Homelessness

1 in 9 NYC students were homeless last year

A new report from Advocates for Children outlines causes of the 14% increase, including the ongoing migrant crisis.

More than 119,000 New York City public school students were homeless last school year. Image Source/Getty Images

Roughly 1 in 9 public school students in New York City experienced homelessness last school year, according to new data released Wednesday – a staggering all-time high figure spurred forward in large part due to the ongoing arrival of thousands of asylum-seeking families. To put it in perspective, that’s more than enough children to fill Yankee stadium twice over.

Of the over 119,000 students who were homeless during the 2022-23 academic year, 34% spent time living in city shelters, 61% were doubled up with other families, and 5% were unsheltered or living in cars or hotels, according to Advocates for Children of New York’s annual report on New York State Education Department records.That’s a 14% increase from the 2021-22 school year, although that year’s data was taken before the influx of new arrivals began enrolling in the system.

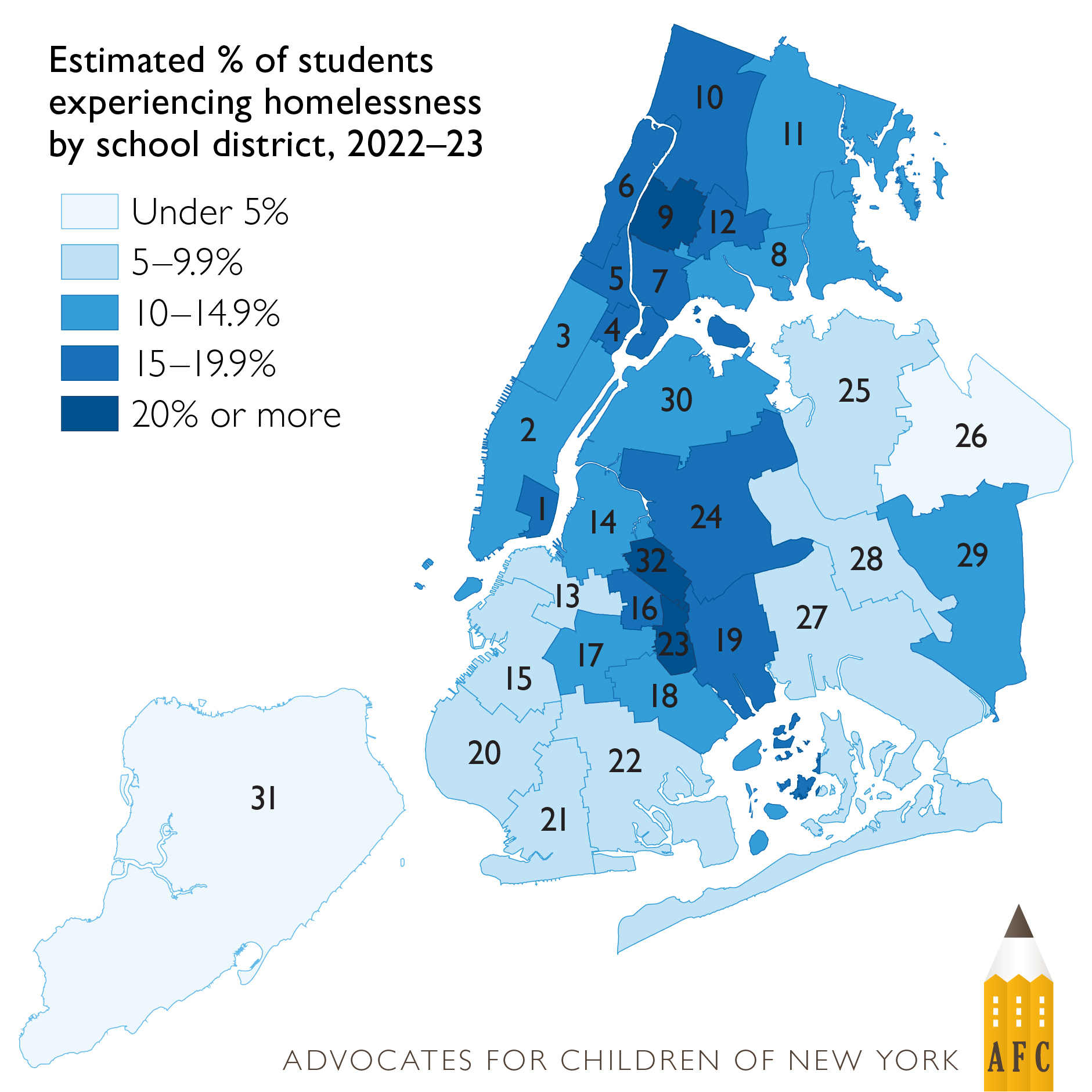

The increase in the number of asylum-seeking families coming to New York City over the past year and a half has gone a long way in increasing public awareness about student homelessness. Still, last school year – while 4% higher than the previous peak tracked in 2017-18 – is the eighth consecutive academic year in which over 100,000 public school students experienced homelessness. Enrollment is still down in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, making the 119,000 figure all the more striking. The areas with the highest concentration of homeless students were the Bronx, East Harlem and Brownsville. That figure has likely only increased this school year. According to a spokesperson for the New York City Education Department,12,500 students living in temporary housing have entered the school system since July 2023.

“Our young people experiencing homelessness are some of our most vulnerable students, and it is our on-going priority to provide them with every support and resource at our disposal,” Deputy Press Secretary Jenna Lyle said in a statement.

All students experiencing homelessness face strenuous challenges to succeeding in school, although those obstacles are especially compounded for families living in shelters. During the 2021-22 school year, New York City students living in shelters dropped out of high school over three times as often as their peers. Just 22% of third through eighth graders received proficient grades on the state language arts exam. A sweeping 72% of these students missed at least one out of every ten school days, making them chronically absent.

