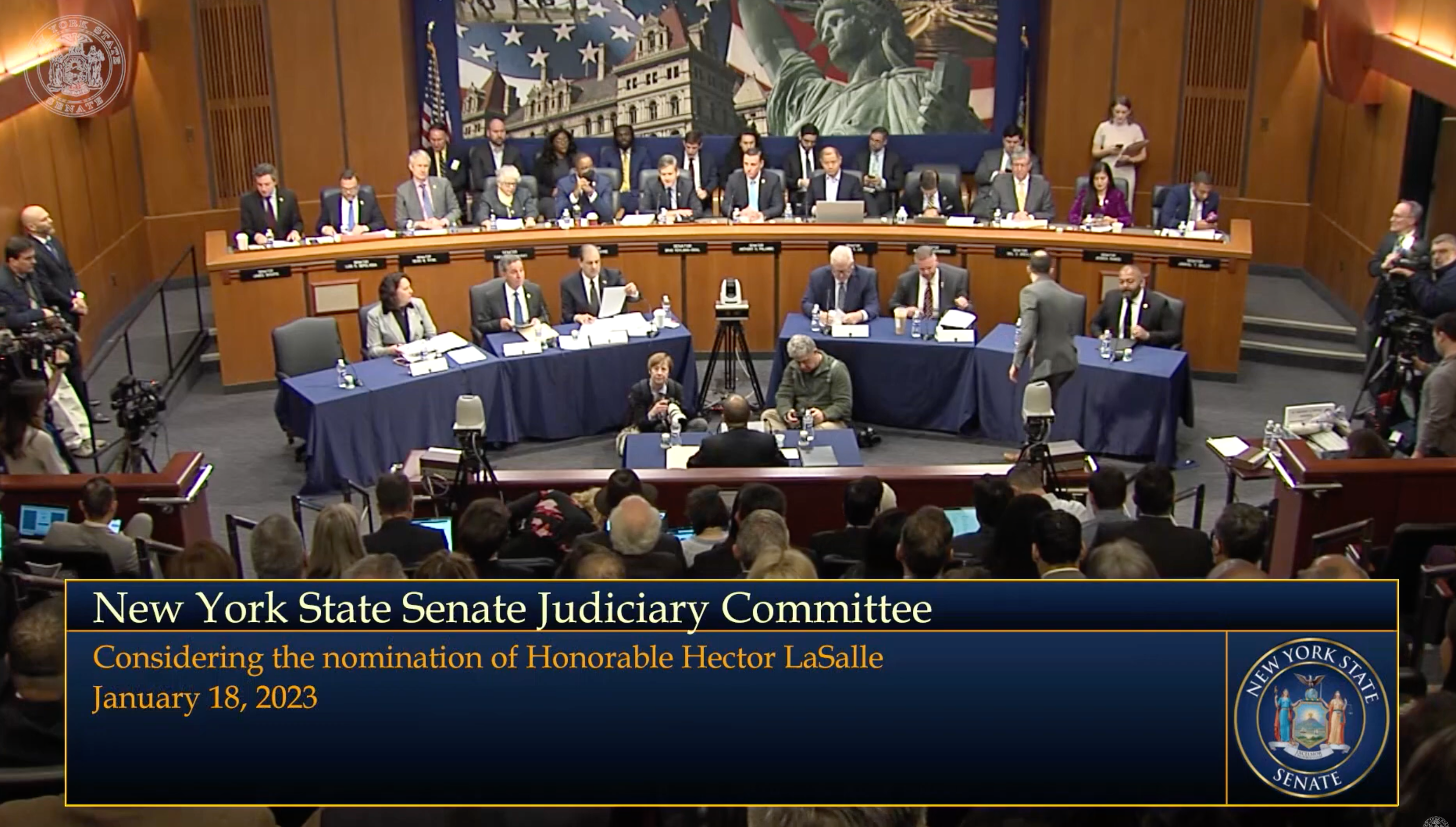

Screenshot of Hector LaSalle at the Judiciary Committee Hearing New York state Senate via YouTube

On Dec. 22, Gov. Kathy Hochul nominated Hector LaSalle to be chief judge of the state Court of Appeals, New York’s highest court. Within days, unions, reproductive rights groups and a number of state senators had announced their opposition to the nomination. If confirmed, LaSalle would have made history as the first Latino chief judge. Instead, he made history as the first Court of Appeals nominee to be rejected by the state Senate.

