Criminal Justice

A (not so) brief guide to New York’s bail reform evolution

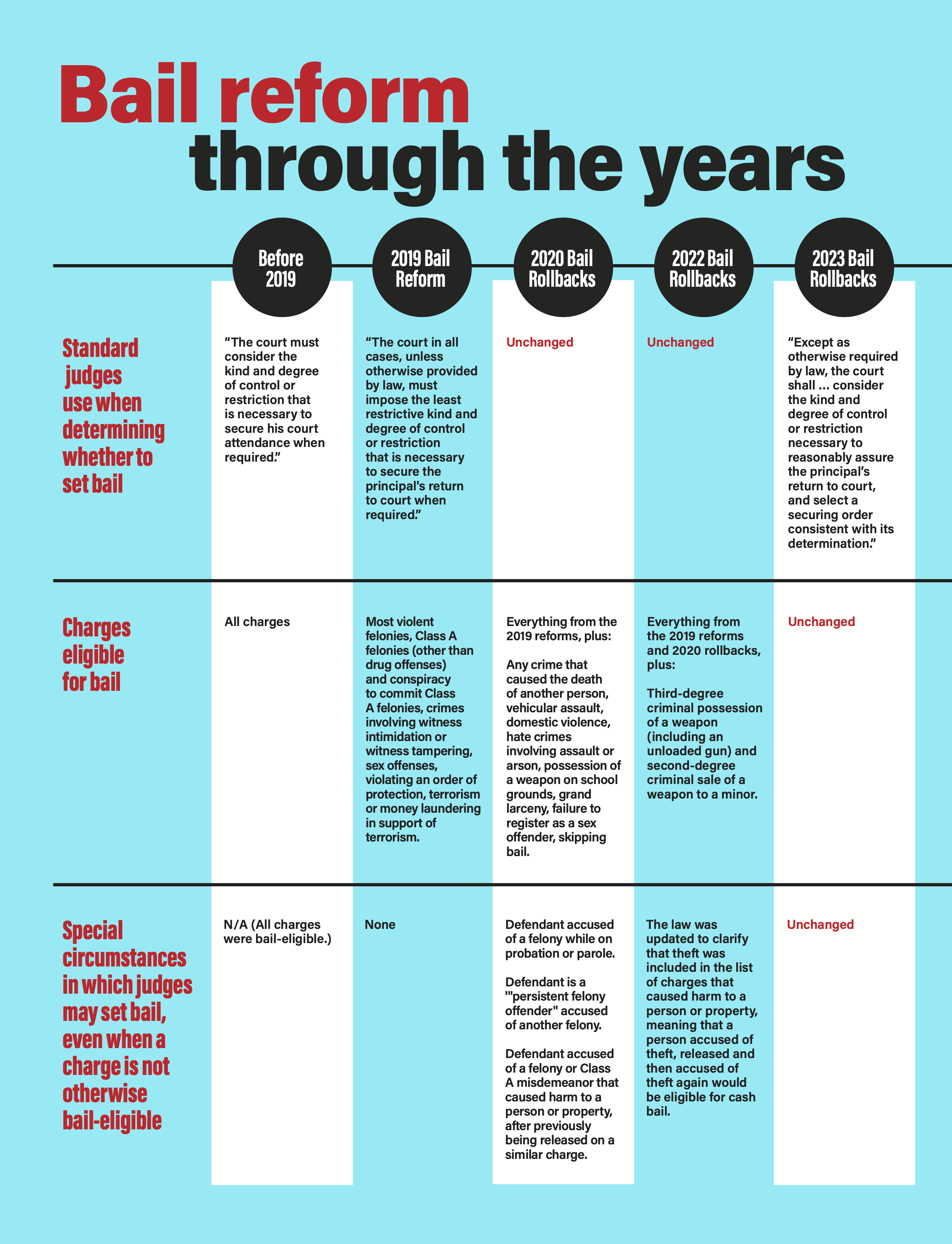

Highly technical modifications to the state’s criminal procedure law have become a symbol of “soft on crime” policies and derailed negotiations over multiple budgets.

The fundamental purpose of bail is to ensure that someone accused of a crime does not skip town before their trial in an attempt to evade justice. boonchai wedmakawand, Moment, Getty Images

Since 2018, the laws concerning New York state’s bail and discovery procedures have been modified four times – most recently in this year’s state budget.