These figures can be attributed in part to the fact that even physically getting to school is often a feat for students in shelters. Many end up being assigned to shelters that are far from their current schools, meaning they must choose between embarking on lengthy daily commutes or transferring to another school.

The city’s new policy of limiting shelter stays to 60 days at any one shelter for some asylum-seeking families before they will need to reapply is likely to cause additional disruption, according to the report. While New York City Mayor Eric Adams has vowed that no child’s education will be disrupted, migrant families assigned to a shelter at the isolated Floyd Bennett Field for example would face a punishing commute to school. A spokesperson for the city Department of Education said the system is continuously working to address any issues with transportation to ensure students have the services they need each day to get to and from school.

“While students who move to a new shelter placement have the right to stay in their original school, we know from our experience working with families that this is often a right in name only,” said Jennifer Pringle, director of AFC’s Learners in Temporary Housing project. “Between delays in arranging busing, a shortage of bus drivers, unreasonably long commute times, and other obstacles, parents often feel they have no choice but to uproot their children from schools they love when they move shelters.”

Advocates are urging city leaders to come up with a plan to ensure that the 100 community coordinators hired by the school system to help students and families staying in shelters enroll and engage in schools are able to continue their work after the temporary funds they were hired with run out in less than a year. They are also calling for the city to approve the onboarding of additional staff to aid in this work at other new shelters.

A spokesperson for the city Department of Education acknowledged that the stimulus funding is ending, explaining that this is why in part the city added a new weight to the Fair Student Funding formula to prioritize students living in temporary housing, meaning more money is being allocated to schools with a higher concentration of these students.

“We are grateful for the federal stimulus dollars that have allowed us to establish critical supports for our students and families affected by homelessness, including the shelter-based coordinators that were hired and who have directly supported families within our shelter system,” Lyle said.

This post was updated on Nov. 1 with comment from the city Department of Education.

NEXT STORY: Lawmakers turn up heat on cannabis regulators at hearing