The opposition to LaSalle’s nomination did not spring up out of nowhere. It was the culmination of more than a year of diligent organizing by an informal group of attorneys, academics and criminal justice reform advocates. The exact size of the group varied over time, from about eight people to more than 20, and it primarily coordinated its activities through Zoom calls and shared Google Docs. The group had no official name or institutional affiliation – and with one exception, all of its members were volunteers with unrelated day jobs – but it helped steer an advocacy campaign that ultimately attracted support from hundreds of progressive groups, unions, reproductive rights organizations and politicians.

This inside account of that campaign was based on interviews with more than a dozen people, including core members of the organizing group, politicians who were in frequent contact with the group and the group’s allies in organized labor.

A first attempt

The organizing group got its start in May 2021, after then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo nominated Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas to a vacant seat on the Court of Appeals.

The nomination alarmed a number of public defenders and criminal justice reformers, who were concerned about Singas’ hostility to the state’s recently enacted bail and discovery reform laws. A small group of Singas critics started looking for ways to stop the nomination. They were passionate but had little experience with Albany politics.

This early iteration of the group included socialist organizer Peter Martin, New York University School of Law professor Noah Rosenblum, and public defenders Alice Fontier and Liz Skeen.

“I cannot stress enough how completely amateurish it was,” Rosenblum told City & State. “All of us had full-time jobs doing other things. We were just really worried about the direction of the courts.”

After meeting on Zoom to discuss their options, the group created a website, StopSingas.com, and published an open letter asking the state Senate to reject her. At the time, the idea of the state Senate actually turning down the governor’s pick for the Court of Appeals was almost unthinkable.

“The norm at that point was for nominees to sail through without significant scrutiny, and no gubernatorial nominee had faced significant opposition, never mind rejection,” Rosenblum said.

As a result of the Stop Singas campaign, 10 progressive Democratic senators voted against the nomination. Though the inexperienced organizers didn’t succeed in stopping Singas, they came away from the campaign with an appreciation of the behind-the-scenes politics that shape judicial nominations. They also developed connections with a number of Democratic senators who were interested in changing the court, including Julia Salazar, Jabari Brisport, Gustavo Rivera, Jessica Ramos, Alessandra Biaggi and Zellnor Myrie.

The organizing group gained two particularly powerful state Senate allies in Judiciary Committee Chair Brad Hoylman-Sigal and state Senate Deputy Majority Leader Michael Gianaris. Each had initially earned organizers’ ire – Gianaris for supporting Singas’ nomination and Hoylman-Sigal for declining to issue a public statement opposing her nomination (despite ultimately voting against her). However, the Singas nomination indicated a willingness to take the Court of Appeals nomination process more seriously in the future.

“There was, I think, a bigger recognition that attention would be paid the next time an appointment came open,” Fontier said. “And then it just so happened that it happened far more quickly than any of us anticipated with Judge (Janet) DiFiore stepping down.”

Another chance

In July 2022, Court of Appeals Chief Judge Janet DiFiore suddenly announced her retirement, more than three years earlier than her term would’ve expired. The organizing group saw an opportunity to move the Court of Appeals in a new direction.

A lot had changed in the year between Singas’ confirmation and DiFiore’s resignation.

A series of controversial decisions had made the issue of the court’s ideology more salient for many liberals. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization as well as New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen gutted abortion rights and New York’s concealed carry laws, respectively. In Harkenrider v. Hochul, the Court of Appeals threw out the state’s new congressional and state Senate district maps, putting the 2022 electoral calendar into disarray and potentially contributing to Republican victories in New York’s House races.

“I wish I could credit it to our genius advocacy, but let’s be honest, it’s because the federal and then the state court both went stark raving mad,” said one group member, a practicing attorney who spoke on condition of anonymity. “When you’ve got the Supreme Court handing out opinions saying, ‘Oh, well, let’s undo every constitutional right since 1963,’ and then you’ve got the Court of Appeals saying, ‘We’re going to give the control over districts to an upstate Republican judge,’ you know, that’s going to get politicians’ attention.”

Martin, meanwhile, had joined the nonprofit Center for Community Alternatives as director of judicial accountability, allowing him to work full time on the courts – including Court of Appeals nominations.

In August, Martin circulated a letter calling on Hochul to nominate someone who reflected the state’s progressive values and who was not a former prosecutor. As City & State reported at the time, more than 100 progressive groups signed the letter – including the United Auto Workers Region 9A, which represents many public defenders, and the Working Families Party.