The specific changes to the laws have been difficult for people unfamiliar with the legal system to understand. In some ways, the actual modifications to the state’s criminal procedure law are beside the point. The term “bail reform,” which was originally used to refer to a package of changes to the bail law passed as part of the 2019 state budget, has since become a catch-all term for “soft on crime” policies – blamed for everything from a rise in shootings during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic to a reported rise in shoplifting from chain pharmacies. The backlash has led the governor and state Legislature to negotiate three “rollbacks” to the bail reform law – in 2020, 2022 and 2023.

Most media coverage of “bail reform” has focused on anecdotal evidence of alleged “repeat offenders:” people who were initially arrested on suspicion of a crime, arraigned before a judge and instructed to return for a later court date – only to be arrested again for another alleged crime before their court date. Critics of bail reform have derisively referred to this as “catch and release.”

But it’s important to remember that this policy did not actually start with the 2019 bail reforms. The idea that people should be released before trial and only locked up as punishment after they have been convicted of a crime is actually a fundamental aspect of the American justice system. Holding people in pretrial detention has traditionally been the exception, not the rule.

To truly grasp the significance of bail reform, and its subsequent rollbacks, it’s necessary to understand what “bail” actually means.

The purpose of bail

“The way our system works is you’re accused of something, and then you go to trial,” explained Eli Northrup, policy director of the criminal defense practice at Bronx Defenders. “If you’re found guilty, that’s when you’re punished. But what bail does, particularly unaffordable cash bail, is it punishes people prior to any finding of guilt.”

The fundamental purpose of bail is to ensure that someone accused of a crime does not skip town before their trial in an attempt to evade justice. The central idea behind cash bail is to require defendants who promise to return to court to put their money where their mouth is.

If a judge believes that someone is unlikely to return to court, they can require them to post cash bail. This essentially requires the defendant to loan the court a large amount of money, which is later returned to them if they show up to future court dates as promised. (Of course, many defendants and their families do go into debt to post bail after taking out speedy loans to cover the costs.) It’s supposed to make defendants less likely to try to flee from justice and ignore their court dates, since doing so would mean that they would not get the money back.

New York state law has always made this clear. When the bail law was codified in 1971, the Legislature rejected a provision that would have allowed judges to lock up people whom they considered “dangerous” to public safety. Instead, the Legislature wrote the law to explicitly say that judges could only set cash bail in order to ensure that defendants return to court. Even as other states have altered their bail laws to allow judges to jail people for other reasons before trial, New York has always limited the purpose of bail to incentivizing defendants to show up to their future court dates.

The bail law before bail reform

Well before the 2019 bail reform laws were even proposed, New York’s criminal procedure law stated that the “court must, by a securing order, either release (the defendant) on his own recognizance, fix bail or commit him to the custody of the Sheriff.”

This law specifies the options the judges have during an arraignment, a court hearing in which someone is formally accused of a crime. The three options are releasing someone on their own recognizance, setting cash bail or remanding someone directly to Rikers. Releasing someone “on his own recognizance” is a legal term that just means releasing someone after they promise to show up to future court dates. (Former President Donald Trump was arraigned and released on his own recognizance earlier this month, for example.) Setting cash bail means releasing the defendant after they post a certain amount of money in a bond and sending them to Rikers if they either will not or cannot do so. Remanding someone directly to custody means sending someone directly to Rikers because the judge has determined that no amount of cash bail could be set that would ensure their return to court.

When deciding whether to set cash bail, judges were required to “consider the kind and degree of control or restriction that is necessary to secure his court attendance when required.” In other words, judges were only allowed to impose conditions (such as cash bail) in order to ensure that the defendant would return for later court dates. When considering whether cash bail was necessary, judges were allowed to consider a number of factors: the defendant’s character and reputation, employment and financial resources, family and community ties, criminal record, history of showing up to court and possession of a firearm.

If the defendant were released – either because the judge did not set bail or because the defendant posted the necessary amount of cash bail – then the judge was instructed to warn the defendant that “the release is conditional and that the court may revoke the order of release and commit the principal to the custody of the sheriff … if he commits a subsequent felony while at liberty.”