Martin and other members of the organizing group also worked closely with Gianaris and Hoylman-Sigal to draft a separate letter for individual senators to sign, which hit on many of the same themes as the letter from the coalition of progressive groups. That letter was addressed to the Commission on Judicial Nomination, the body charged with interviewing applicants for the chief judge position and drawing up a shortlist of seven candidates for the governor to choose from. In the end, 20 state senators signed that letter.

At the same time, organized labor took an interest in the Court of Appeals vacancy. Martin was in touch with an attorney at a powerful union, who drafted a letter to the Commission on Judicial Nomination. That letter, the existence of which has not previously been reported, was signed in late October by representatives of 10 unions, including some of the state’s largest.

Finalists emerge

On the day before Thanksgiving, the Commission on Judicial Nomination released its shortlist of seven candidates: acting Chief Judge Anthony Cannataro, Presiding Justice Hector LaSalle, Associate Justice Jeffrey Oing, Deputy Chief Administrative Judge for Justice Initiatives Edwina Richardson-Mendelson, Yale Law School professor Abbe Gluck, Albany Law School President and Dean Alicia Ouellette and Legal Aid Society attorney Corey Stoughton. The governor had 30 days to select a nominee.

Members of the organizing group got to work, digging through candidates’ records and creating shared Google Docs to keep track of their findings. They also reached out to senators’ offices to share the results of their analysis.

The anonymous attorney in the group searched legal case databases for all of LaSalle’s decisions and read every one.

“I don’t know anyone else who’s read all 5,000 of his cases, but I have,” he said. “I have read everything this man has ever written in a judicial capacity. I went through 100 opinions a day, every day after work. Thank God they’re only a paragraph long.”

After reviewing the candidates’ records, the organizing group quickly came to a consensus opinion that Stoughton, Richardson-Mendelson and Gluck would be good choices for chief judge, while LaSalle, Oing and Cannataro would be unacceptable choices. (The group took no position on Ouellette.)

The week after the shortlist was released, Martin and other organizers began meeting with as many Democratic senators’ offices as possible to share their findings. They ultimately met with a majority of the Democratic conference.

By mid-December, it seemed to the group of organizers that LaSalle, Gluck and Richardson-Mendelson had emerged as the most likely candidates for the nomination.

“At that point, our task was very clear: to make sure Hochul didn’t pick Hector LaSalle and instead picked one of the other two likely candidates,” Martin said. “We started to make the case publicly against him even before he was nominated.”

While reviewing all of LaSalle’s decisions, the organizers found a few that stood out as controversial. In Evergreen Association Inc. v. Schneiderman, LaSalle joined a decision that narrowed the state attorney general’s subpoena of a network of anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers. In Cablevision Systems Corp. v. Communications Workers of America District 1, he joined a ruling that allowed a defamation lawsuit against two union officials to go forward, despite a state law meant to prevent union leaders from being held liable for the activities of their unions.

“When we realized that there were decisions he had joined or authored that were anti-labor or anti-women’s rights, it was at that point that we started reaching out to a broader coalition of organizations,” according to one attorney involved in the organizing.

Martin contacted a dozen or so unions to make sure they were aware of the Cablevision decision and connected with staffers at reproductive rights organizations who were concerned about LaSalle’s ruling in Evergreen. Meanwhile, Rosenblum and David Siffert, a member of the group and the director of research and projects at the NYU School of Law’s Center on Civil Justice, recruited 46 law professors to publish an open letter criticizing LaSalle’s record, including his decisions in Evergreen and Cablevision.

“The thing about that letter was it both captured three wrongly decided decisions, but it also did a good job of showing the substantive breadth of the ways that LaSalle thought about things wrong,” Siffert said. “So it was criminal and it was labor and it was (reproductive rights). It was both right on the law and accurate, but also responsive to the political issues of the moment.”

Before the nomination was announced, many people tried to warn the governor and her team not to nominate LaSalle.

“I told them that I did not think it was a good idea,” said James Mahoney, president of the New York State Iron Workers District Council, adding that multiple high-ranking labor officials warned the governor that she would get a “bad reaction” if she picked LaSalle.

“Our reaction to our nomination should have been no surprise to anyone, and that was communicated ahead of time,” Gianaris told City & State. “The opinion of many senators about the pick and the choices before the governor were made clear.”

Hoylman-Sigal said he also tried to warn the governor in advance – in the hopes of avoiding a nasty confirmation fight in the state Senate.

“I was trying to be helpful,” he said. “I’m a supporter of the governor. I campaigned hard for her. I didn’t want there to be an unforced error or for somebody to say, ‘I wish you would have told us sooner.’”

But he worried the governor might not heed his warnings. “I got a sinking suspicion she was going to do what she wanted to do,” he said.