Violating the spirit of the law

The criminal procedure law allowed judges to set cash bail of any amount for any offense, so long as they believed that doing so was necessary to ensure that a defendant wouldn’t skip out on their future court date. In practice, judges set cash bail all the time and it’s doubtful whether doing so was truly necessary. Studies have shown that about 90% of defendants who are released before trial will show up to subsequent court hearings, whether or not they have to post any monetary bail. That suggests that in the vast majority of cases, cash bail was not actually necessary to secure a defendant’s court attendance, and it’s hard to imagine that judges truly believed it was. Rather, judges were using cash bail as a way to keep people in pretrial detention who they thought might pose a threat to the community – even though doing so actually violated state law.

When a defendant could not afford to pay cash bail, they were detained in Rikers until their trial date. The end result was thousands of poor people locked up at Rikers despite only being accused, not convicted, of a crime. Under the logic of the bail law, they were technically only being detained because a judge had determined that they might flee the state if they were released. In reality, the only reason that they were in jail was because they were poor. “Bail should only be used to make sure that someone is there for their trial,” Northrup said. “What it’s turned into is a system where you are effectively presumed guilty if you cannot afford bail.”

This perversion of the cash bail system threw into sharp relief the inequities of the justice system. Rich people could literally buy their freedom by posting bail, while poor people accused of the exact same crimes would languish in Rikers – the average time spent in the jails is 115 days – solely because they could not afford bail. This made the cash bail system a popular target for reform among both progressives and moderate Democrats.

In 2018, the Assembly passed a bail reform bill sponsored by Democratic Assembly Member Latrice Walker, though the bill died in the state Senate, which at the time was controlled by Republicans. The bill eliminated cash bail for most offenses. But the bill’s prospects improved once Democrats retook control of the state Senate later that year. In 2019, former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, state Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie agreed to include bail reform in that year’s budget. At the time, many Democrats in the Legislature regarded it as a relatively moderate and common-sense policy.

2019 Bail Reform

The original reforms eliminated cash bail for many nonviolent and low-level offenses. For other offenses, the law now required judges to be explicit about flight risk for defendants for whom they set bail.

After bail reform went into effect, the criminal procedure law was modified to say that the “court shall, in accordance with this title, by a securing order release the principal on the principal's own recognizance, release the principal under non-monetary conditions, or, where authorized, fix bail or commit the principal to the custody of the sheriff.” This gave judges another option at arraignment. Rather than releasing a defendant, setting cash bail or remanding them directly to jail, judges could now impose non-monetary conditions like requiring electronic monitoring of defendants.

The law also made clear that releasing defendants should always be the default option: “In all such cases, except where another type of securing order is shown to be required by law, the court shall release the principal pending trial on the principal's own recognizance, unless it is demonstrated and the court makes an individualized determination that the principal poses a risk of flight to avoid prosecution. If such a finding is made, the court must select the least restrictive alternative and condition or conditions that will reasonably assure the principal's return to court. The court shall explain its choice of release, release with conditions, bail or remand on the record or in writing.”

The upshot was that judges could only impose cash bail (or non-monetary conditions or remanding directly to jail) if they find that it is specifically necessary to ensure that the specific defendant in front of them returned for future court dates. This wasn’t really a change in the law so much as a clarification. Even before bail reform was enacted, judges were only supposed to set cash bail when it was necessary to ensure that a defendant returned for future court dates. The new language just made it crystal clear for judges: Don’t set cash bail unless you can explain in writing why it is necessary to ensure that this specific defendant won’t flee from justice.

The law went on to say that for most low-level offenses, judges could not set any cash bail (though they could still impose non-monetary conditions if deemed it necessary to ensure a defendant’s return to court). Specifically, the law states that “the court shall release the principal pending trial on the principal's own recognizance, unless the court finds on the record or in writing that release on the principal's own recognizance will not reasonably assure the principal's return to court. In such instances, the court shall release the principal under non-monetary conditions, selecting the least restrictive alternative and conditions that will reasonably assure the principal's return to court.”

However, judges were allowed to set cash bail when the defendant was charged with a more serious “qualifying offense” and the judge believed that cash bail was necessary to ensure the defendant’s return to court. The issue of which crimes should count as bail-eligible “qualifying offenses” later became the subject of considerable debate during both the 2020 and 2022 state budget negotiations. When bail reform was first enacted, “qualifying offenses” included: violent felonies (except for second-degree burglary and second-degree robbery), Class A felonies (except for drug offenses other than drug trafficking) and conspiracy to commit Class A felonies, crimes involving witness intimidation or witness tampering, sex offenses, violating an order of protection, terrorism or money laundering in support of terrorism.

In order to set cash bail for any of those offenses, though, the judge still had to make an individualized determination that bail was necessary to ensure that the defendant would return for their future court date and explain their reasoning. Before setting cash bail, judges were also required to consider the defendant’s “ability to post bail without posing undue hardship, as well as his or her ability to obtain a secured, unsecured, or partially secured bond.”

2020 Rollbacks

Even before the bail reform law went into effect at the start of 2020, prosecutors and law enforcement officials condemned it as a misguided policy that would cause crime to spike. The criticism prompted Cuomo and legislative leaders to revisit the reforms during 2020 budget negotiations. There was particular concern over the idea of “repeat offenders” – people accused of misdemeanors who were released following arraignment, only to later be arrested on suspicion of committing more misdemeanors, arraigned and then released again.

In response, the Legislature agreed to add more than 30 additional misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies to the list of bail-eligible “qualifying offenses,” including: any crime that allegedly caused the death of another person, vehicular assault, strangulation or unlawful imprisonment related to domestic violence, a hate crime involving third-degree assault or third-degree arson, criminal possession of a weapon on school grounds, grand larceny and money laundering (even not in support of terrorism), failure to register as a sex offender, skipping bail or fleeing from custody.

In addition to making specific charges bail-eligible, the 2020 modifications to the bail law also made it easier for judges to set cash bail for so-called “repeat offenders.” A judge could set cash bail for a defendant accused of any felony – even one that would ordinarily not be bail-eligible – if the defendant was classified as a “persistent felony offender,” which meant that they had previously served prison time for felonies on at least two occasions. The same was true of any defendant accused of a felony while out on parole. In addition, judges were allowed to impose cash bail for any defendant who was accused of a felony or Class A misdemeanor that involved “harm to an identifiable person or property,” released after arraignment and then later accused of another felony or Class A misdemeanor involving harm to a person or property.

These changes didn’t make much difference for people accused of violent felony offenses, since those were already bail-eligible. All they really did was make it easier for judges to impose cash bail on people who were accused of nonviolent and lower-level felonies on multiple occasions.

2022 Rollbacks

The 2020 modifications to the bail law did not satisfy conservatives, who continued to blame “bail reform” for all manner of social ills. In the midst of negotiations over the 2022 budget, Gov. Kathy Hochul suddenly dropped a bombshell on the Legislature – she wanted further changes to the state’s bail law. Progressives in the Legislature resisted; Walker, the Assembly member who first sponsored the bail reform bill, even went on a 19-day hunger strike in protest of Hochul’s proposed rollback of bail reform. In the end, though, the governor and legislative leaders agreed to a compromise that made a few more gun-related crimes bail-eligible.

Specifically, the 2022 modifications added third-degree criminal possession of a weapon and second-degree criminal sale of a weapon to a minor to the list of bail-eligible qualifying offenses. It also clarified that theft and property damage counted as crimes involving “harm to an identifiable person or property” (unless “such theft is negligible and does not appear to be in furtherance of other criminal activity”). This was a clear response to a recent flood of tabloid stories about shoplifting. It effectively allowed judges to set cash bail (and therefore, send to Rikers) anyone who had been accused of theft, released and then accused of theft for a second time.

2023 Rollbacks

This year, Hochul proposed radically redefining the state’s bail law, removing both the “least restrictive means” standard and the language specifying that judges may only set cash bail when they believe it is necessary to ensure a defendant’s return to court. This would have effectively reversed the state Legislature’s decision in the 1970s not to add a “dangerousness” standard to the law. Although Stewart-Cousins and Heastie rejected the governor’s proposal, Hochul refused to negotiate a budget until they agreed to further modify the bail law. And Walker went on another hunger strike.

In the end, legislative leaders agreed to remove language requiring judges to impose only the “least restrictive” conditions necessary to ensure a defendant’s return to court. The criminal procedure law now reads: “Except as otherwise required by law, the court shall make an individualized determination as to whether the principal poses a risk of flight to avoid prosecution, consider the kind and degree of control or restriction necessary to reasonably assure the principal’s return to court, and select a securing order consistent with its determination.”

This article was originally published on April 19. It has been updated with details on the bail law modifications included in the 2023 state budget.

NEXT STORY: Attorney General James proposes bill regulating crypto industry