Senators buy in

On Dec. 22, Hochul announced the nomination of LaSalle to be chief judge. A press release from the governor’s office quoted dozens of political groups and elected officials – though tellingly, relatively few state senators – who praised LaSalle as a “brilliant, fair-minded jurist” with “a wealth of experience.”

On a Zoom call, members of the organizing group expressed a mix of despair and determination.

“I think certainly some people were disheartened and others were like, OK, I guess we have to work harder,” Fontier said. “Ultimately, you know, nobody gave up.”

To have a shot of stopping the nomination, organizers needed as many senators as possible to declare their public opposition to LaSalle’s nomination. Martin began making calls.

Within hours of the nomination being announced, the three DSA senators – Kristen Gonzalez, Julia Salazar and Jabari Brisport – announced their opposition to LaSalle. They were quickly followed by state Sens. Gustavo Rivera, Samra Brouk, Robert Jackson and Michelle Hinchey. The next day, state Sens. Rachel May, Cordell Cleare and Lea Webb also declared their opposition, bringing the number of senators publicly opposed to the nomination to 10.

As chair of the Judiciary Committee, Hoylman-Sigal did not want to comment publicly on the nomination before holding a hearing. But he praised his colleagues who did speak out.

“When members are willing to take a public stance about such an important issue, it says a lot about how strongly they thought about the nomination,” Hoylman-Sigal said. “It was courageous, if you ask me, on their part. Even though I chose not to do it, I understand their motivation.”

Organized labor also came out hard against LaSalle. The New York State AFL-CIO expressed its concerns about the nomination, while CWA, 32BJ SEIU as well as the carpenters and ironworkers unions each released statements urging senators to vote against LaSalle.

“This is the first time that labor had the ability to make a difference in a Court of Appeals nomination,” Mahoney said. “You’ve got to remember that during the Cuomo administration, we may not have liked somebody, but I don’t think that labor had the ability to change the direction that the appointment was going.”

On Dec. 29, Gianaris – the second-most-powerful Democrat in the state Senate – said in a statement that he would vote not to confirm LaSalle, becoming the 11th senator to oppose the nomination. This was a turning point.

LaSalle needed 32 votes to be confirmed, and there were only 42 Democrats in the Senate. If at least 11 Democrats voted against the nomination, then LaSalle could only be confirmed with the help of Republicans.

Before the end of the year, three more Democrats – state Sens. Jessica Ramos, John Liu and Shelley Mayer – declared their opposition to LaSalle, bringing the opposition to 14 state senators. And that was just the public count. Even more senators, including members of the Judiciary Committee, were saying privately that they planned to vote against LaSalle.

With so much opposition to LaSalle within the Democratic conference, the writing was on the wall.

“Once 14 senators came out against, I was never afraid that (state Senate Majority Leader) Andrea Stewart-Cousins would narrowly lose a floor vote,” Martin said. “That’s just not how Senate politics works.”

After the Judiciary Committee scheduled a hearing on LaSalle’s nomination, even more outside groups joined the coalition against LaSalle. On Jan. 8, more than 50 reproductive rights groups sent a letter to Hochul urging the state Senate to reject the nomination. Five days later, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund announced its opposition to LaSalle.

“When the NAACP Legal Defense Fund – one of the most respected civil rights organizations in the country – made a public statement, I think that was a defining moment for the opposition,” Hoylman-Sigal said.

On Jan. 18, Hoylman-Sigal’s Judiciary Committee held a five-hour hearing on the nomination and voted 10-9 to reject the nomination. Most of LaSalle’s support on the committee came from Republicans; 10 out of the 13 Democrats on the committee voted against the nomination.

The LaSalle saga dragged on for another month. Despite the committee vote, the governor insisted that the state constitution required a full floor vote on the nomination, and Republican state Sen. Anthony Palumbo filed a lawsuit to force a floor vote. During the vote on Feb. 15, the Senate voted 39-20 to reject the nomination, with only one of the Senate’s 42 Democrats voting for Hochul’s nominee.

Everyone who spoke to City & State about the LaSalle opposition campaign – public defender, union leader and politician alike – agreed that the campaign likely would not have succeeded without the full-throated support of organized labor.

“Ultimately that’s why we were successful, because labor got into the fight in a way that in this political climate, we really couldn’t,” one public defender who participated in the Zoom meetings said. “We weren’t going to win this fight by saying he’s anti-criminal defendant. We won because he was anti-labor.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of Democrats who voted in favor of LaSalle's confirmation during the Senate floor vote.